www.dorotheum.com

www.dorotheum.com

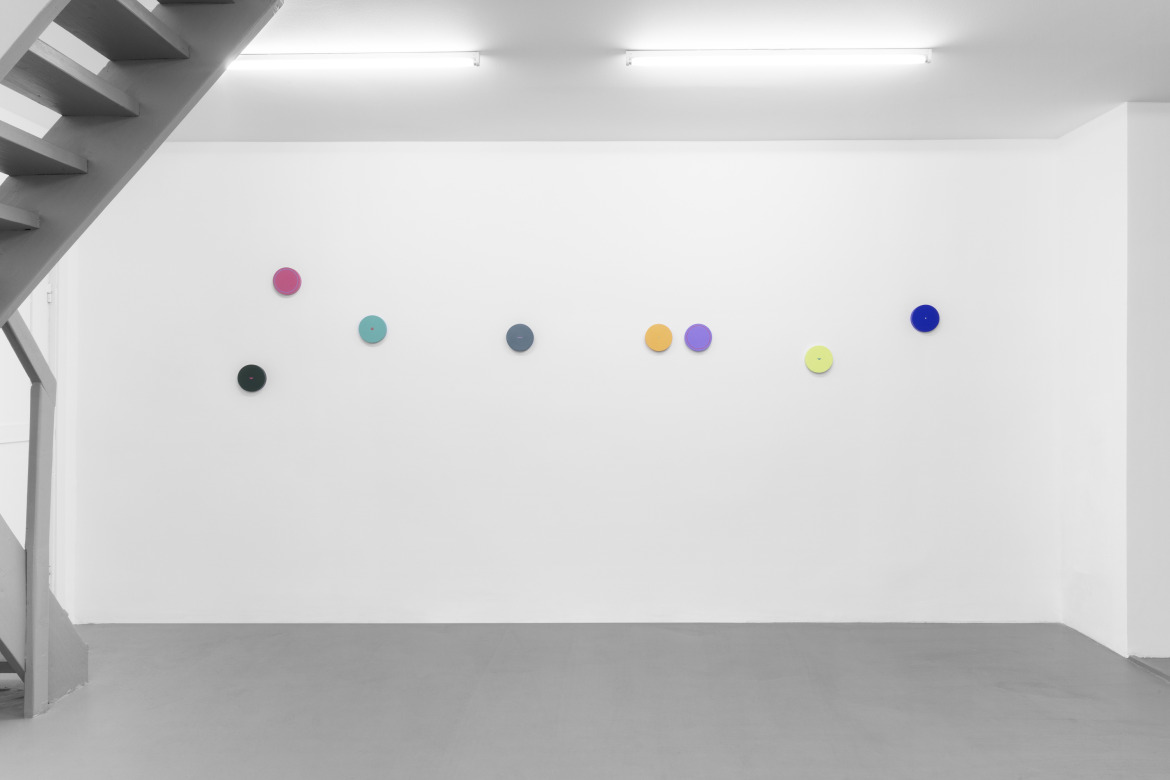

Versatzstücke are parts of stage decorations that can be moved around as desired. In a figurative sense, they refer to reused or rearranged components of a work – be it a thought, a quotation, or an element of a theory – that are used in a new context. In Austrian German, the term is used also for physical objects that function as a pledge, or a security deposit. Versatzstücke is the title of an exhibition at EXILE marking the end of the 1st quarter of the 21st century with works by Kathe Burkhart, Elke Denda, Sigmund Jaray, Tess Jaray, Jobst Meyer, Kazuko Miyamoto, Astrid Proll, W.G. Sebald, and Jiří Valoch.

In 1895, a train arrived at a station; in 2001, planes flew into buildings. While it is most likely a popular myth, the audience reacted with awe and terror when they watched the iconic 50-second film by the Lumière brothers. In 2001, a global audience watched a live stream of buildings collapsing under the sheer force of melting steel. In-between lies the 20th century. Appearing as an accumulation of objects in flux, Versatzstücke criss-crosses some of the past century’s trajectories that continue to define or haunt today’s societies. The works in the exhibition, ranging from 1899 to 2002, are assembled fragments in response to artistic and political events of the 20th century and often relate to issues of violence, terror or collective as well as individual trauma. At the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, these objects, in their physical presence, refer to the seemingly unstoppable excessive acceleration of the current digital and immaterial age, itself defined by power-consuming data centres that manage our digital identities and are in the hands of a few privately owned companies that have unparalleled financial and political power.

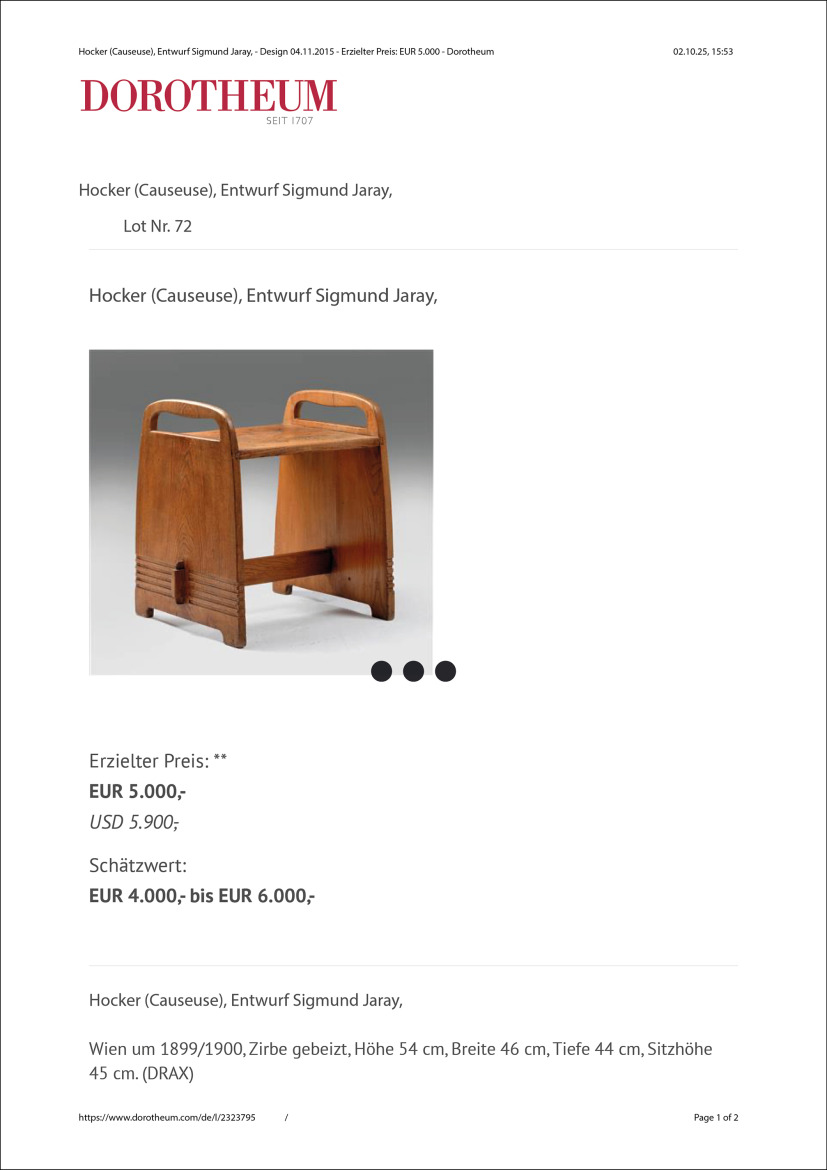

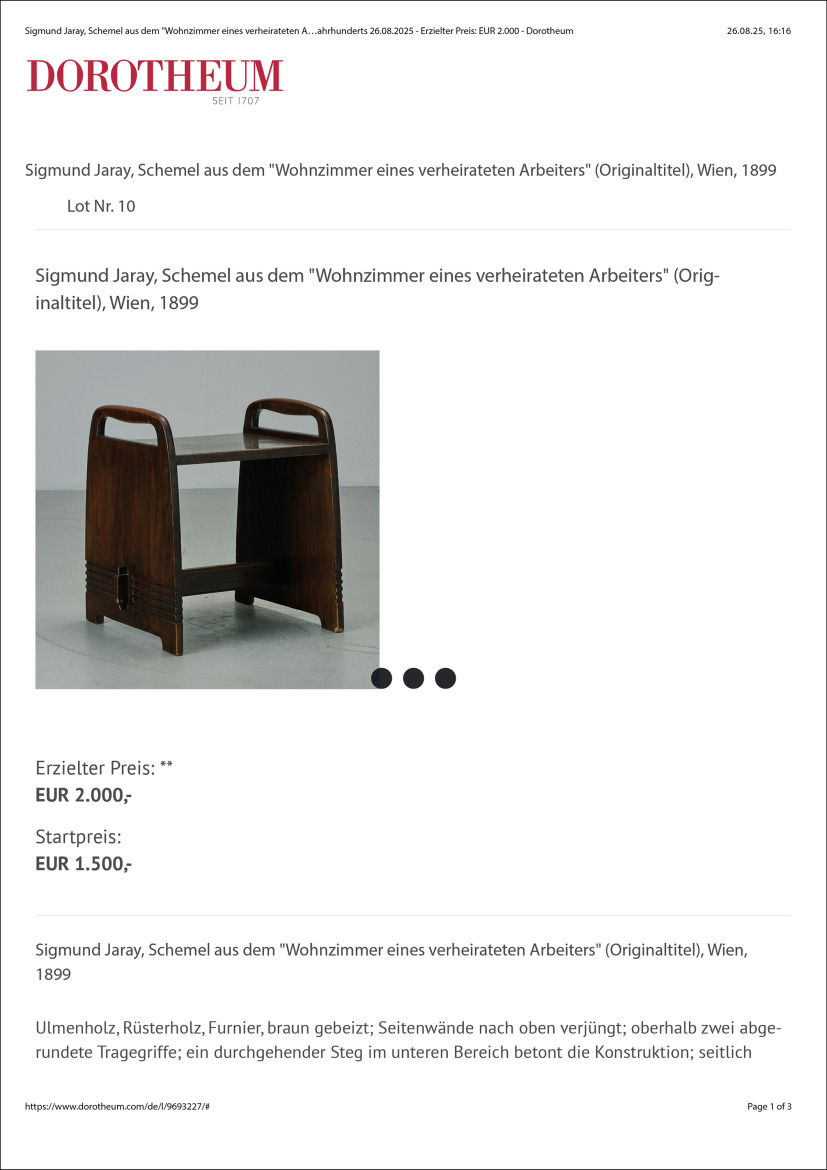

In 1899, Sigmund Jaray, an ancestor of Tess Jaray, who was born in Vienna in 1937, won second prize for Wohnzimmer eines verheirateten Arbeiters, which is now in the MAK Museum’s collection. The Jaray family moved to Vienna to work on the construction of the Ringstrasse, as well as the 1873 Weltausstellung held in the Prater. Jaray’s award-winning room is an exception to the familiy company’s more conservative approach, with its subtle Art Nouveau lines and sense of lightness, yet it is based on the idea of improving the living conditions of the working class. Fast forward to 2015 and 2025: a stool from the aforementioned room was auctioned at the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna. A transitionary venue for a diverse range of goods, Dorotheum played a major role in the resale of looted Jewish goods under the Nazi regime; however, all relevant documents proving these allegations were lost at the end of the Second World War. The stool’s physical absence from the exhibition, and it’s representation through a simple PDF printout, highlights the transient nature of commodified goods and is a metaphor for the absence of the Jaray family from contemporary Austrian society.

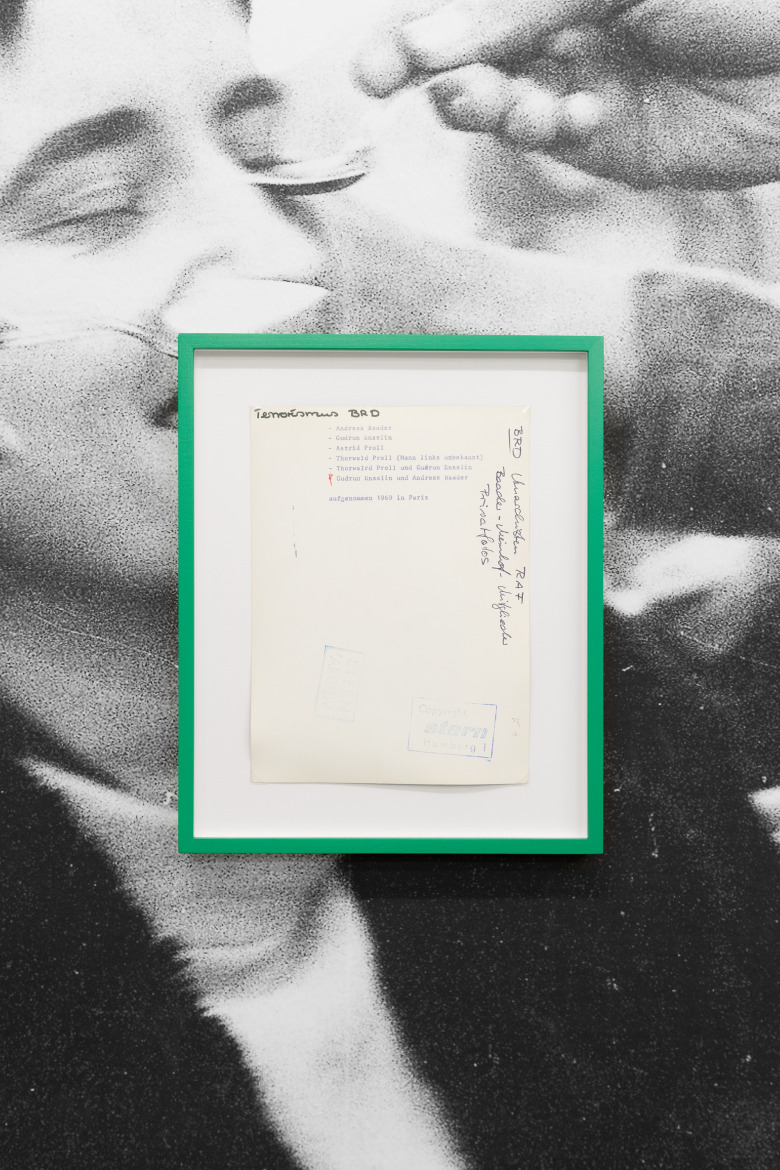

In 1967, Benno Ohnesorg was killed by German police during a student protest in Berlin. Inspired by the student movement of the time, Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader concluded that more radical forms of protest were needed against the perceived post-fascist German state. Consequently, in 1968, they set fire to a shopping centre in Frankfurt, were caught by German police shortly thereafter, put on trial, and sentenced to three years in jail. During the appeal, they escaped to Paris with a group of supporters. Astrid Proll, a 22-year-old photography student at the time, joined the group on their escape to Paris, taking her Minox half-frame camera with her. Once in Paris, the group went to the famous Café de Flore, a popular hangout for intellectuals and artists, where Proll put the camera on the table. In an act of collective ownership, the camera was passed around and the group took the now famous photographs of each other. While the photos initially appear reminiscent of youth culture or fashion snaps, they would become the last private, pre-institutionalised images of the group members who, at this time, were forming the RAF (Red Army Faction), which created political upheaval in Germany in the 1970s and 1980s. Eventually the roll of film was sold off to Der Stern magazine that licensed these photographs, disregarding the photographers’ copyright. The exhibition shows an enlarged segment of a photo of Astrid Proll with the back side of a framed original photo from Der Stern magazine archive on top. The photograph itself is hidden, yet the labels and text on verso classify the depicted as ‘terrorists’ and ‘anarchists’.

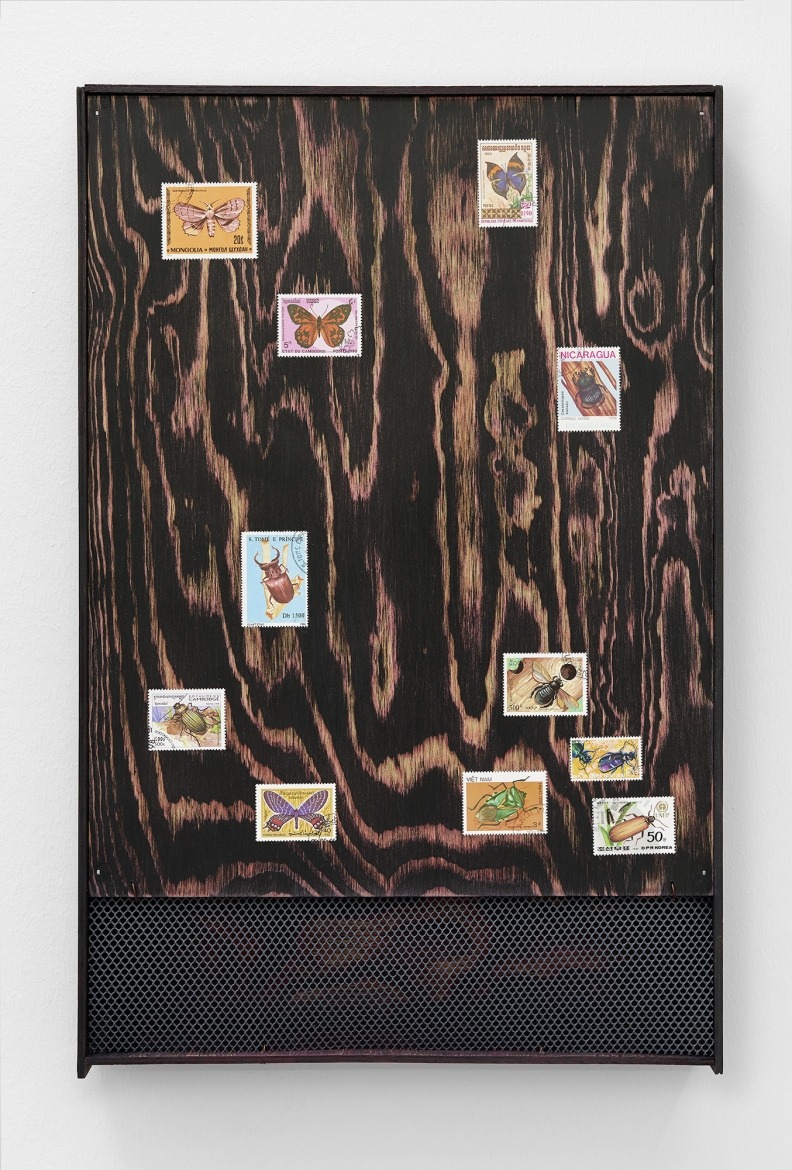

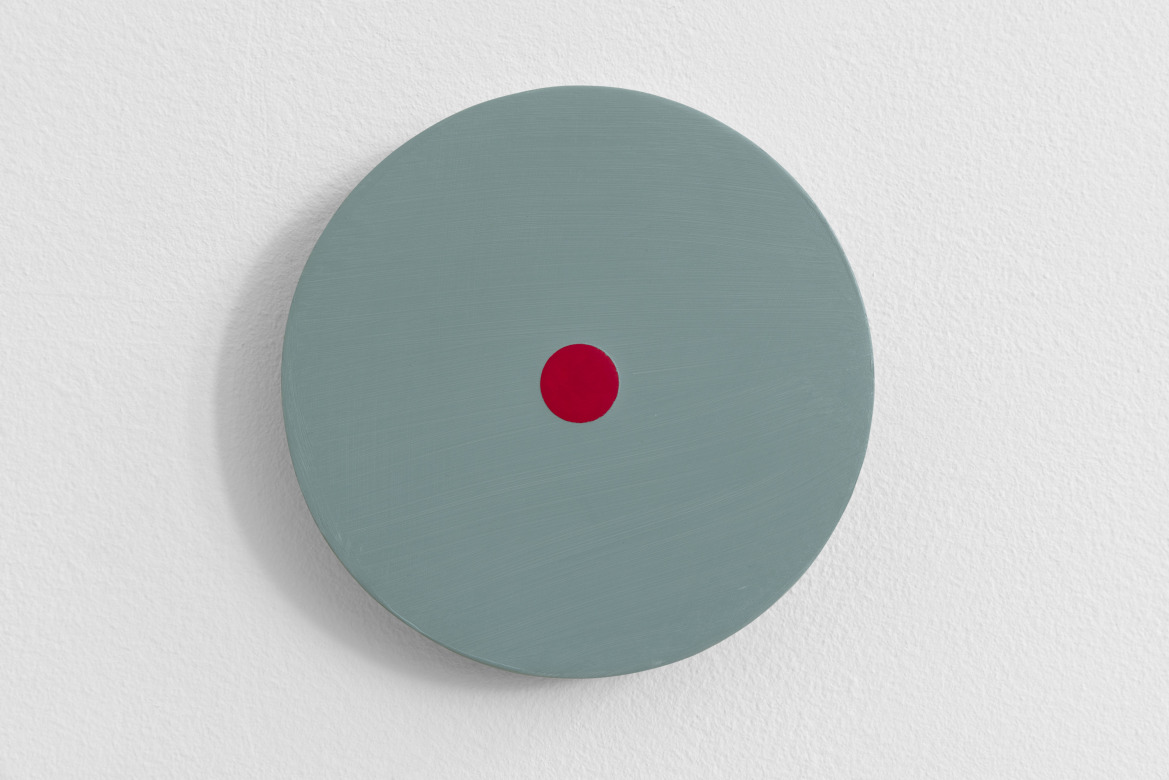

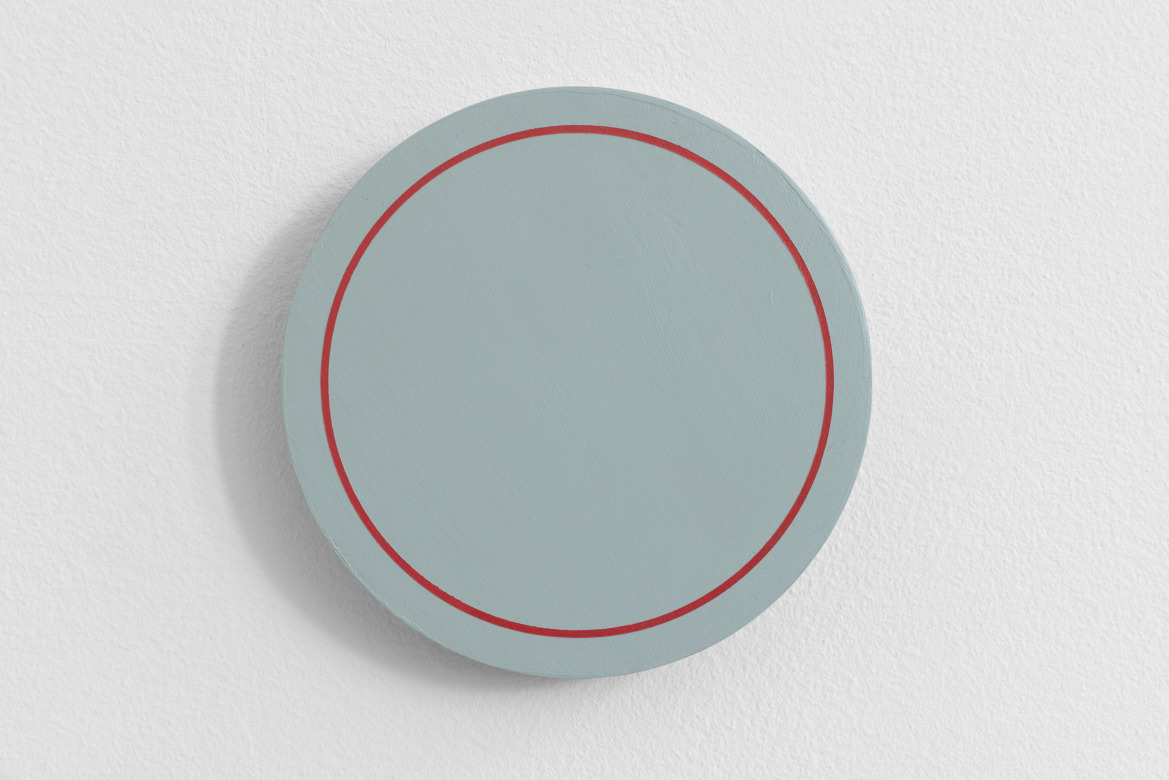

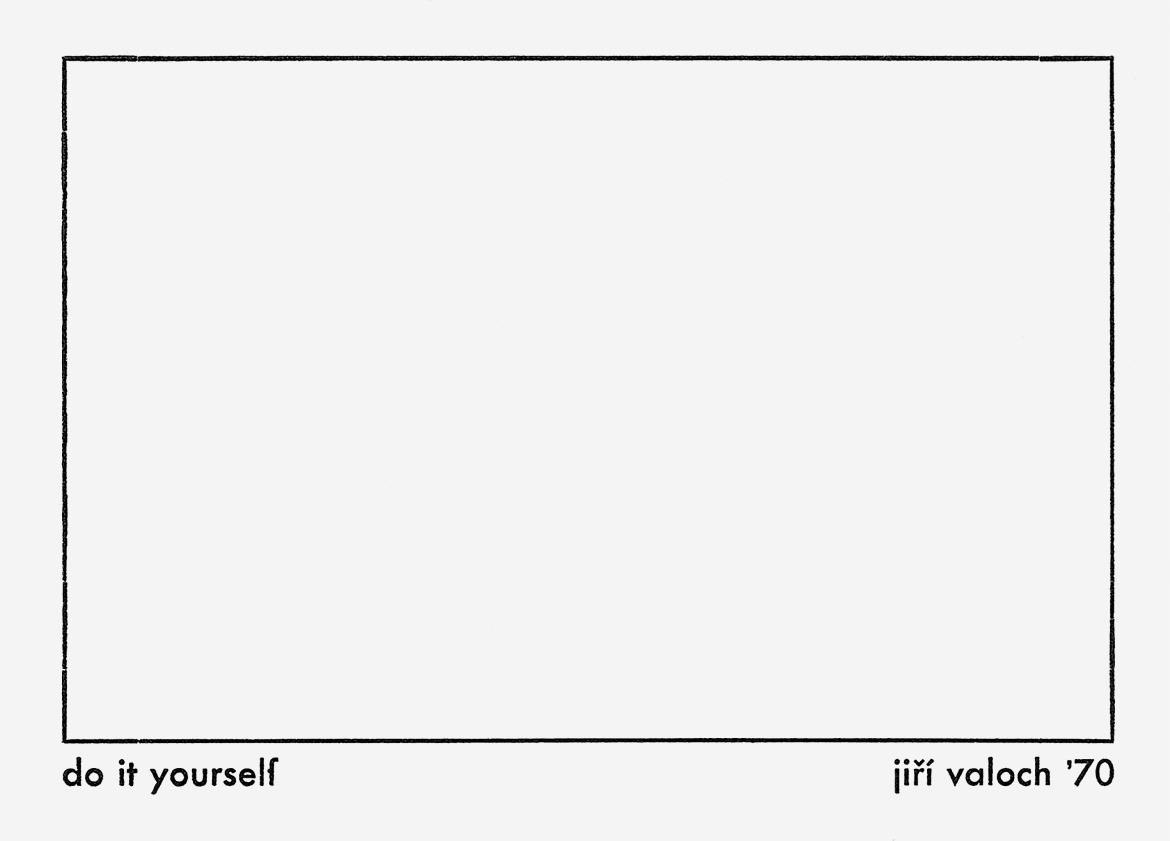

In 1970, the Czech conceptual artist Jiří Valoch sent a postcard entitled Do it yourself by mail across borders and countries. This simple gesture undermined existing censorship in Czechoslovakia and encouraged recipients to create their own artwork. On one hand political protest, the postcard enabled it’s recipient to develop their own creative ideas while Valoch himself was already barred from exhibiting in his home country. Do It Yourself is a frame within a frame, a blind mirror of personal self-reflection in the face of systemic silencing.

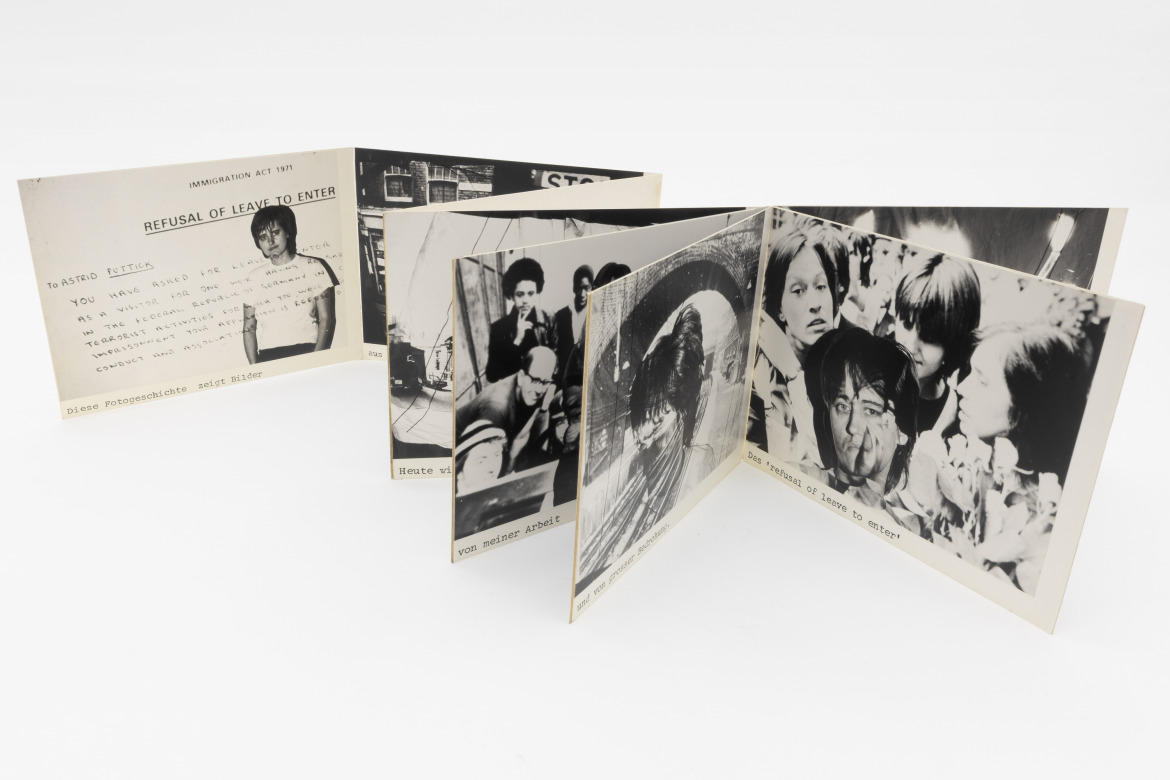

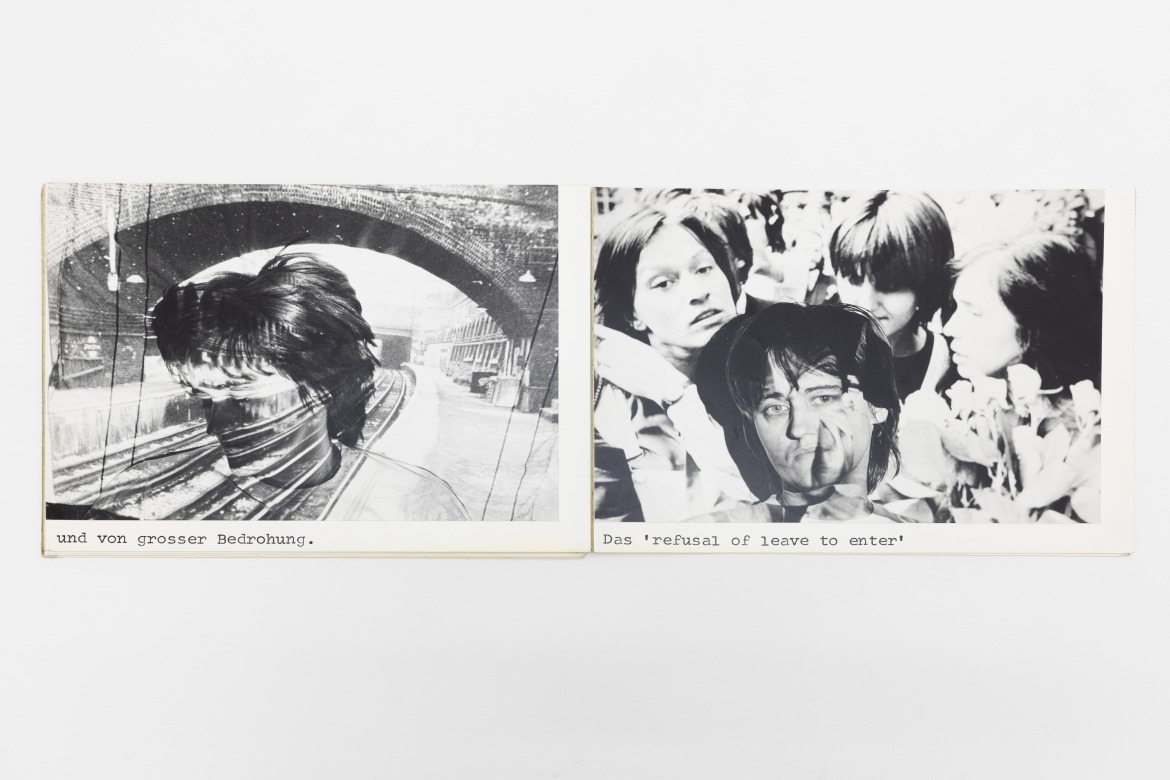

In 1981, Proll was extradited to Germany after previously being imprisoned and held in solitary confinement in Germany, escaping to London and living illegally under the alias Anna Puttick. Following her extradition, Proll did not need to finish her jail sentence for her participation in the RAF due to the severity of the previous solitary confinement. She returned to work with photography and submitted the exhibited leporello entitled Refusal of Leave to Enter as part of her application to film school. This never before shown work reads like a photo story, consisting of 11 self-portraits with images relating to her time in London, projected onto her body.

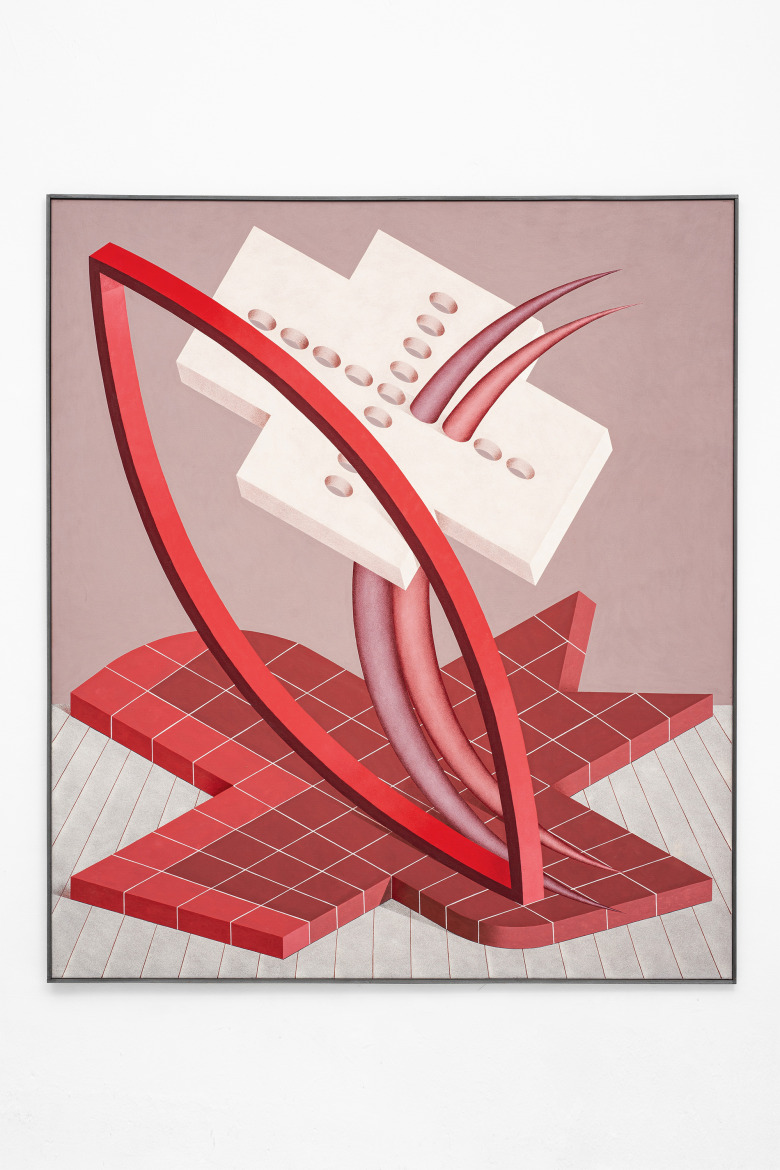

In 1982, Elke Denda created Flugzeugtisch, which she produced during her studies at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. This table-like yet dysfunctional movable object with a Formica top and a downward-sliding aeroplane breaks the boundaries between artwork and design object, and appears to be deeply influenced by Postmodernism. Denda started to develop a successful career in the arts but later withdrew from the art world to open a catering service and restaurant.

In 1983, Kazuko Miyamoto, since 1974 a member of the women’s art collective A.I.R., walked around Lower Manhattan from A.I.R. gallery to the alternative performance art space Franklin Furnace, dressed in a blue blanket. Her head was covered with what appeared to be a white plastic bag. Entitled Waiting for the Carnival, the fragmented remaining set of photocopies documenting this performative walk is on display. Although Miyamoto’s walk had a clear beginning and end, it also represents the many marginalised individuals walking seemingly lost through the streets of Manhattan. Miyamoto’s performance was in stark contrast to the glitzy, Wall Street-fuelled art world of 1980s New York. She pays tribute to an alternative vision of art that is less capital-driven, where collaboration, collectivity and community take precedence over hyper-individuality and capitalist obscenity. At the same time, she raises awareness of issues such as poverty, homelessness and displacement.

In 1988, Proll produced her graduation film, Der Zug aus Leipzig, in collaboration with Claudia Richards. In the film, the artists travel to the German-German border station at Büchen, where Proll interviewed East German pensioners who were allowed to cross the ideological divide from socialism to capitalism and back. As the train arrives at the station, the East-German travellers undergo border procedures, receive charitable food donations before continuing their journey to Hamburg. The film reflects on Proll’s own biography as an individual caught in-between political systems and nation states.

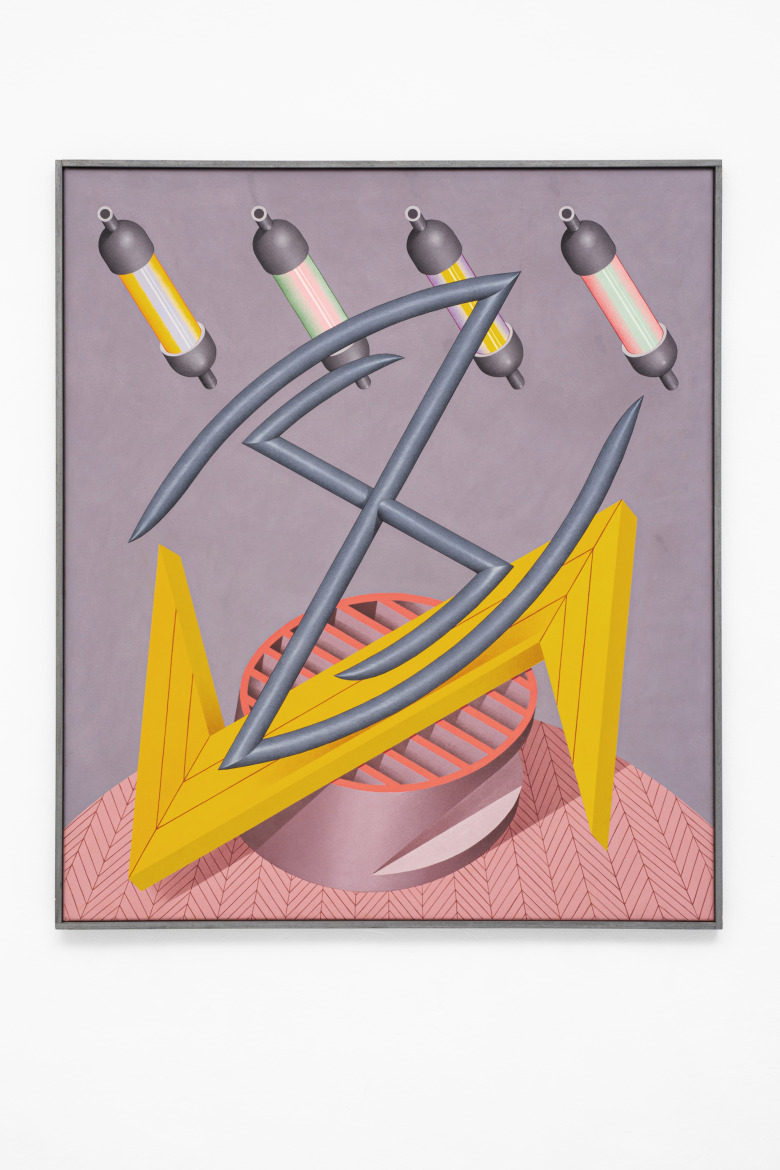

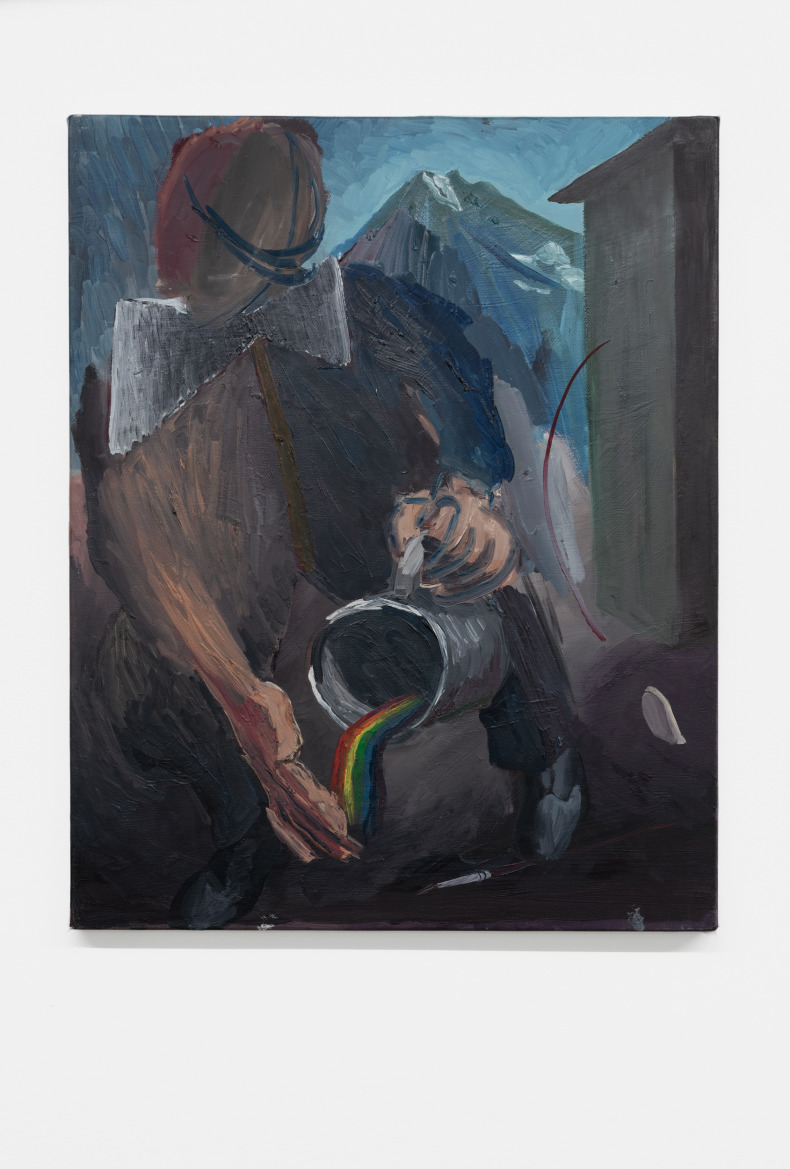

In 1989, the German painter Jobst Meyer created the exhibited work Konstruktion mit Kreuzscheibe und Haken. The date and arrangement of the objects make this work remarkable. A black, zigzag, cross-like shape, reminiscent of Rietveld’s 1932 chair, as well as Alchimia’s 1975 adaptation, sits atop a white-and-red, Superstudio-esque, checkered cross arranged with a pyramid-like form, a hook, and a circular saw blade. In the context of the year it was created, the painting could be interpreted as a visionary allegory of the looming consequences of the annexation of socialist East Germany by capitalist West Germany. The form, painted in a greyish black with the symbol of the cross, holds two identifiers of the ruling CDU party under German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, hooking the East with its commodified lure of freedom while using a saw blade to cut through the advances of West Germany’s socialist counterpart.

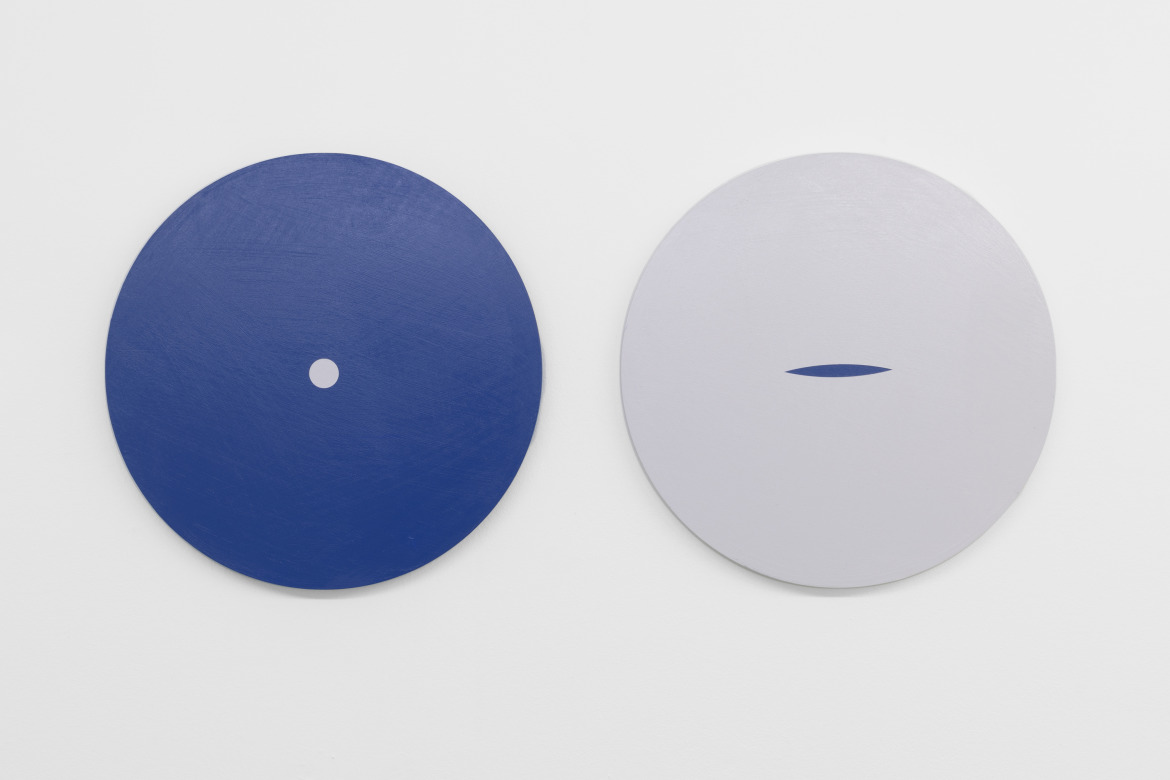

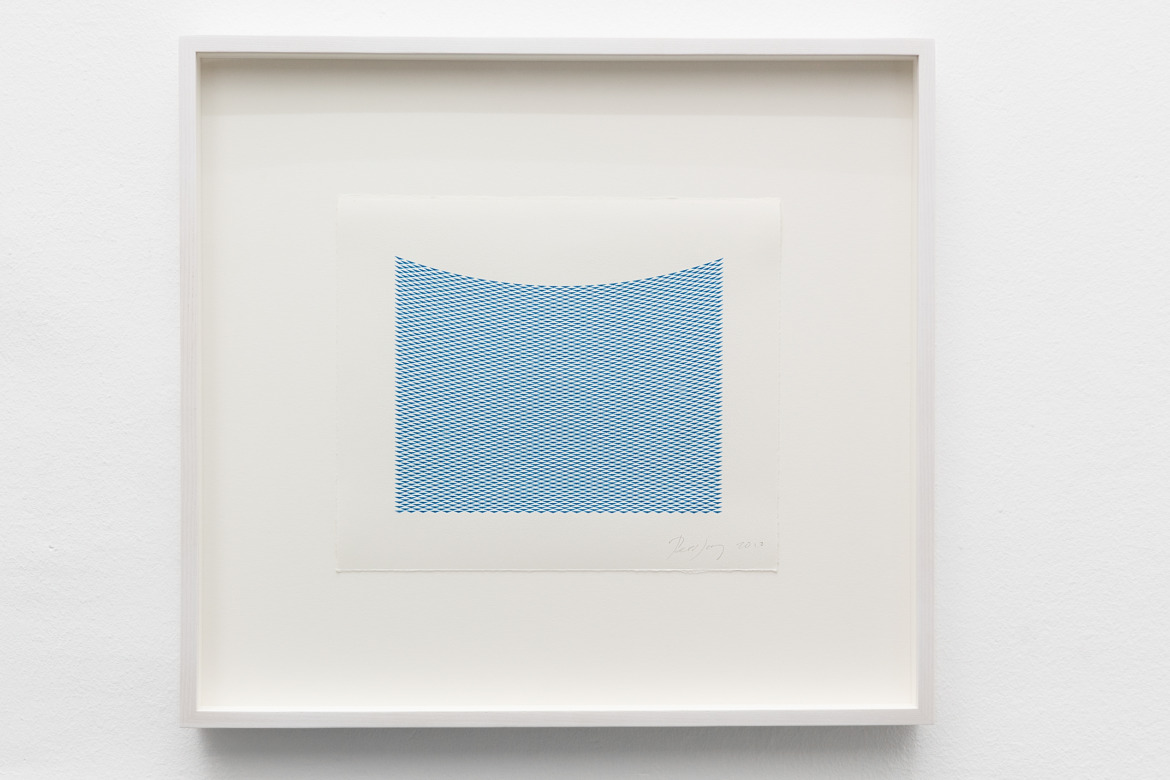

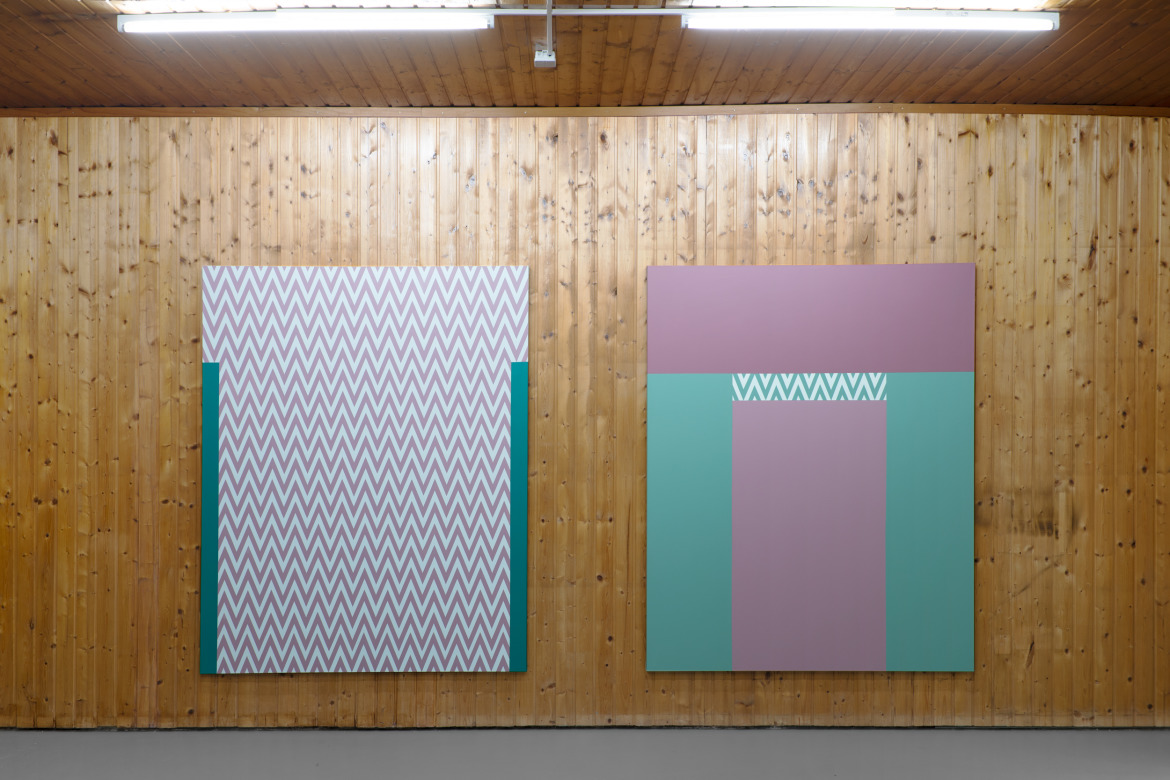

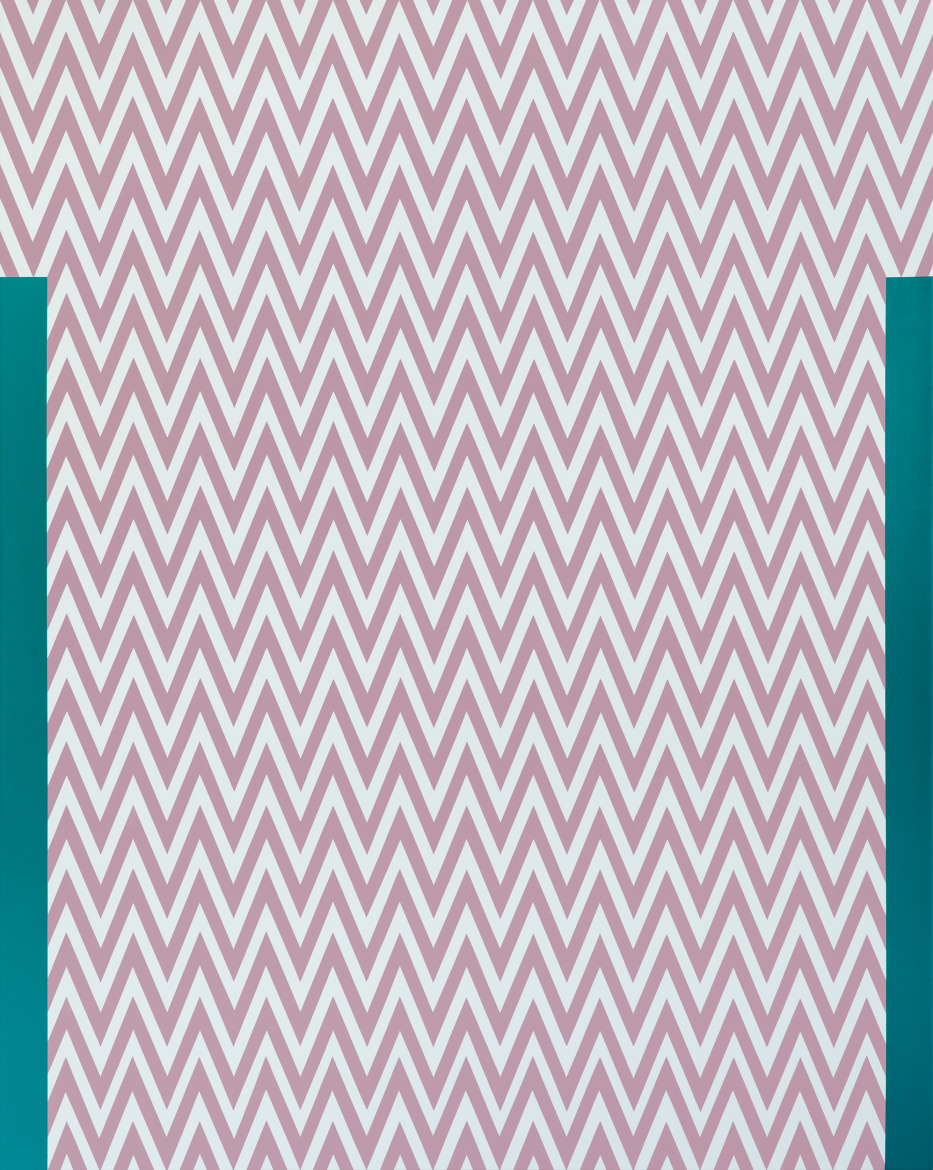

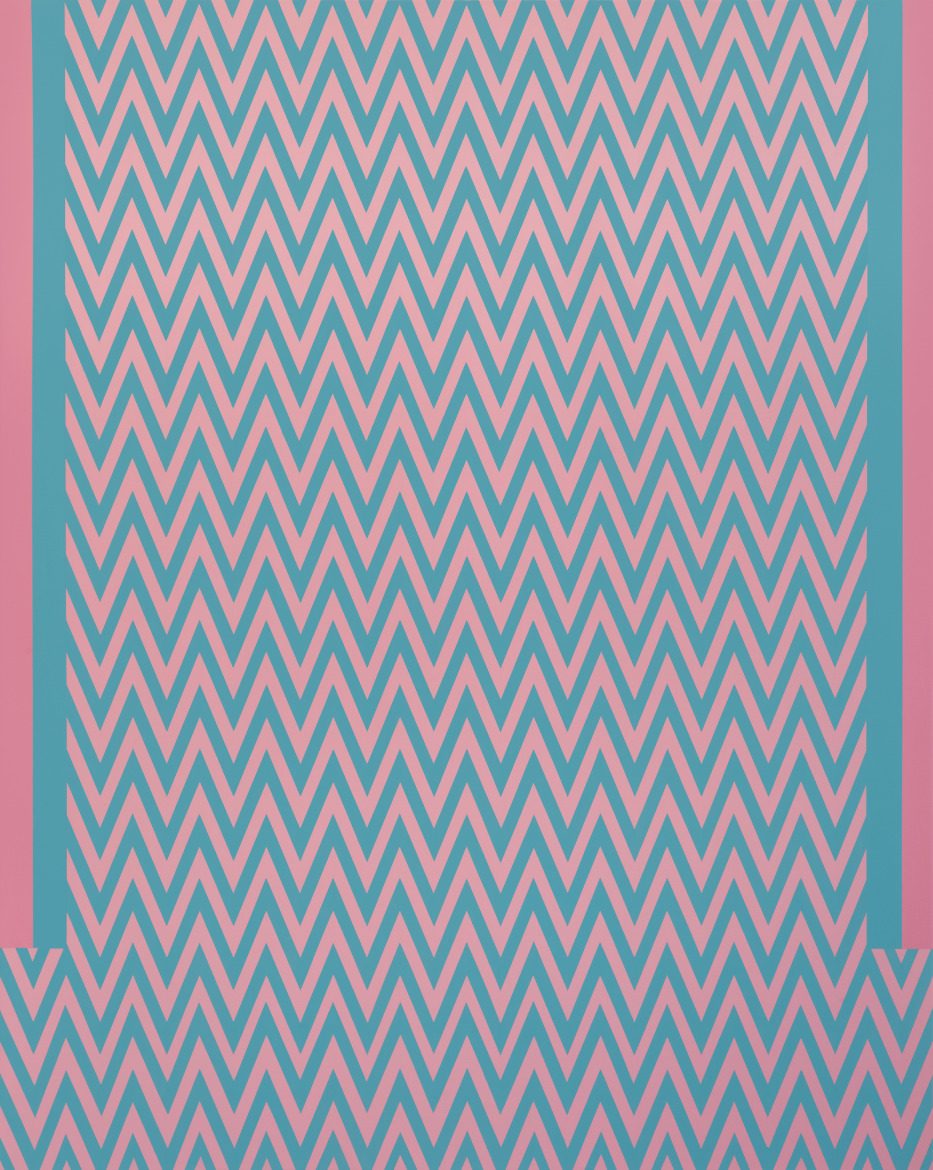

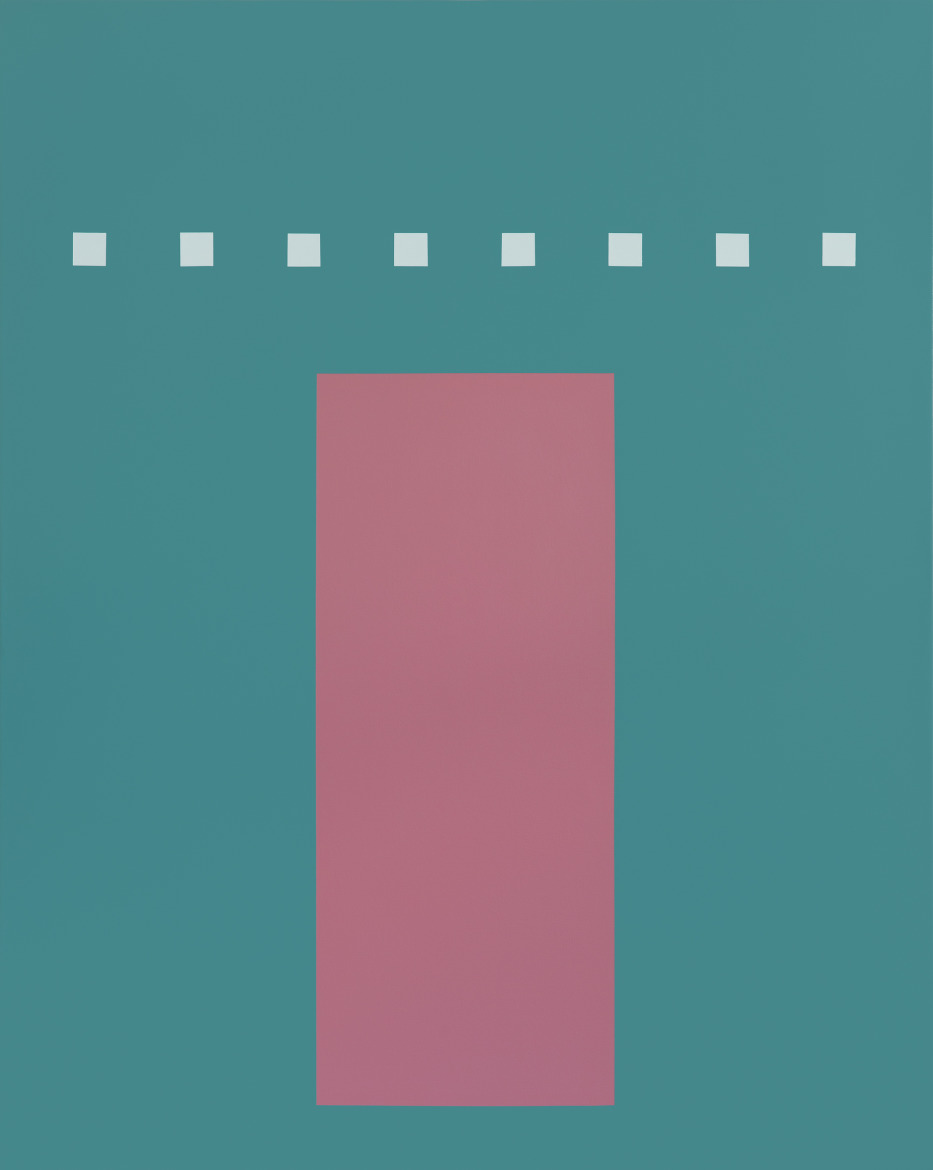

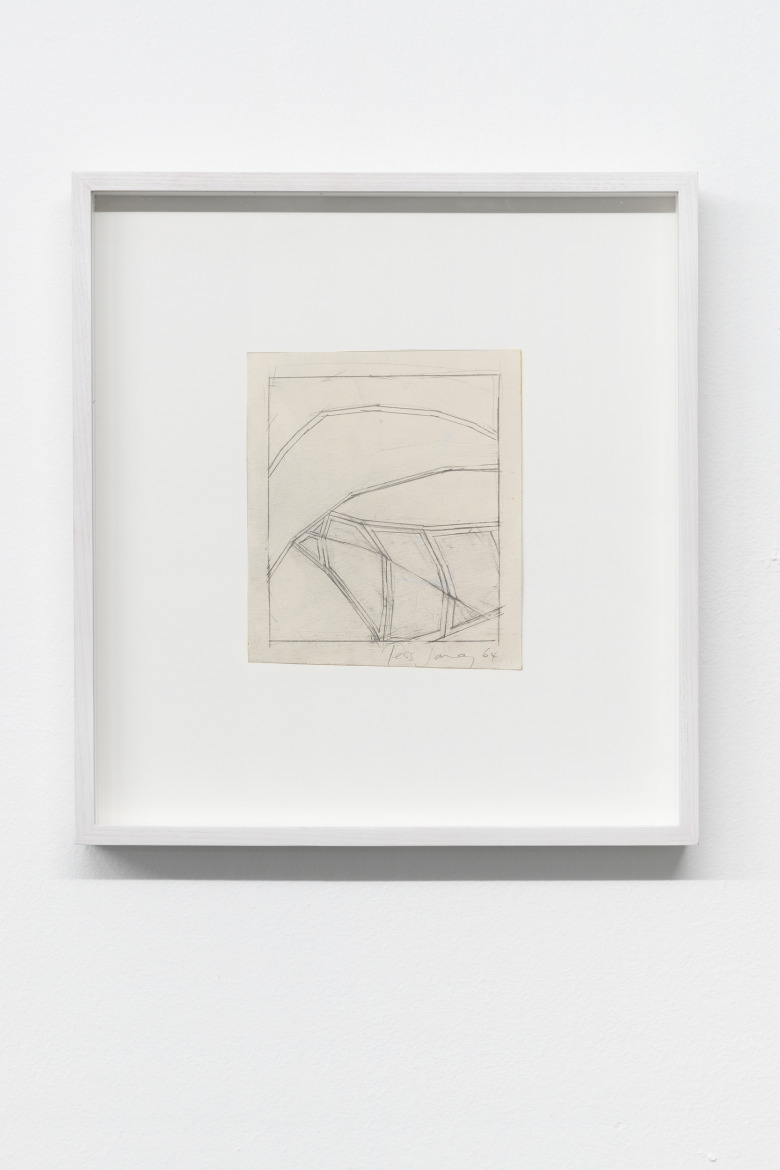

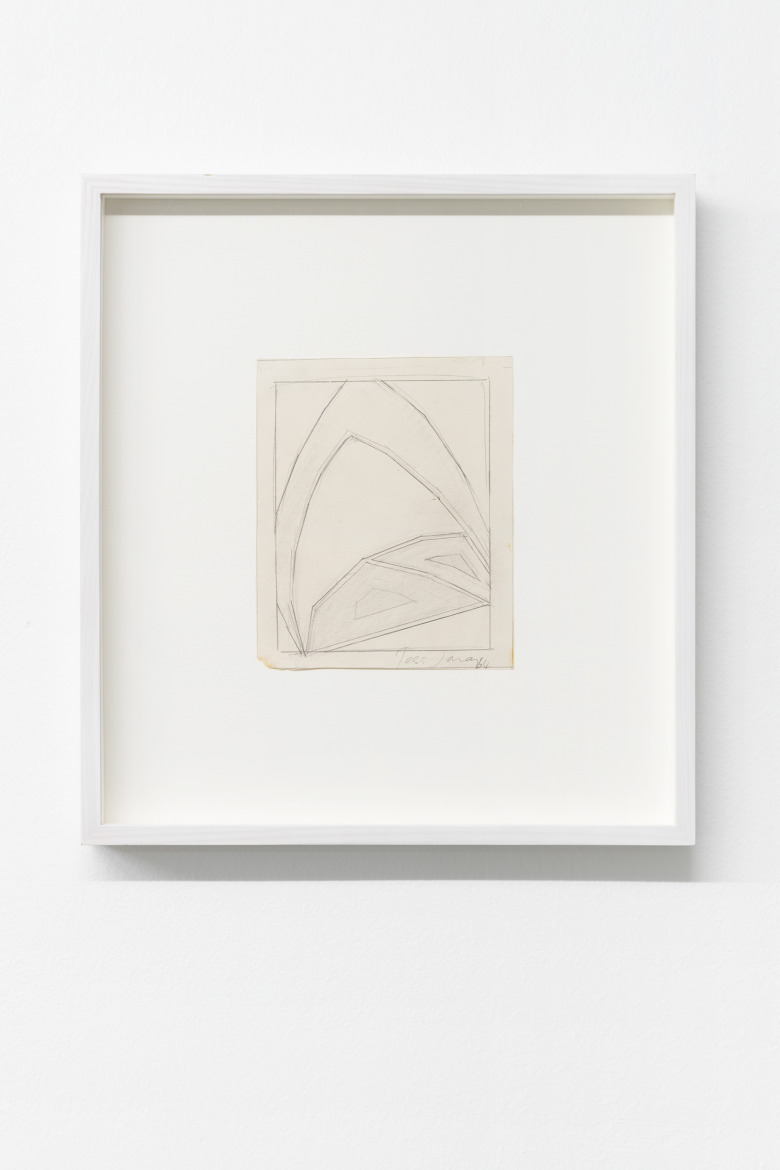

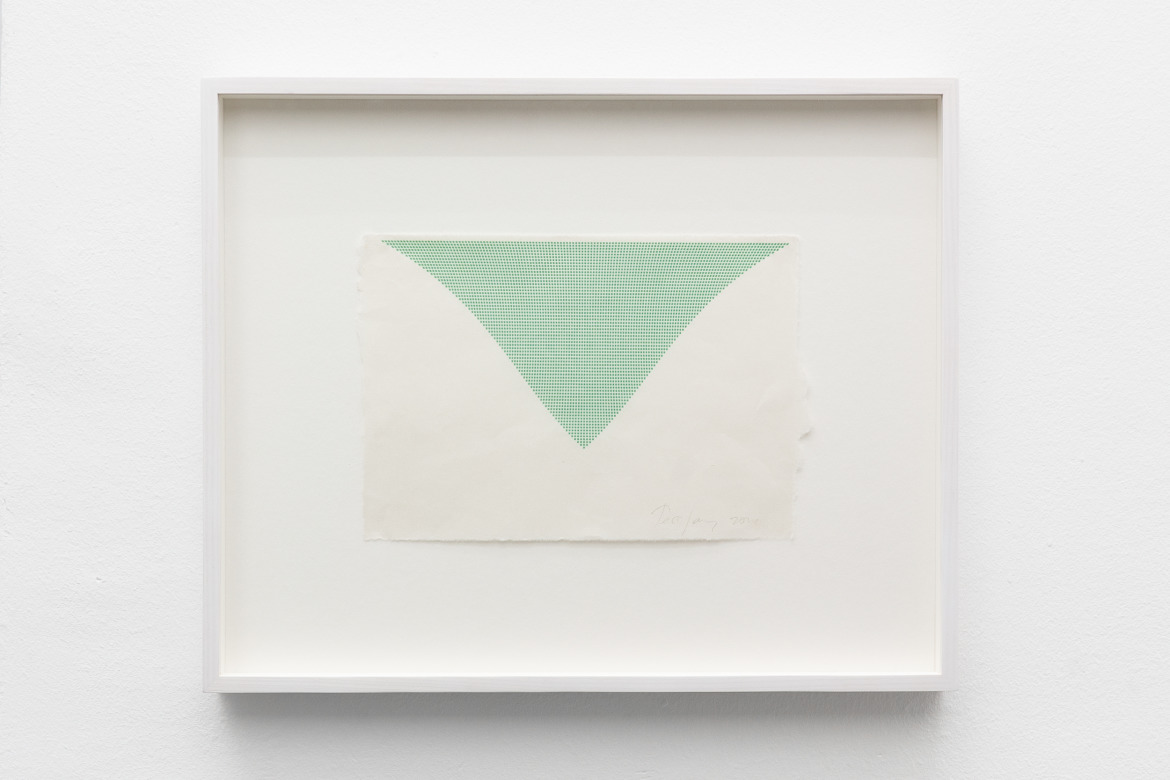

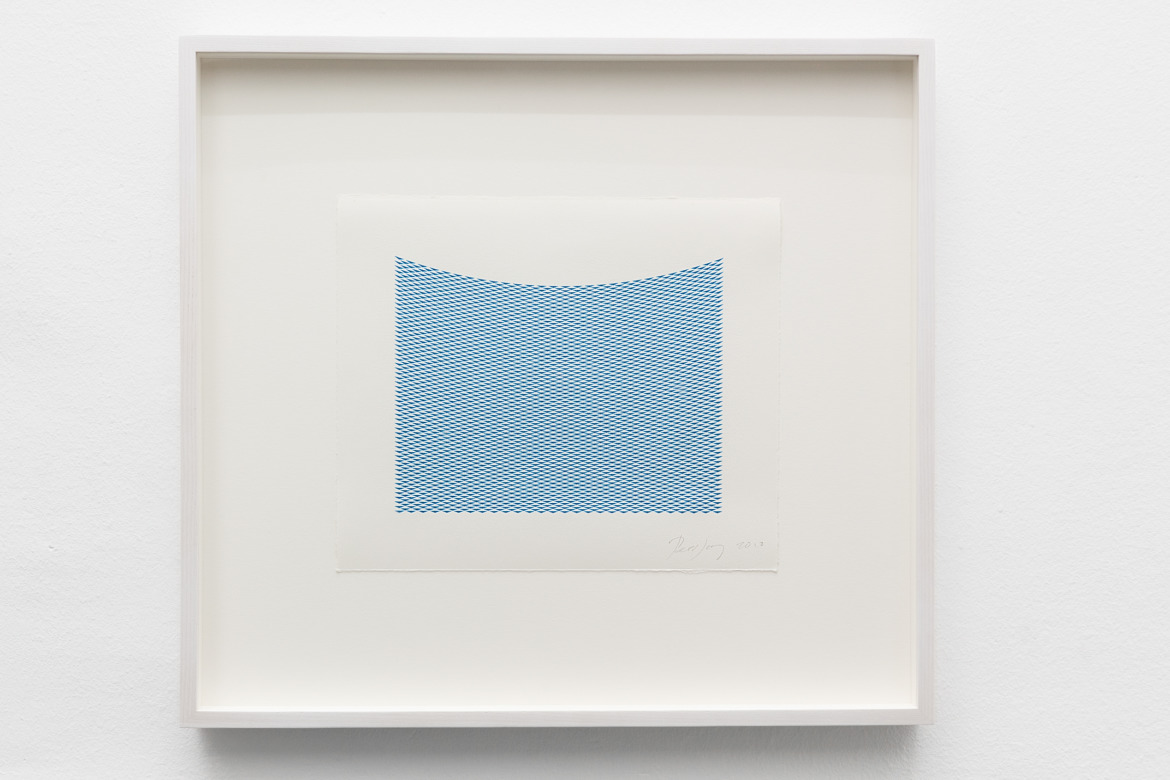

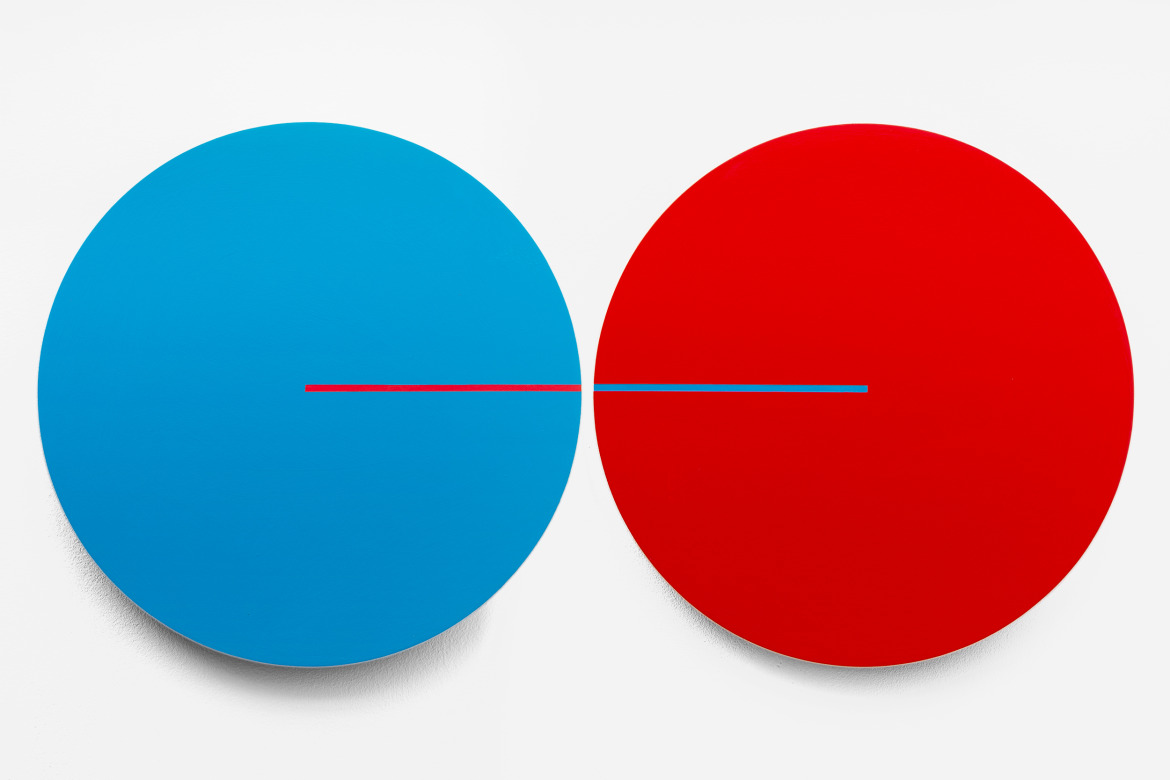

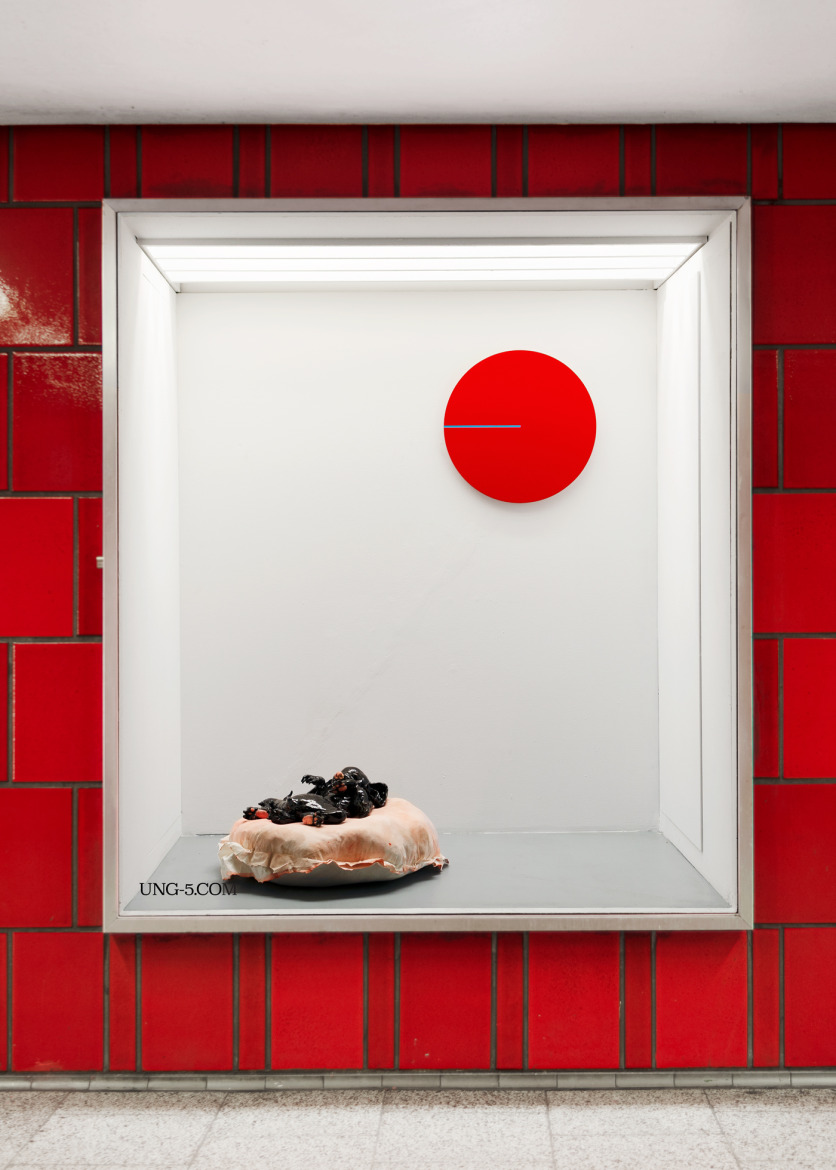

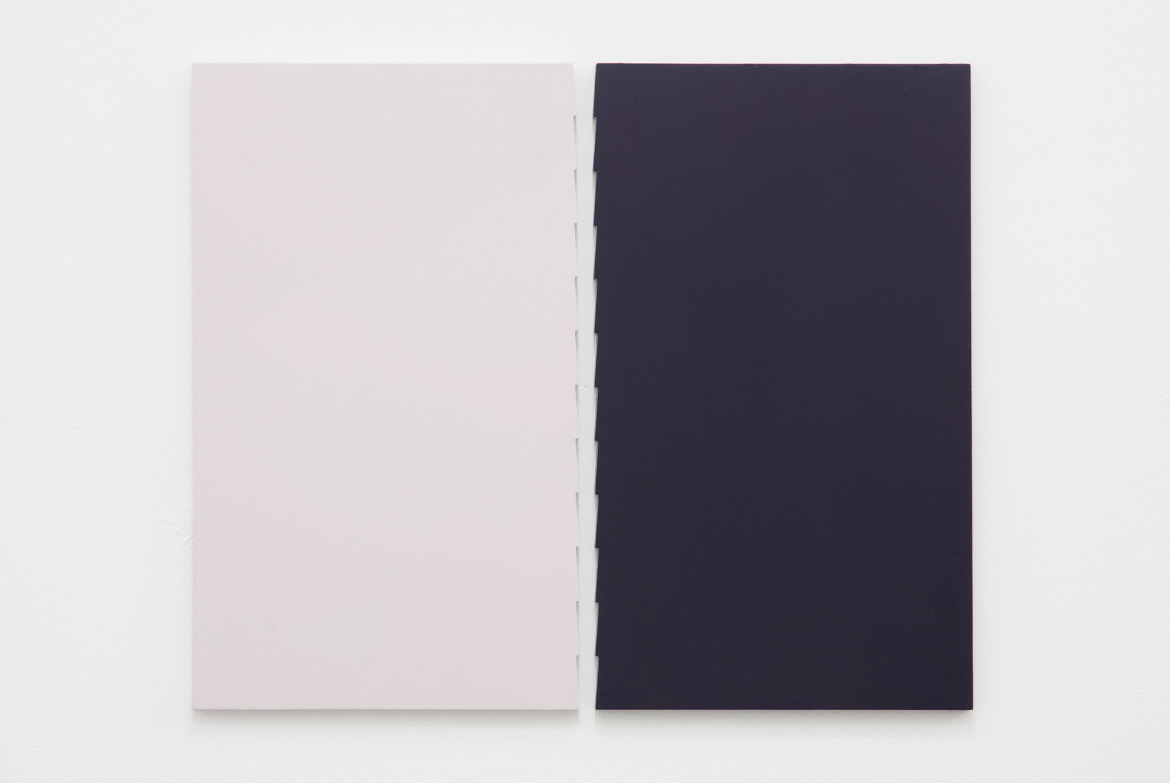

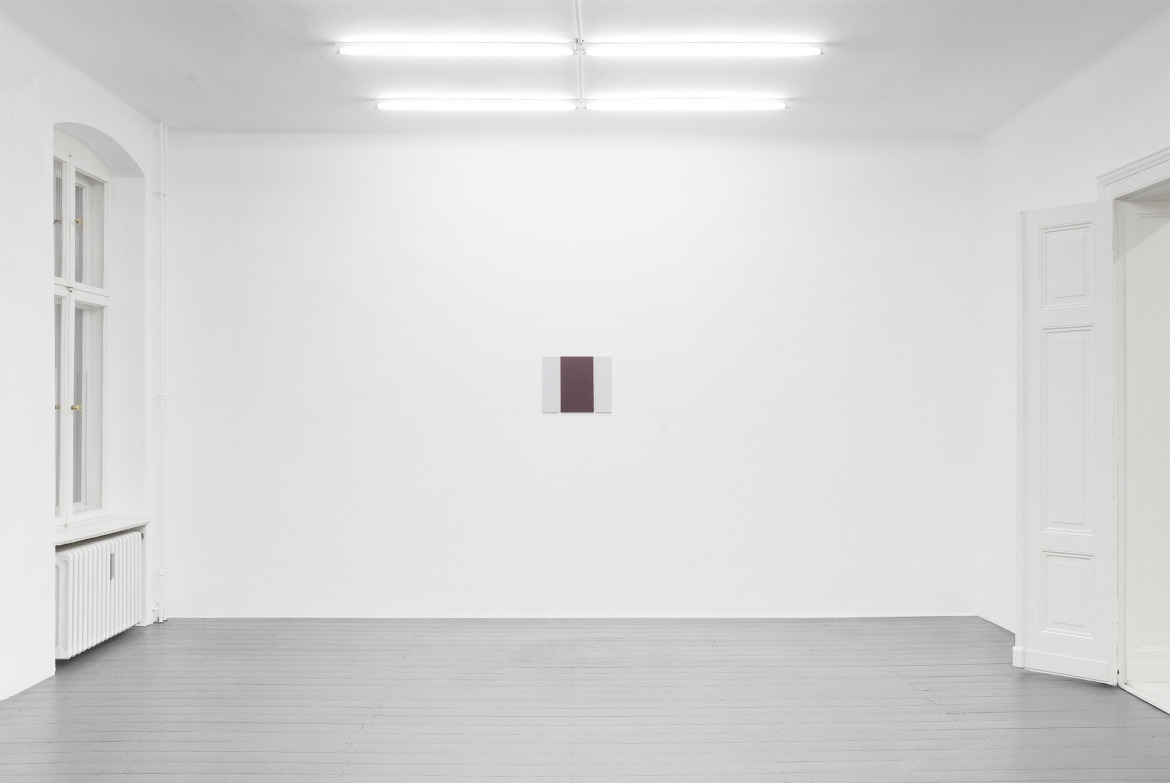

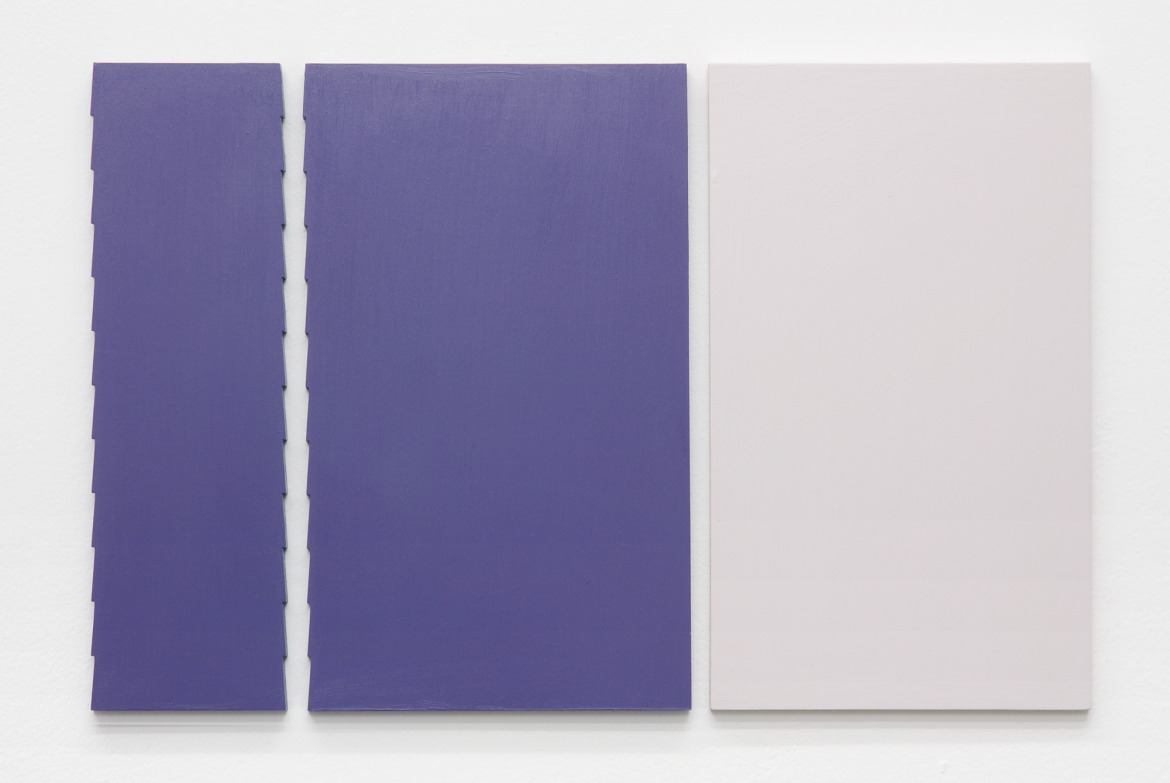

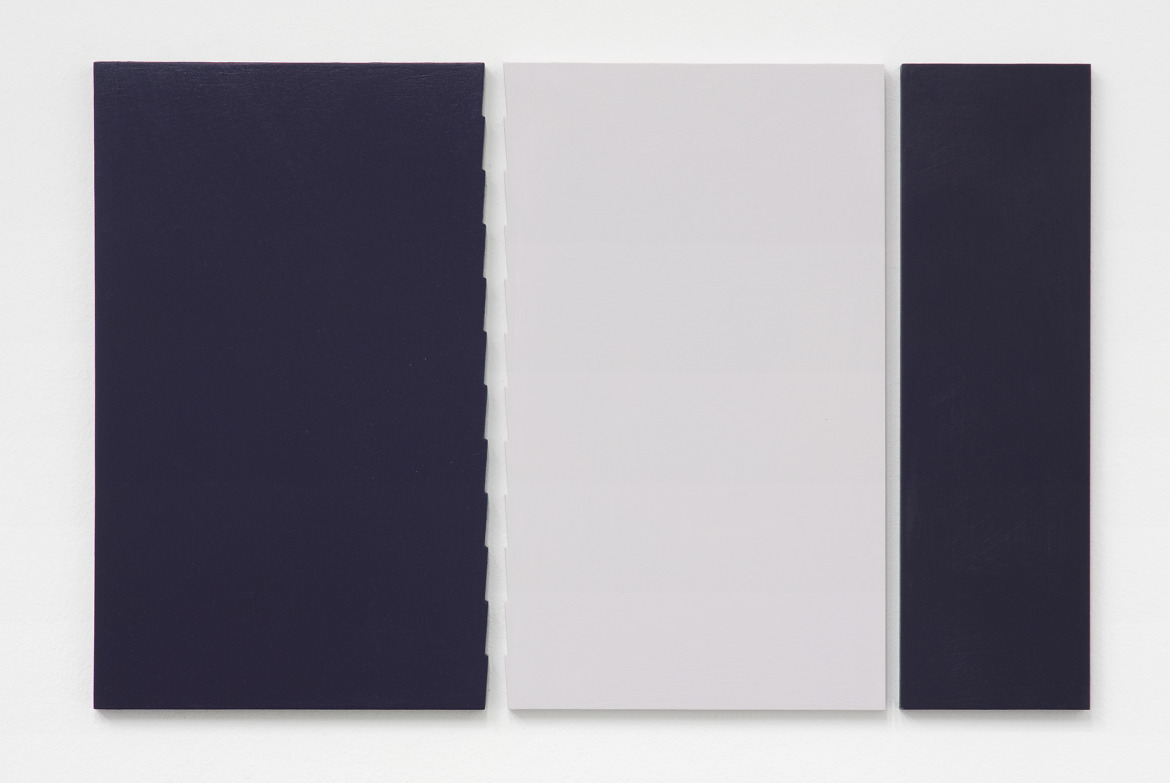

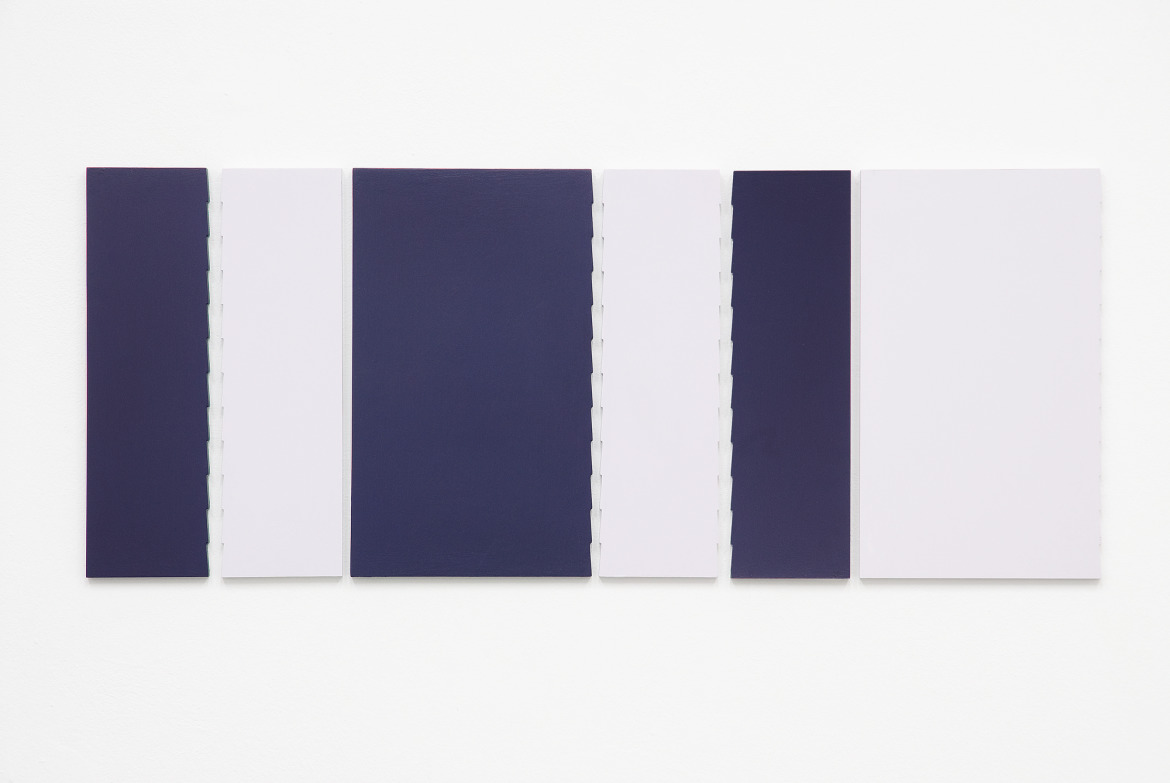

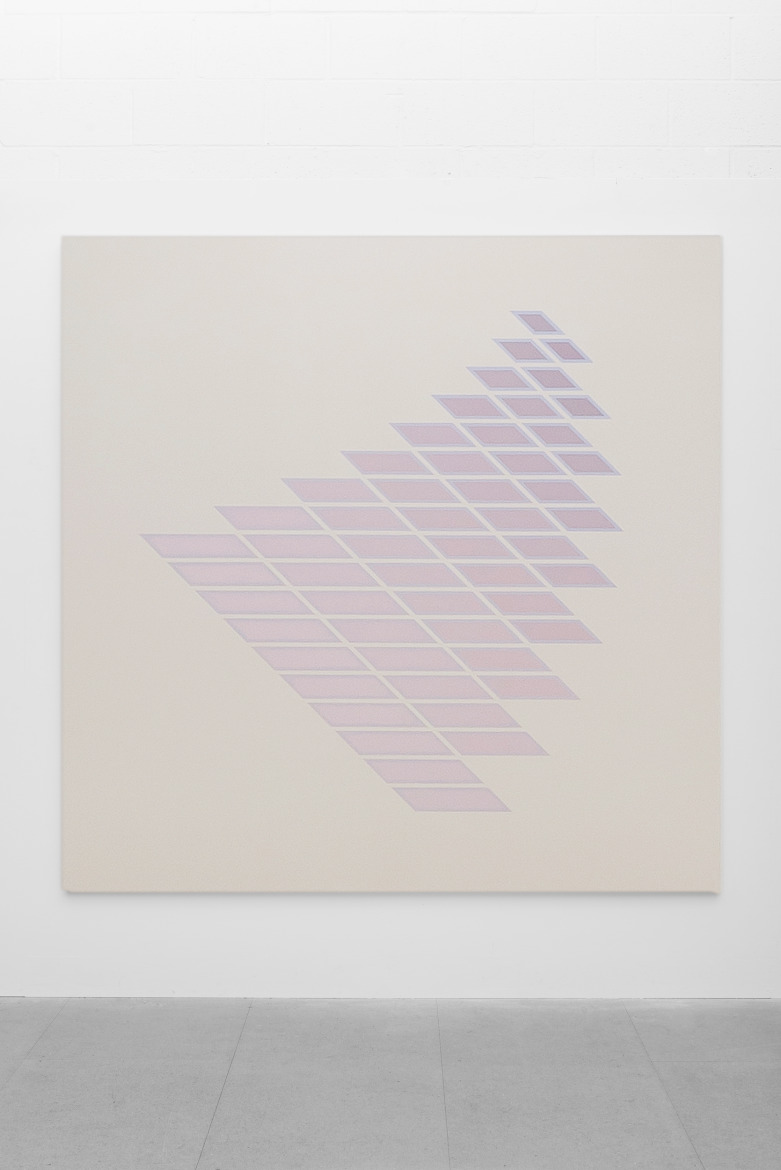

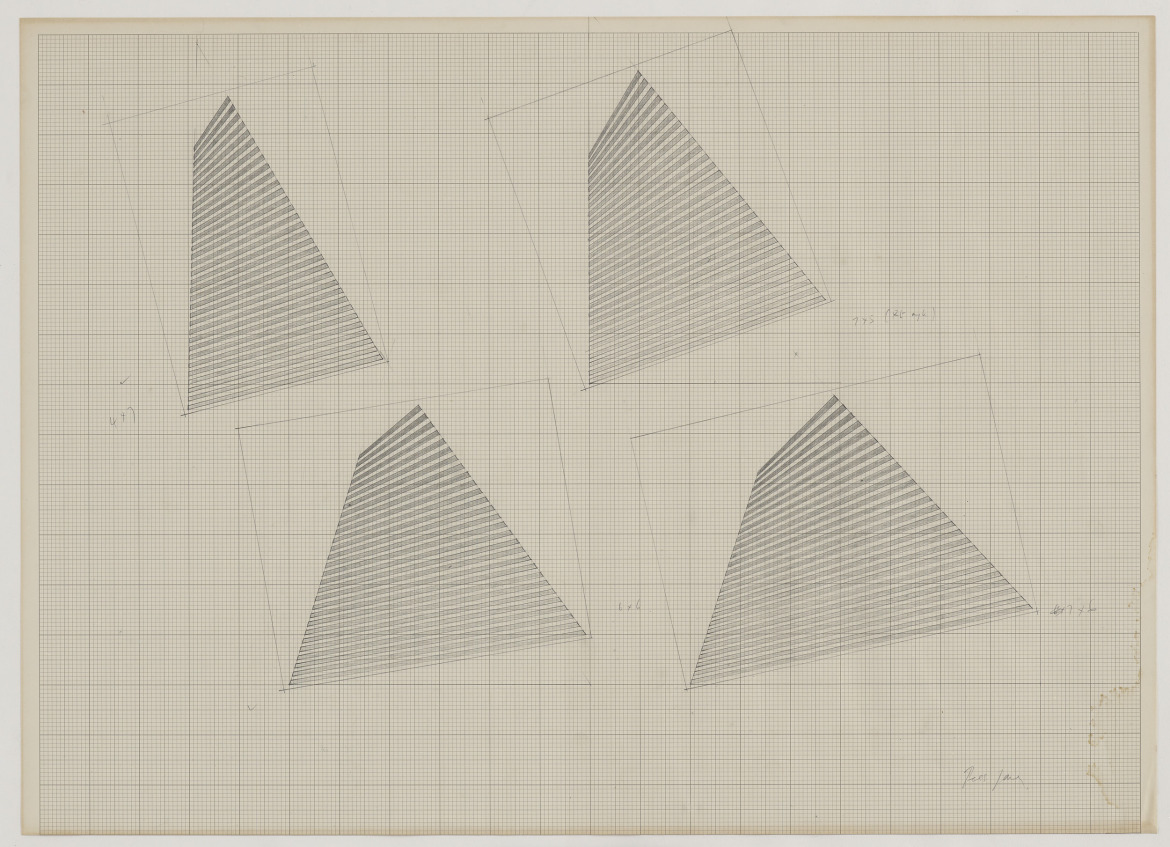

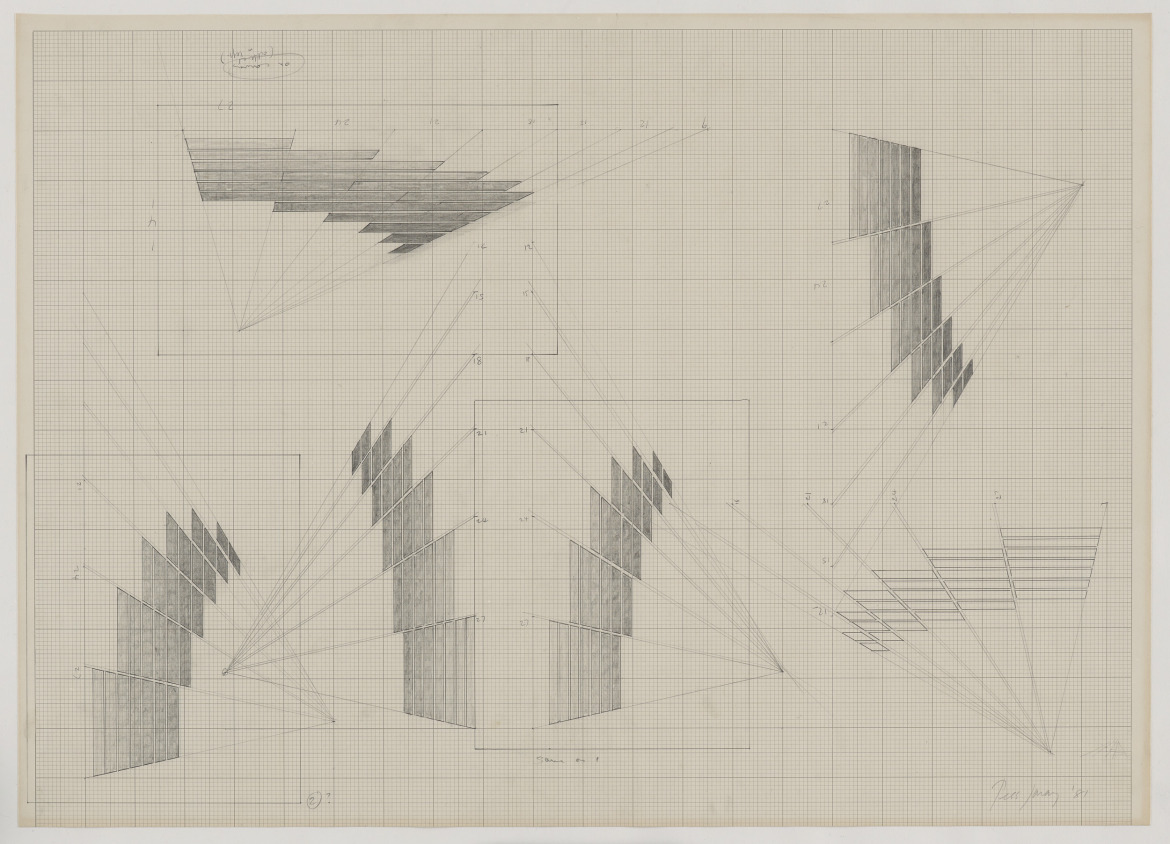

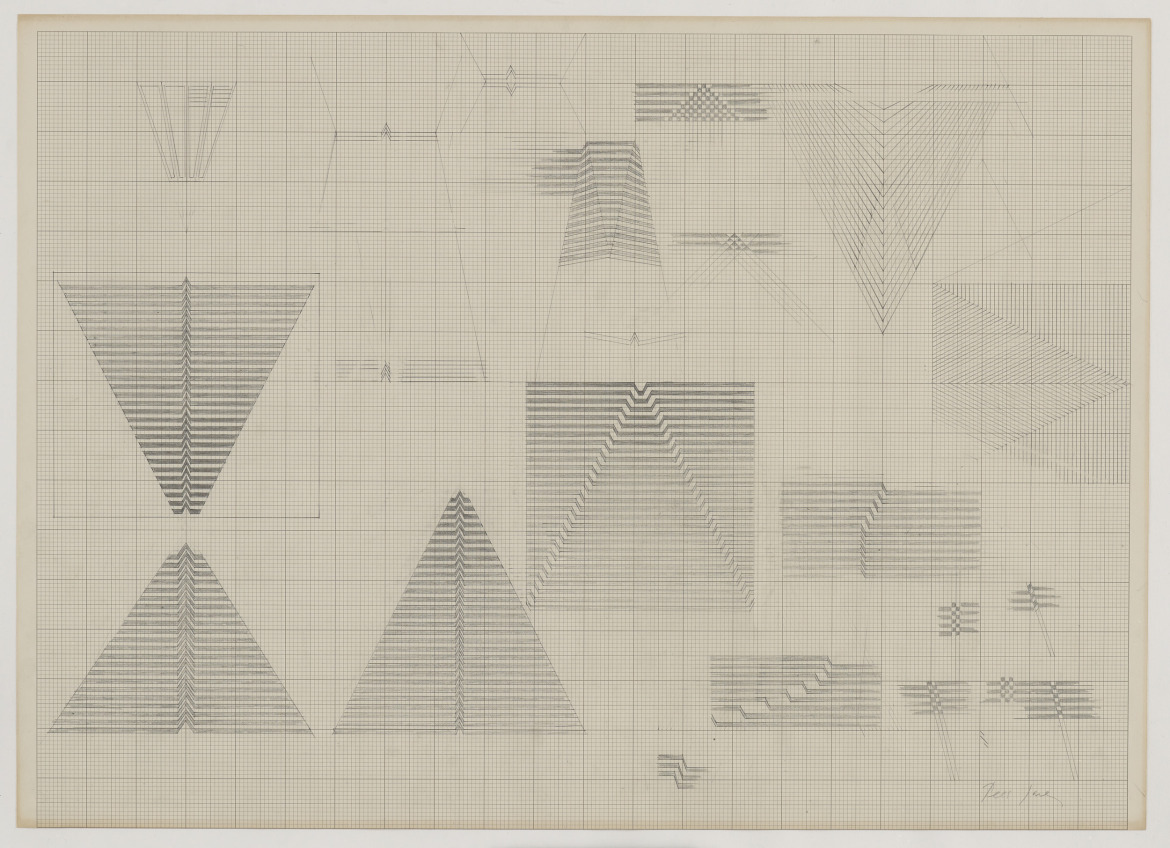

In 2001, Tess Jaray collaborated with German author W. G. Sebald on a series of silkscreen prints. The resulting book and set of prints were the first public exposure of Sebald’s poetry. Himself an emigrant from Germany to the UK, Sebald’s writings often refer to absence, alienation and exile, with the author frequently using trains and train stations as metaphors. Due to their close friendship, Sebald was very familiar with the Jaray family history, and the exhibited quote reads as a poetic yet precise reflection on contemporary society.

In 2002, Kathe Burkart performed American Woman in front of a small audience. Dressed in a burqa made from an American flag, the artist sat on a chair and gestured to music while video footage of and around 9/11 was projected onto her. This radical performance, at a time when the War on Terror had just begun, is likely one of the first critical responses to US politics in response to 9/11. Here, it also marks the end of the exhibition and symbolised the end of the 20th century.

Beginning with a train arriving at a station, we are now faced with airplanes bringing down seemingly invincible steel towers of Western dominance and capitalism. From here, the world is catapulted into a new dawn: a hyper-accelerated, multi-crisis era that leaves us all too often in states of disbelief, shock and awe. Yet the works on display also present forms of individual or collective response, of subversion to perceived norms, either within an artistic context or far beyond it.