EXILE is pleased to invite you to the opening of the solo exhibition Pictures on the Run at the gallery’s Erfurt location. The exhibition will present Astrid Proll’s widely-known photographs taken in November 1969 in Paris and is accompanied by a text from Alexandra Symons-Sutcliffe.

Autumn passed me by, and I did not notice

the entire season had passed. Our history passed me on the pavement…

and I did not notice.1

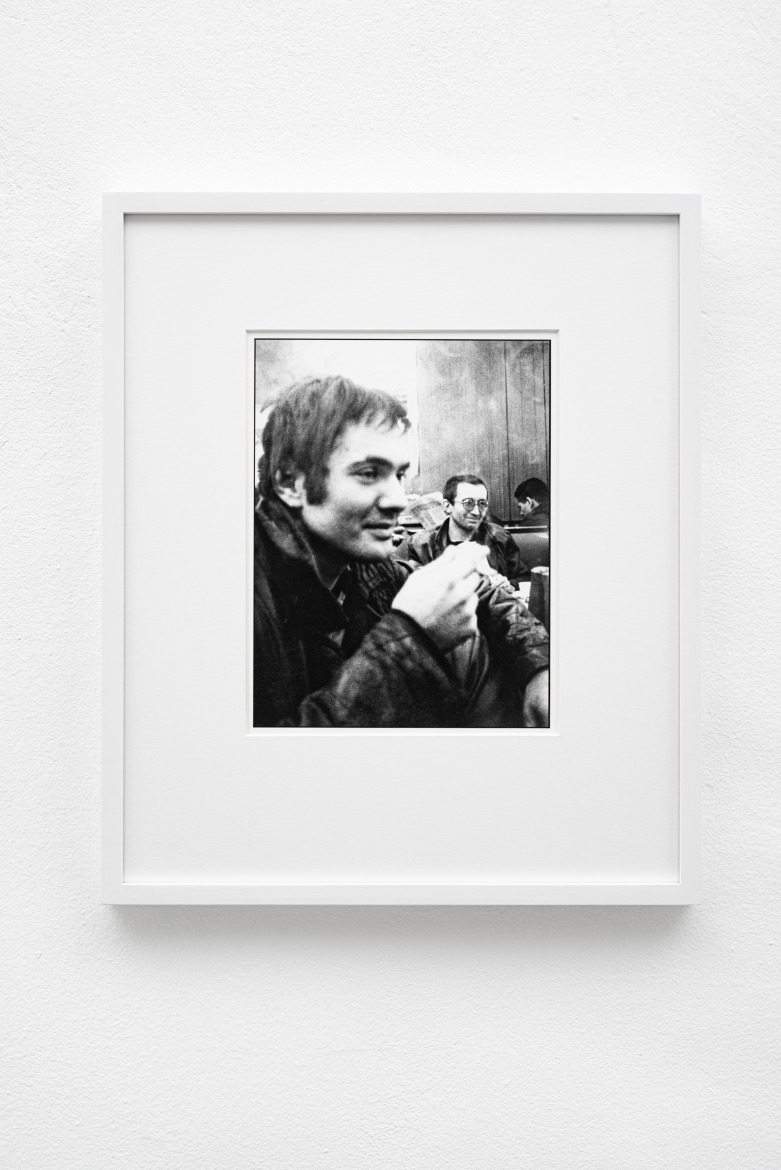

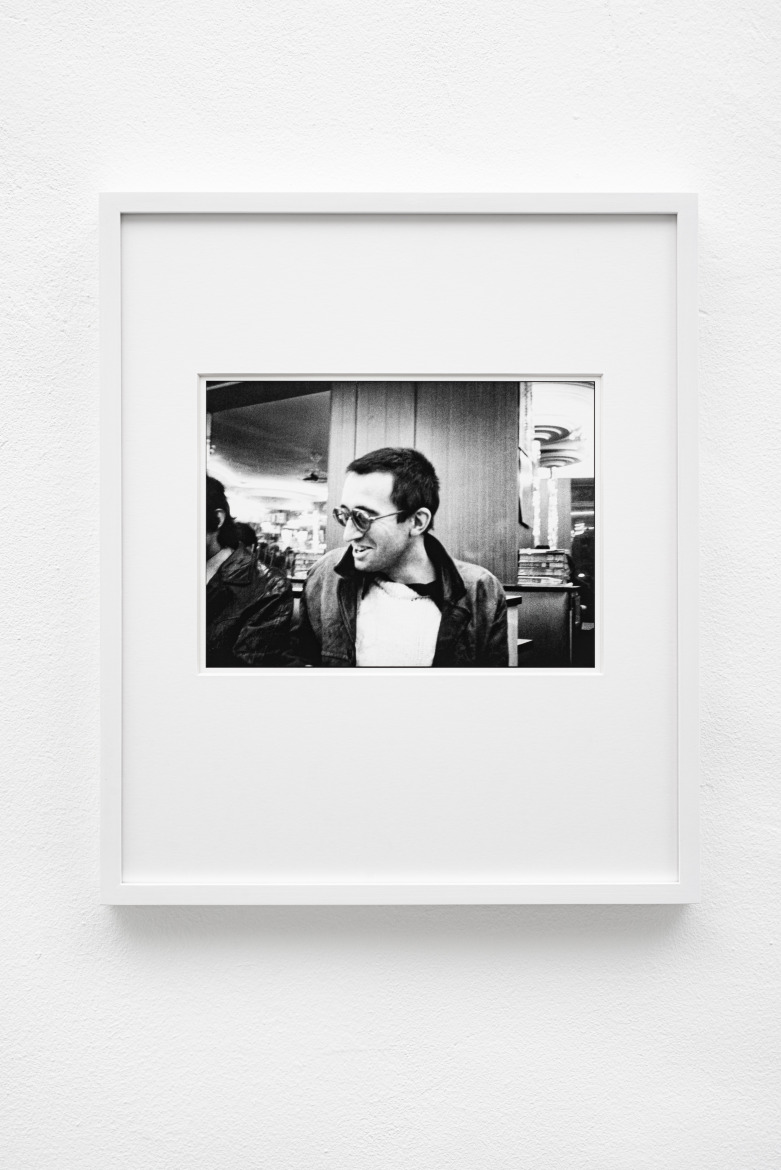

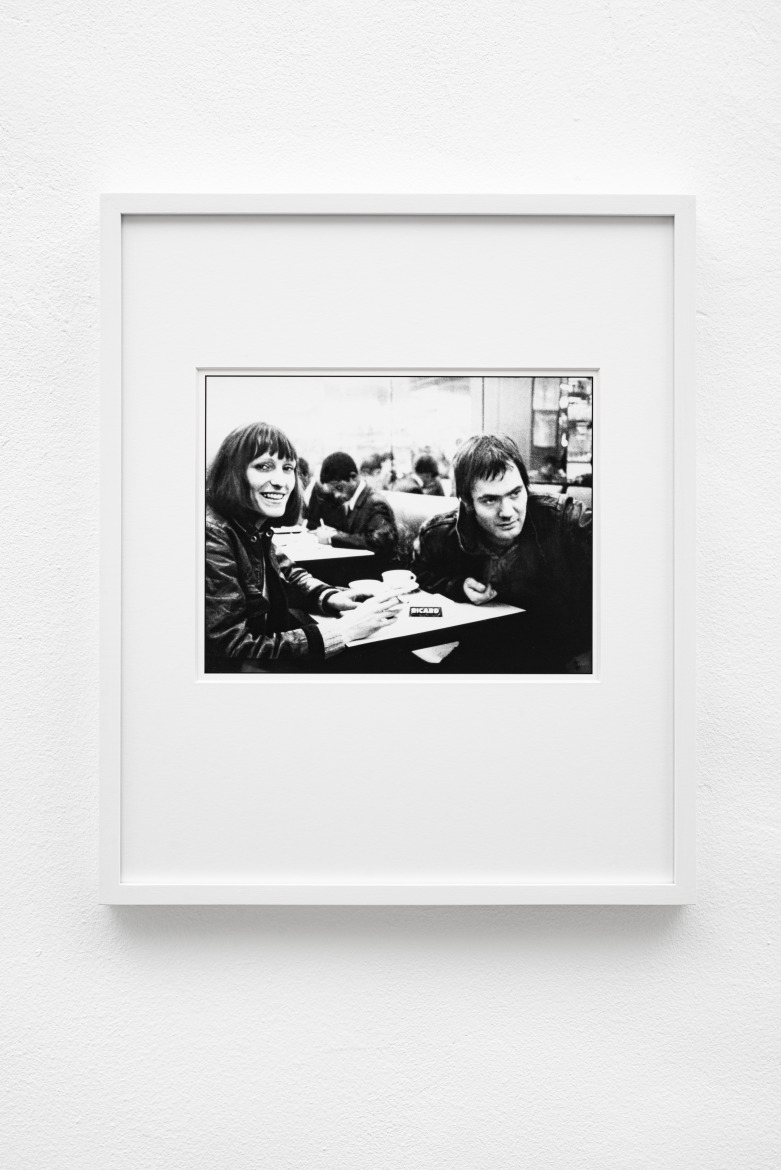

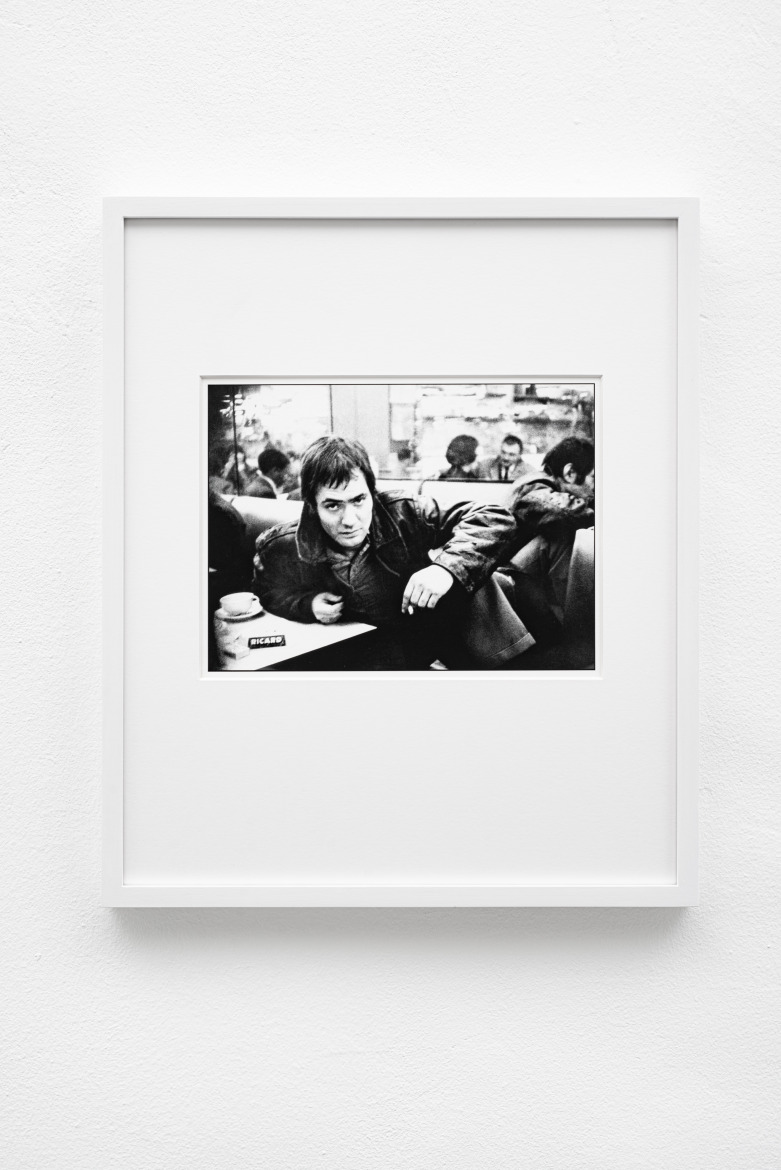

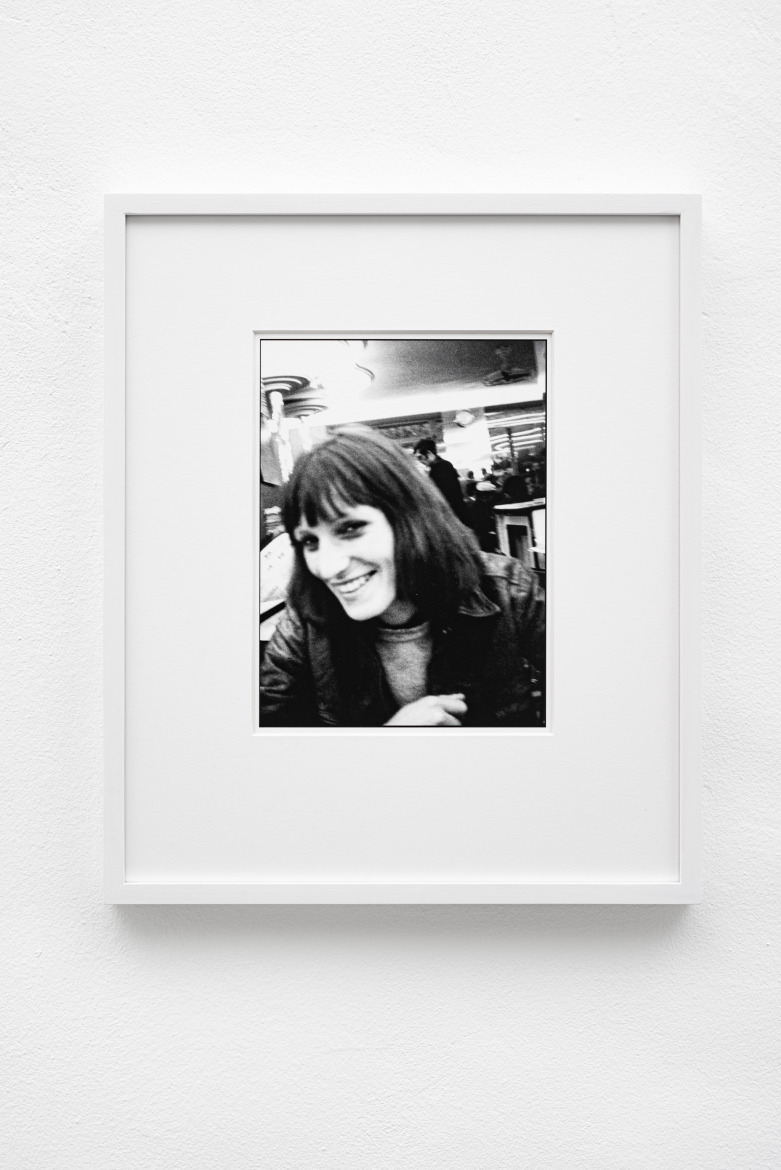

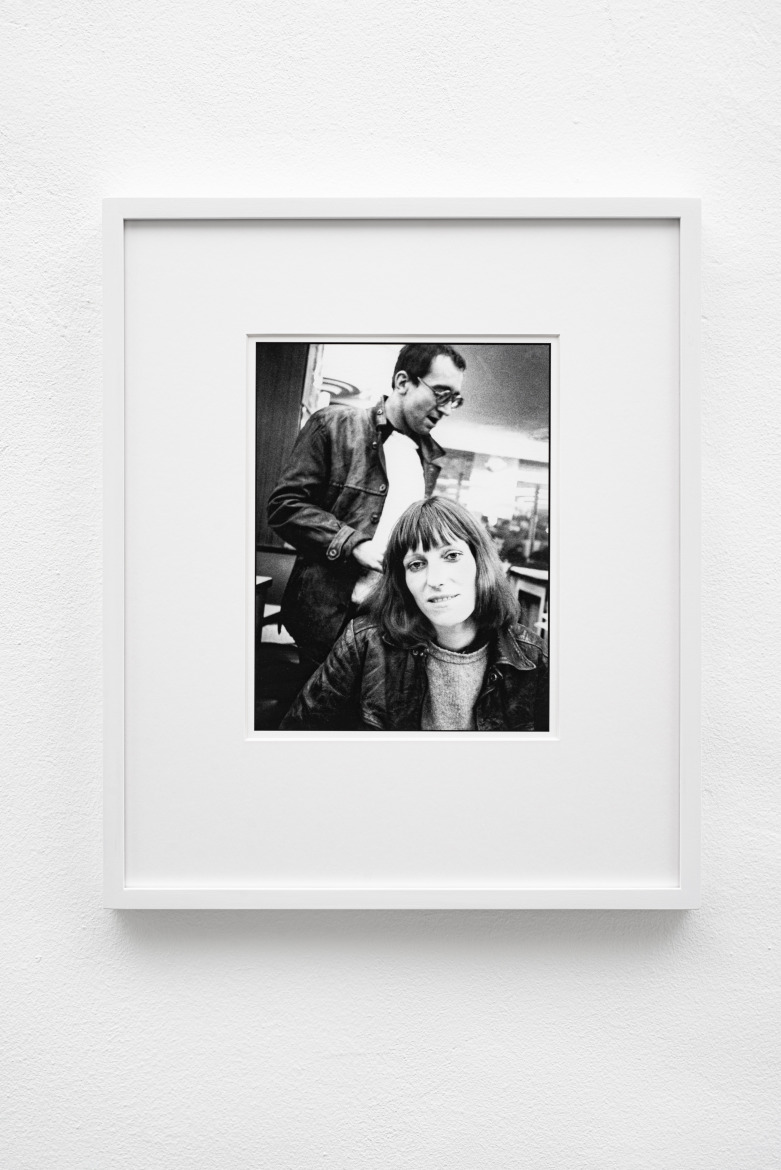

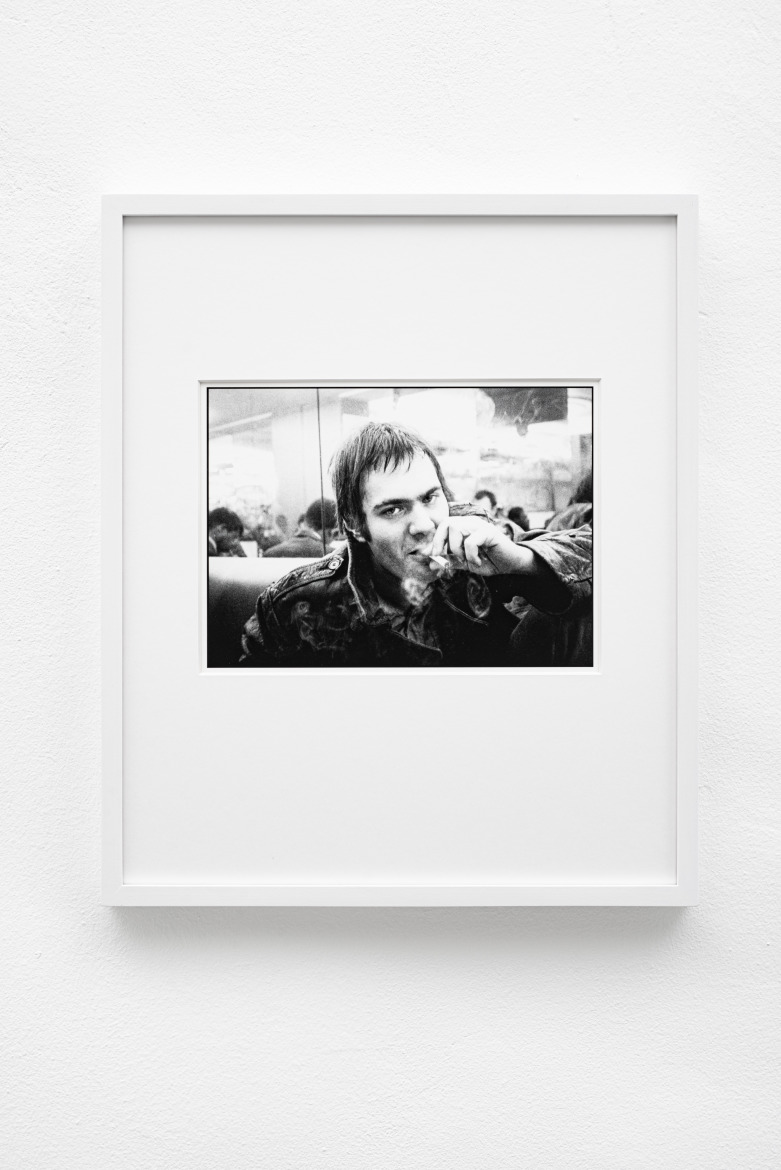

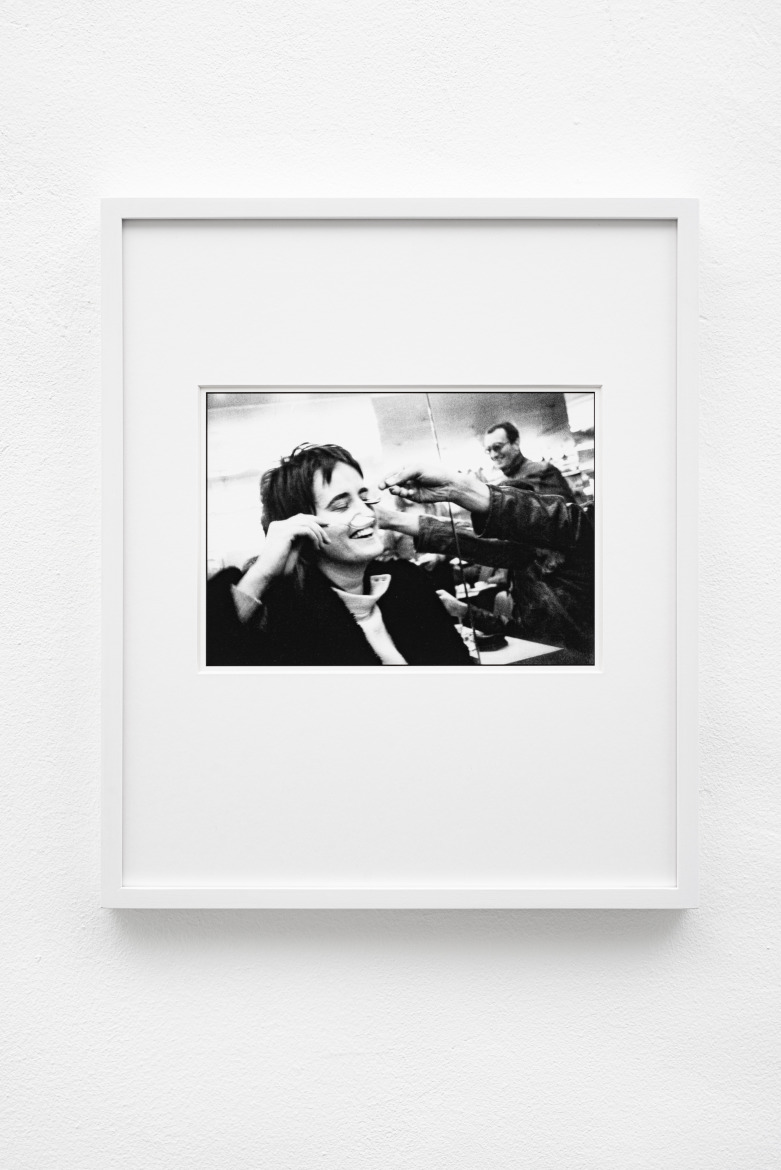

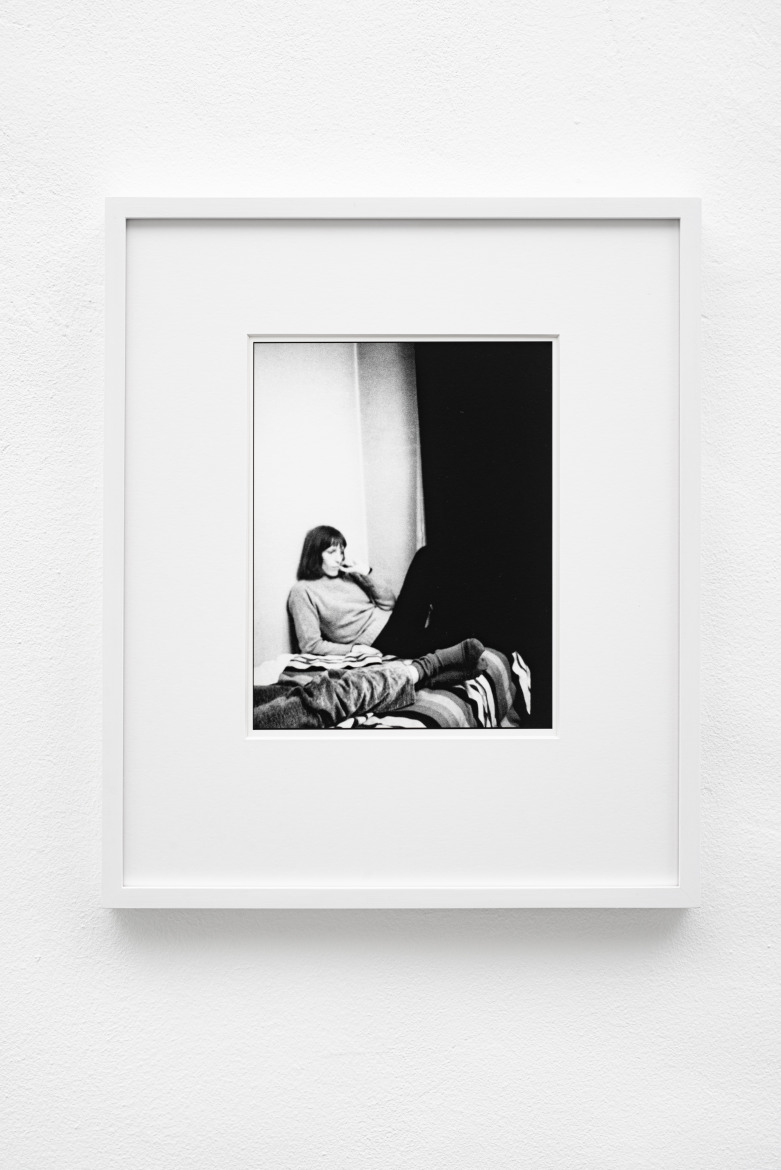

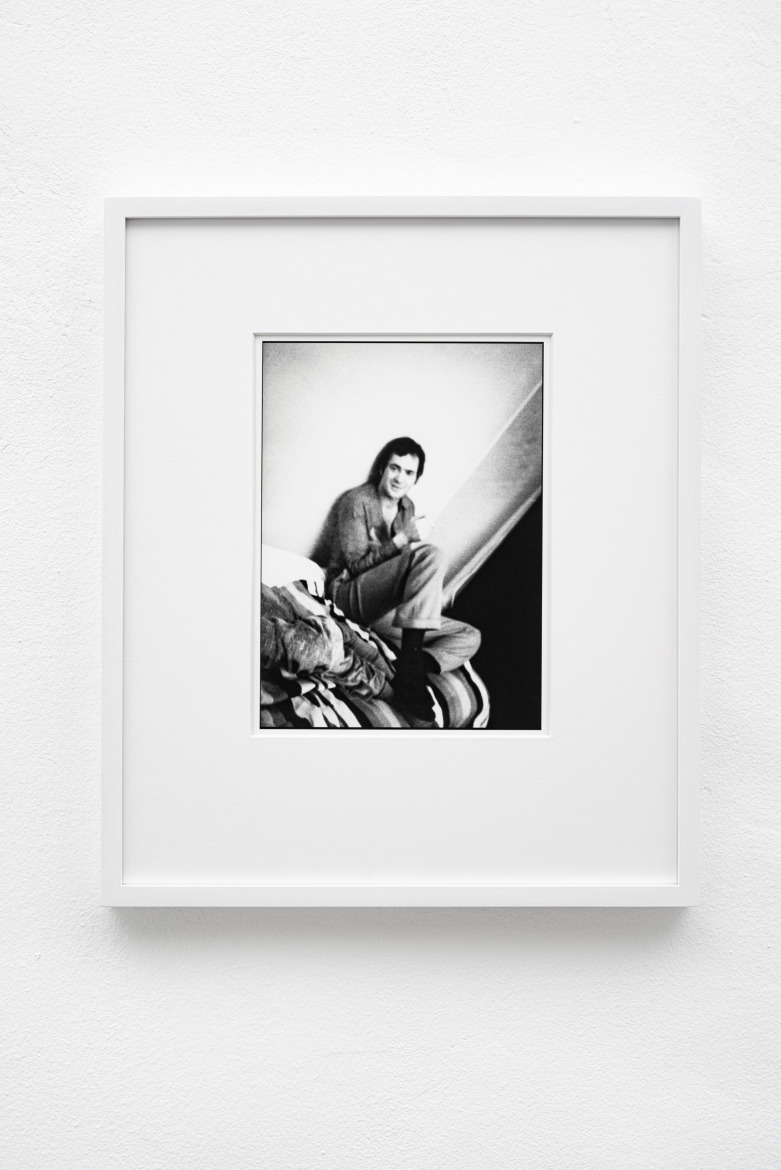

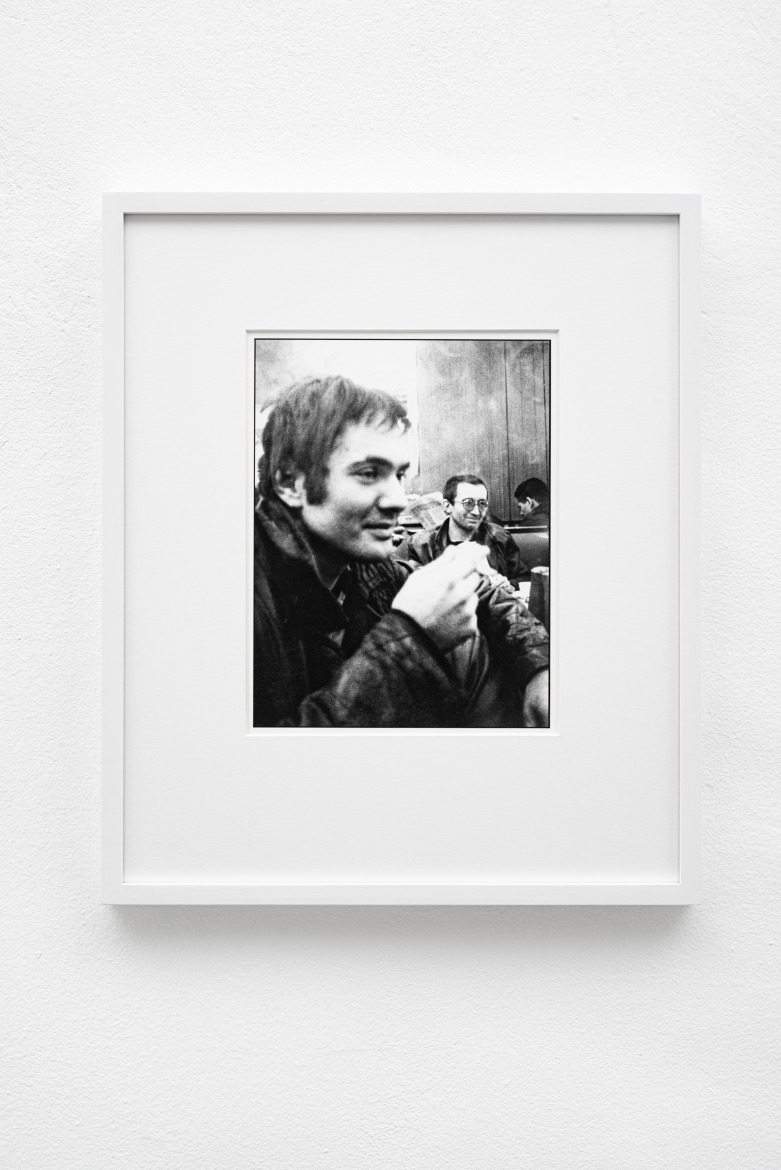

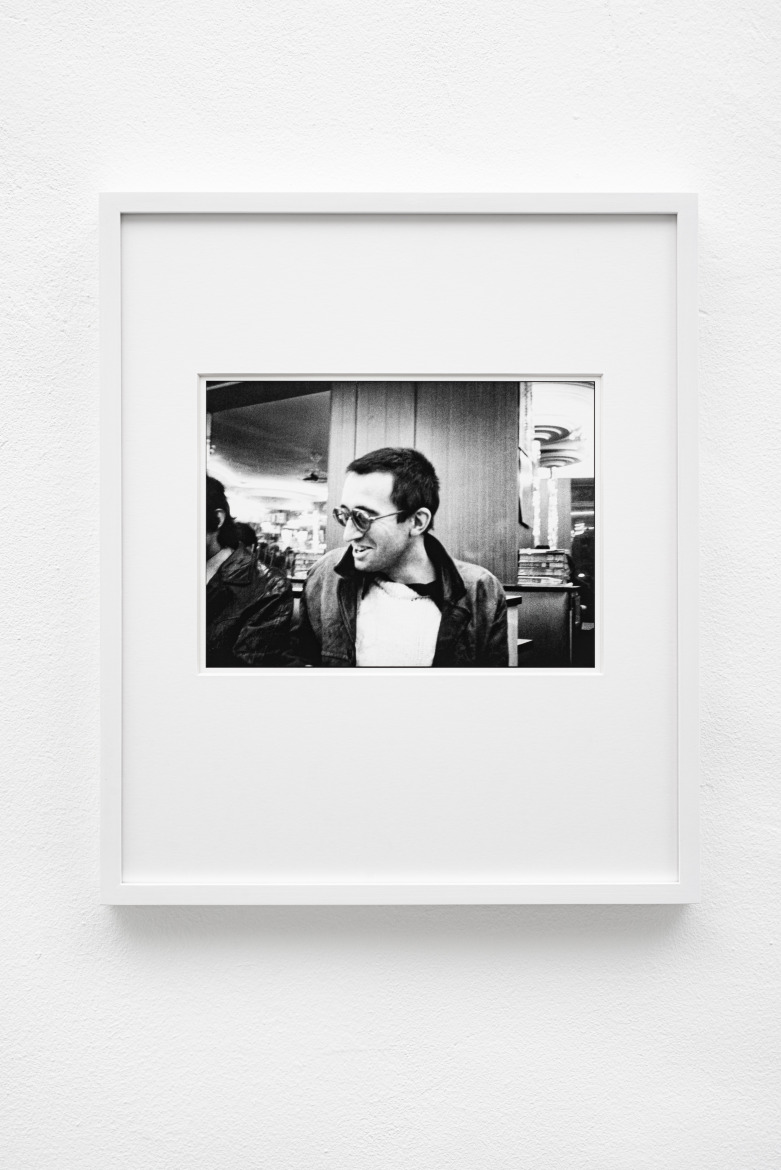

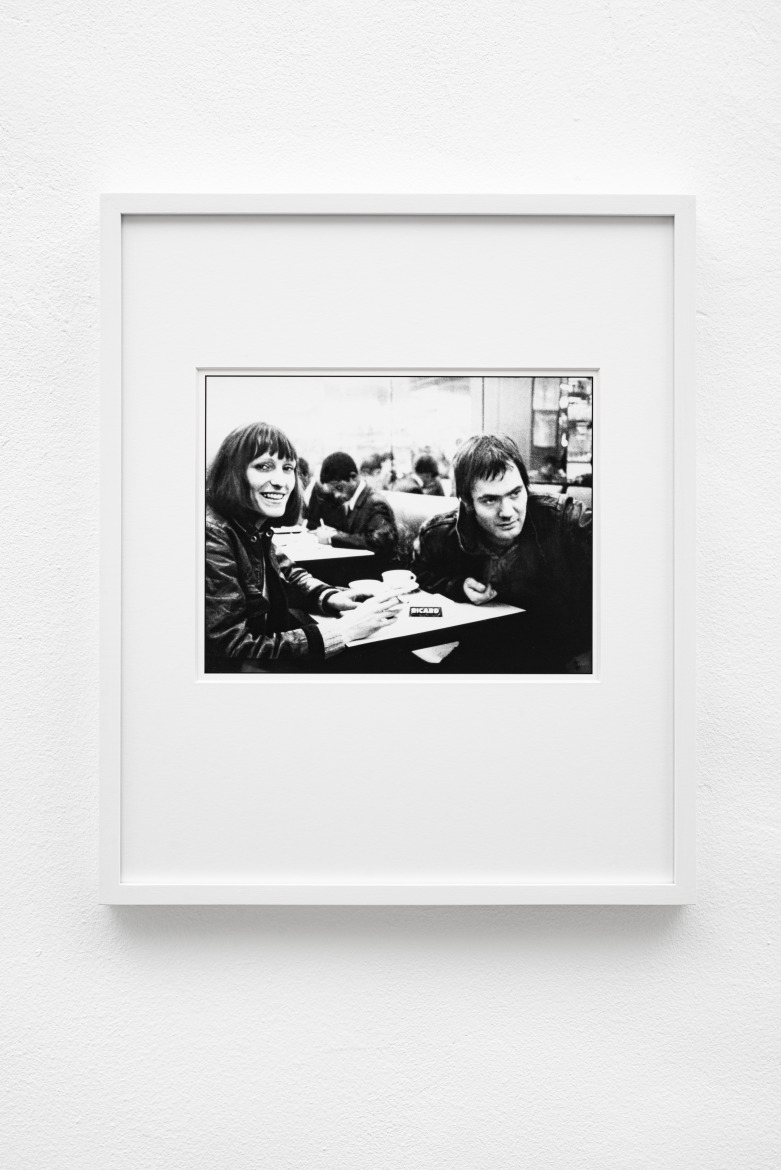

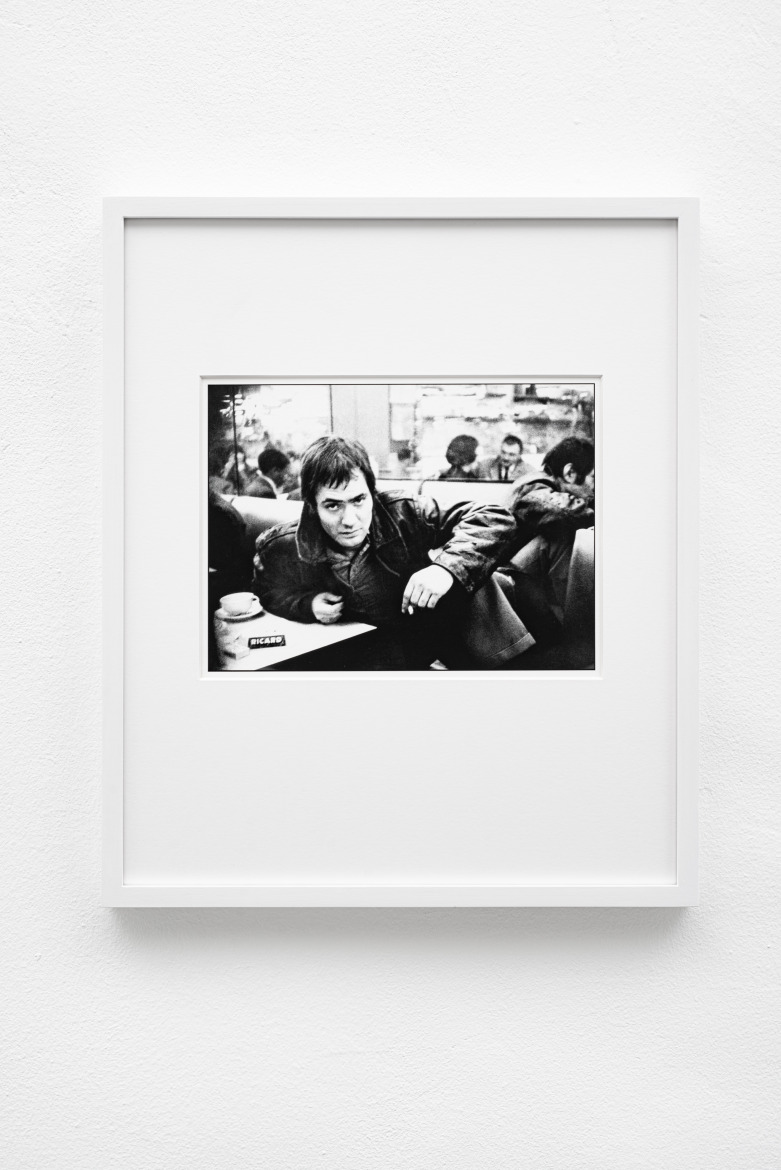

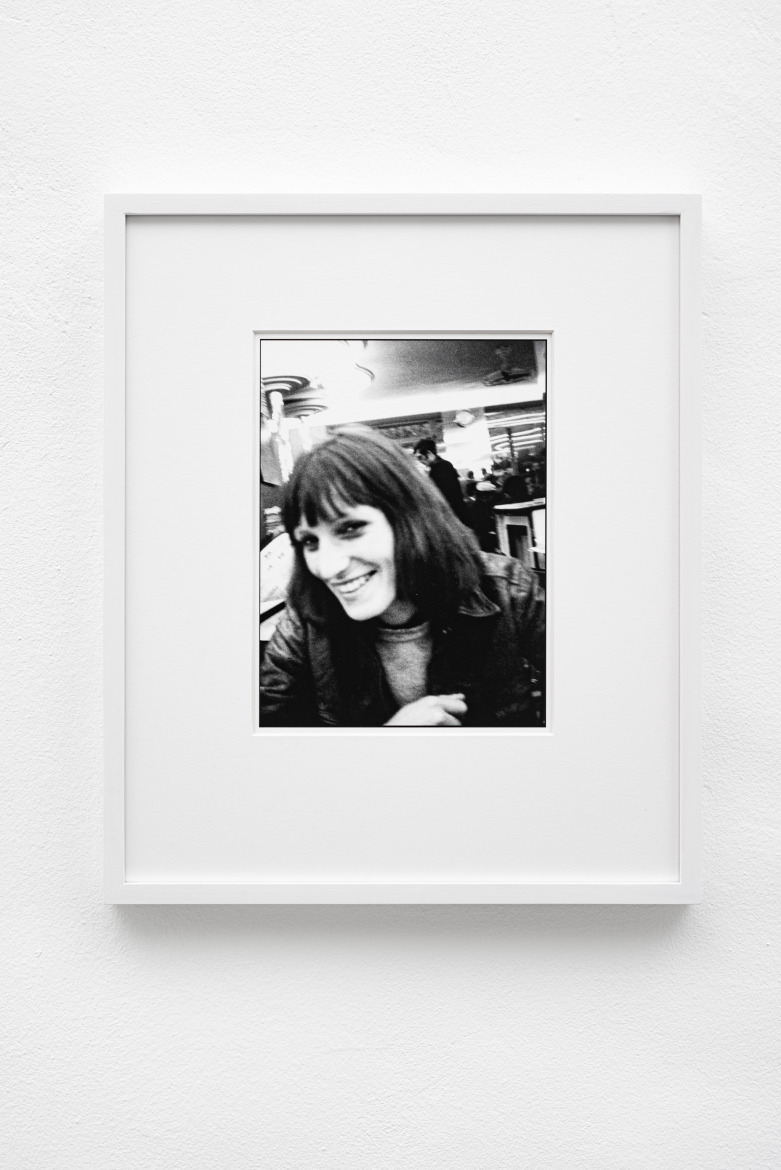

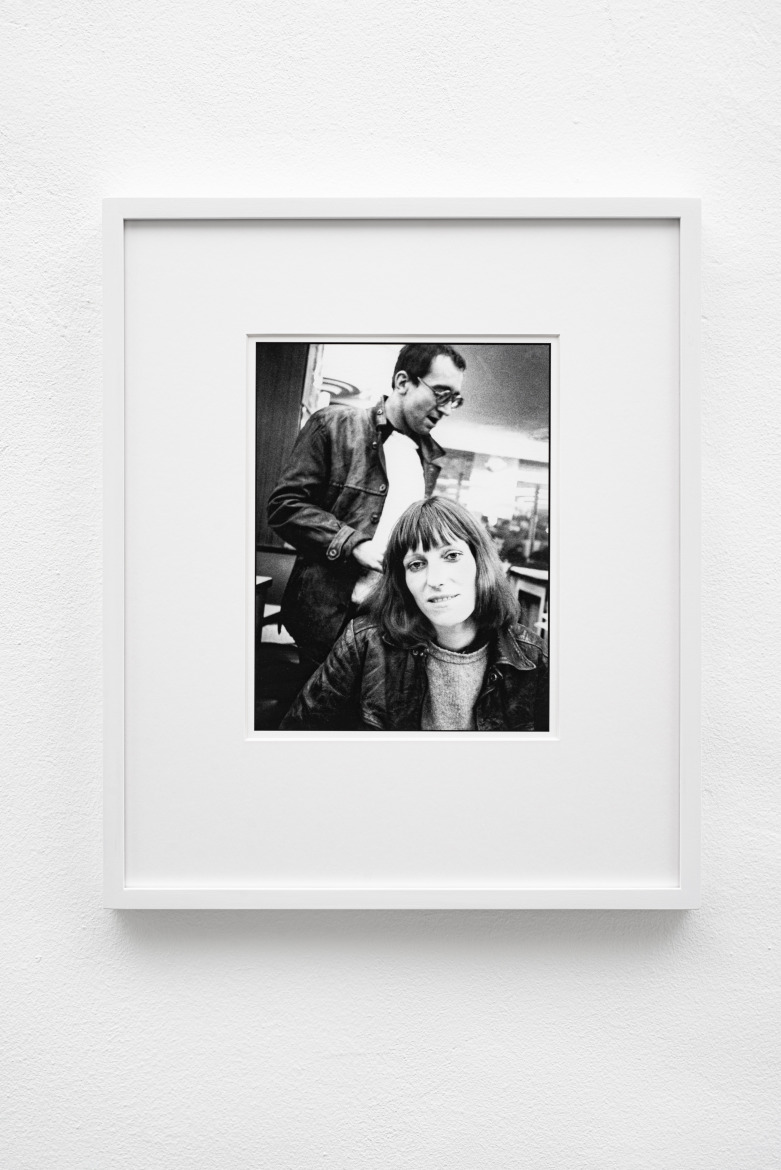

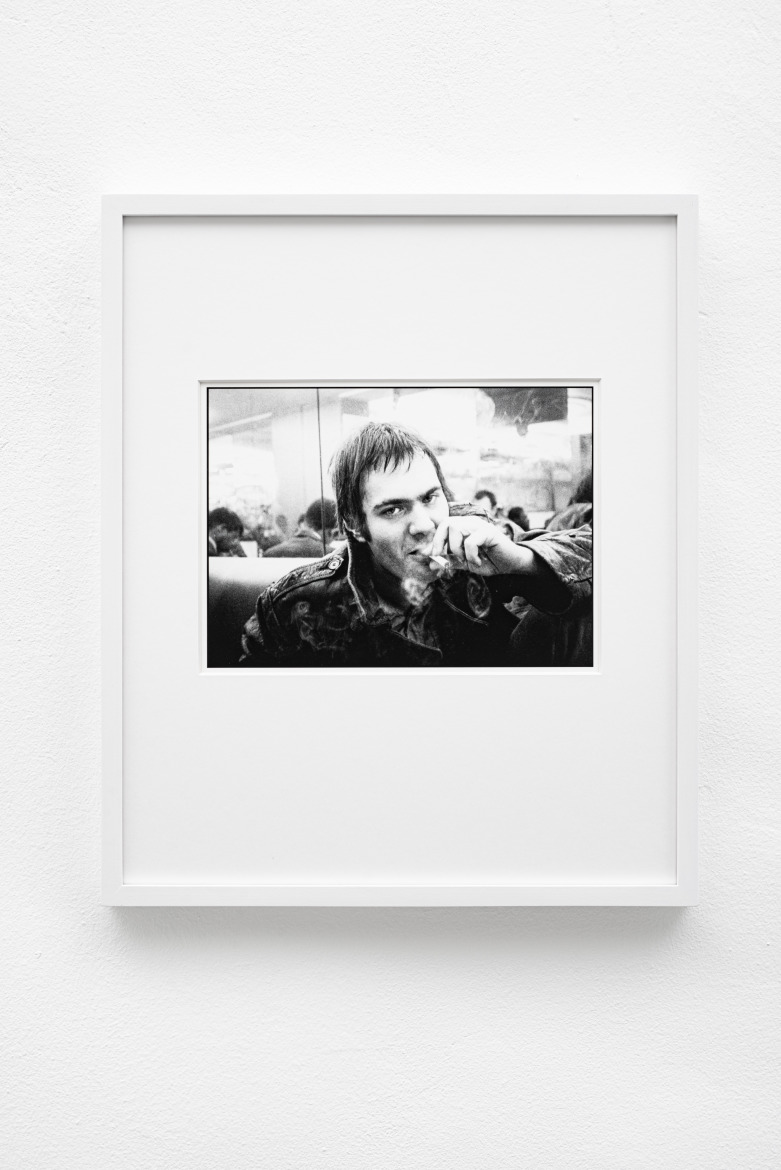

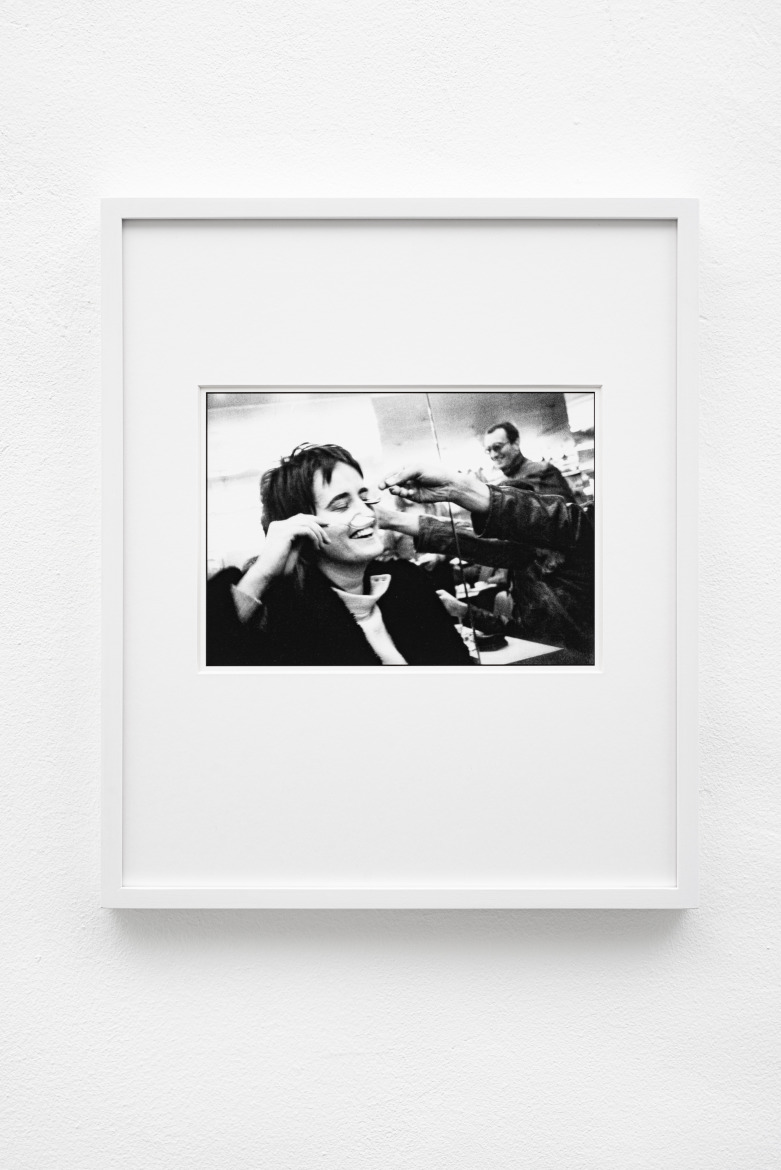

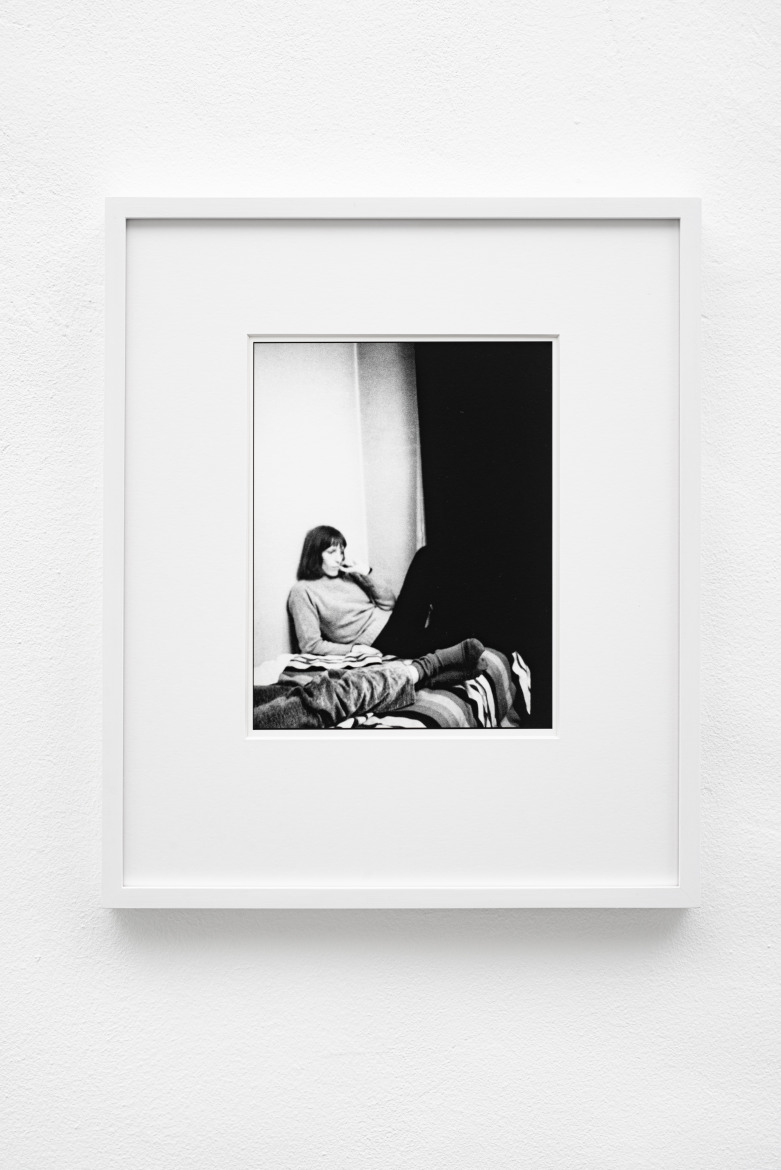

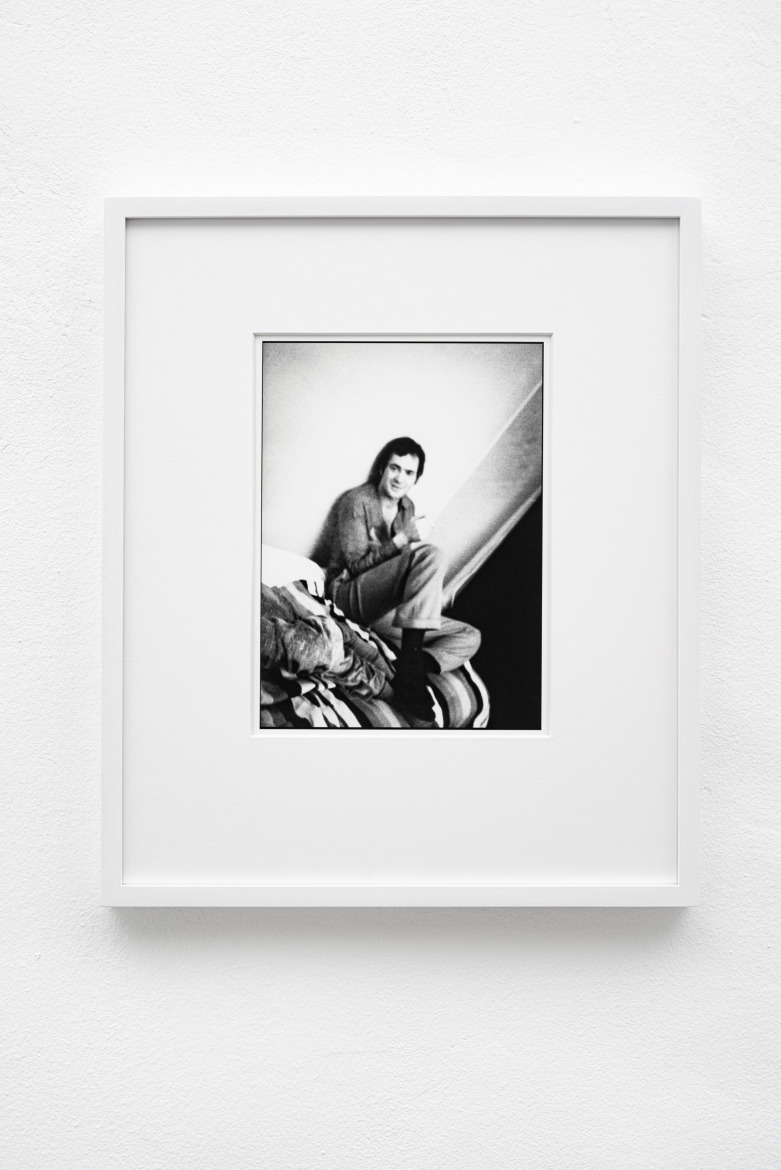

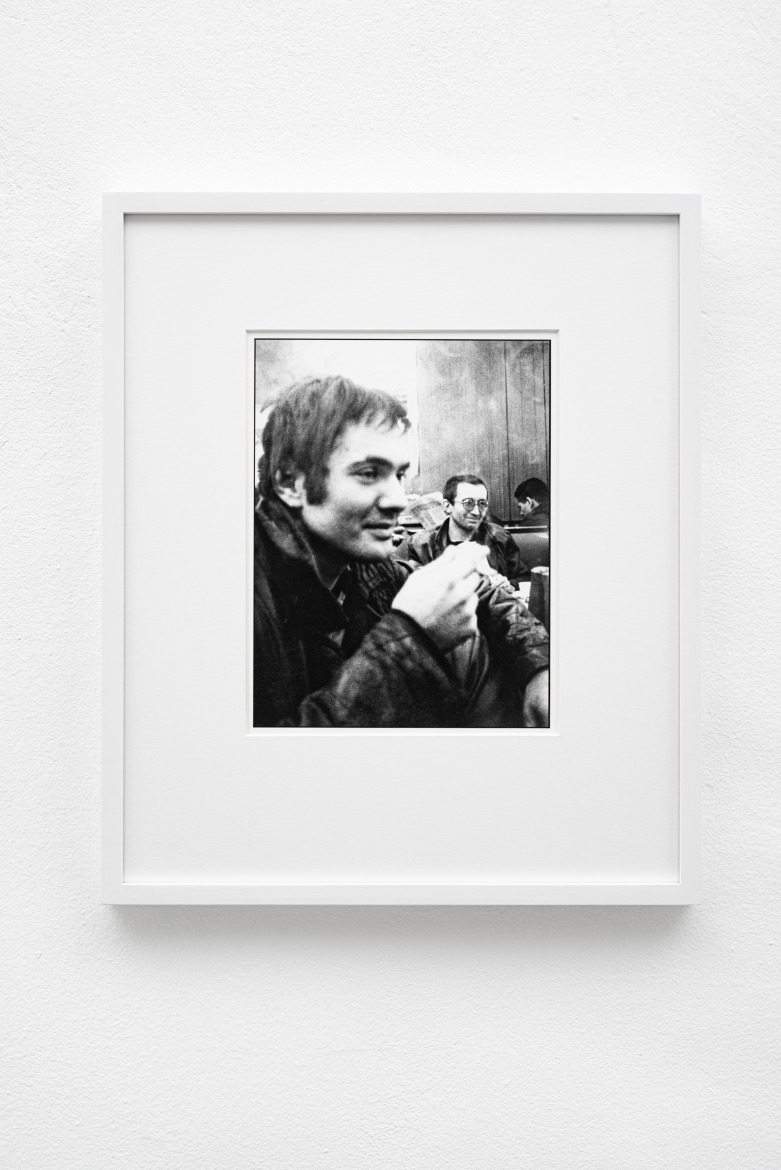

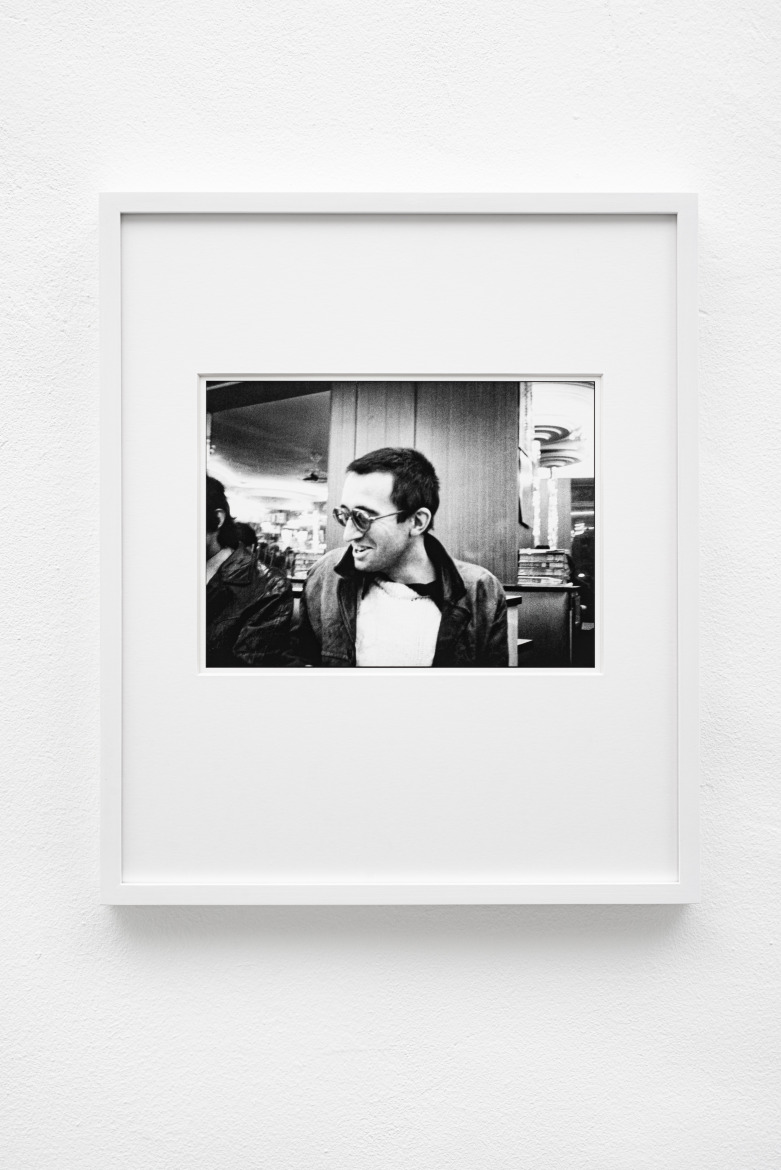

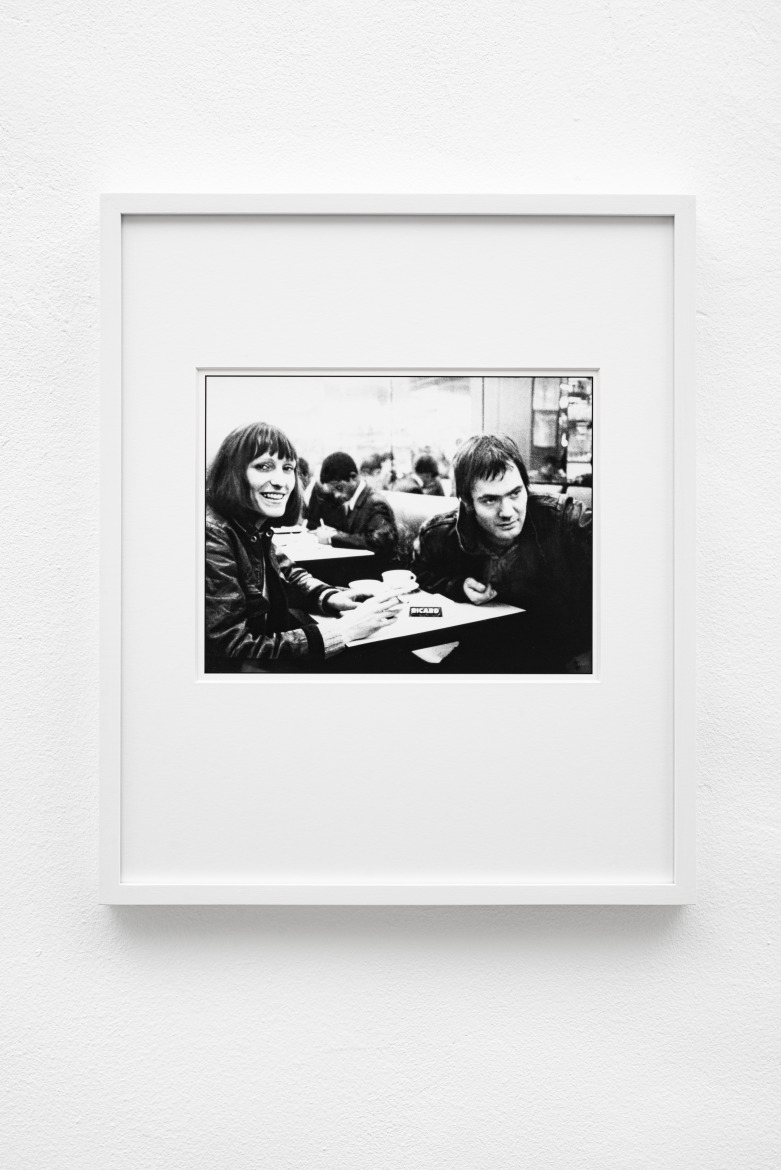

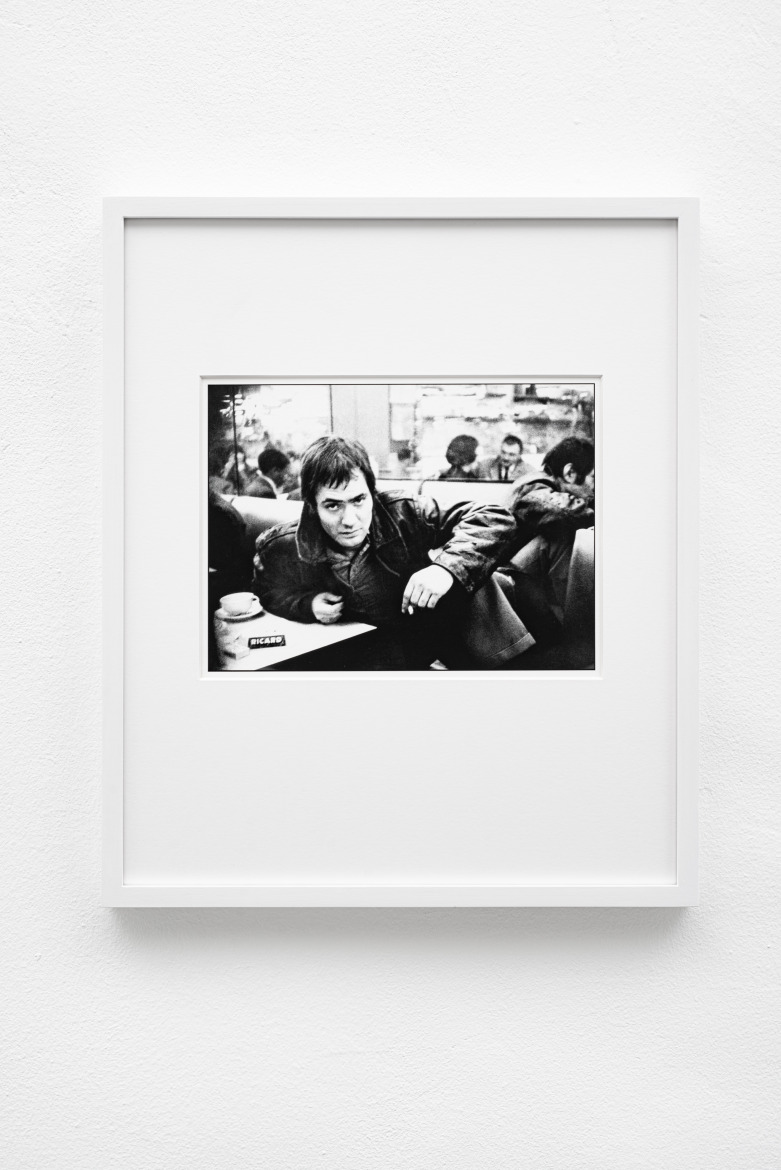

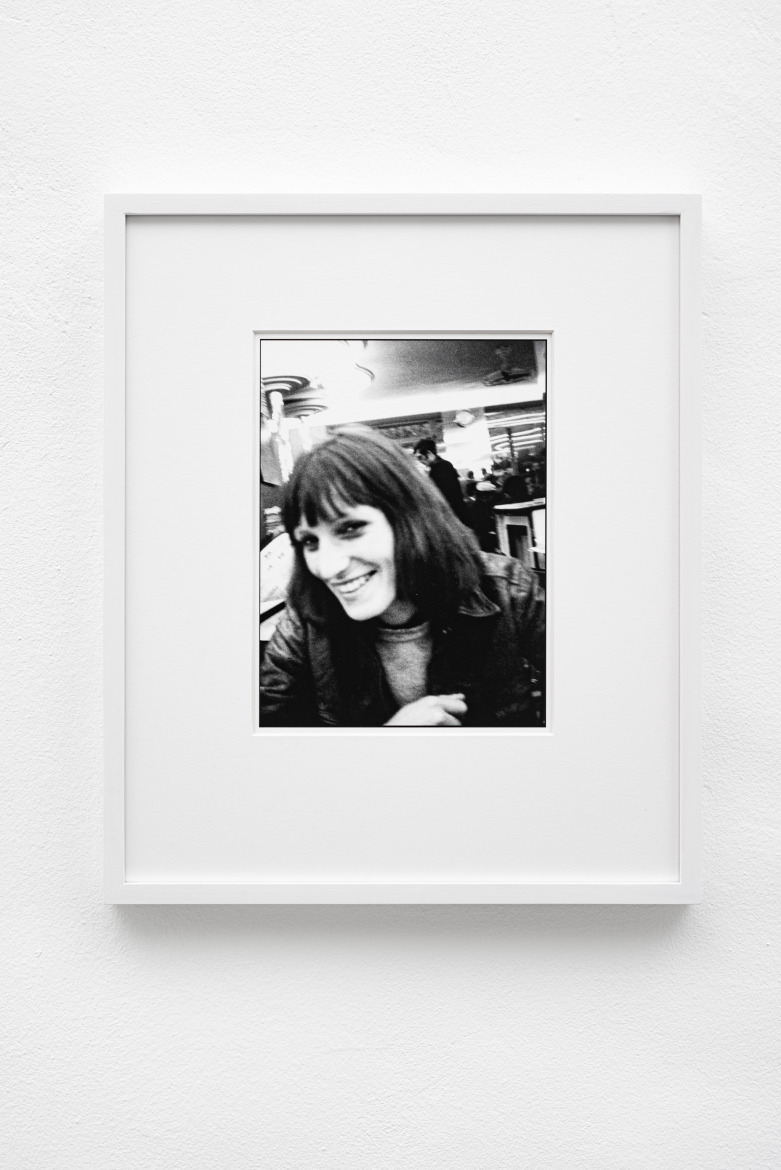

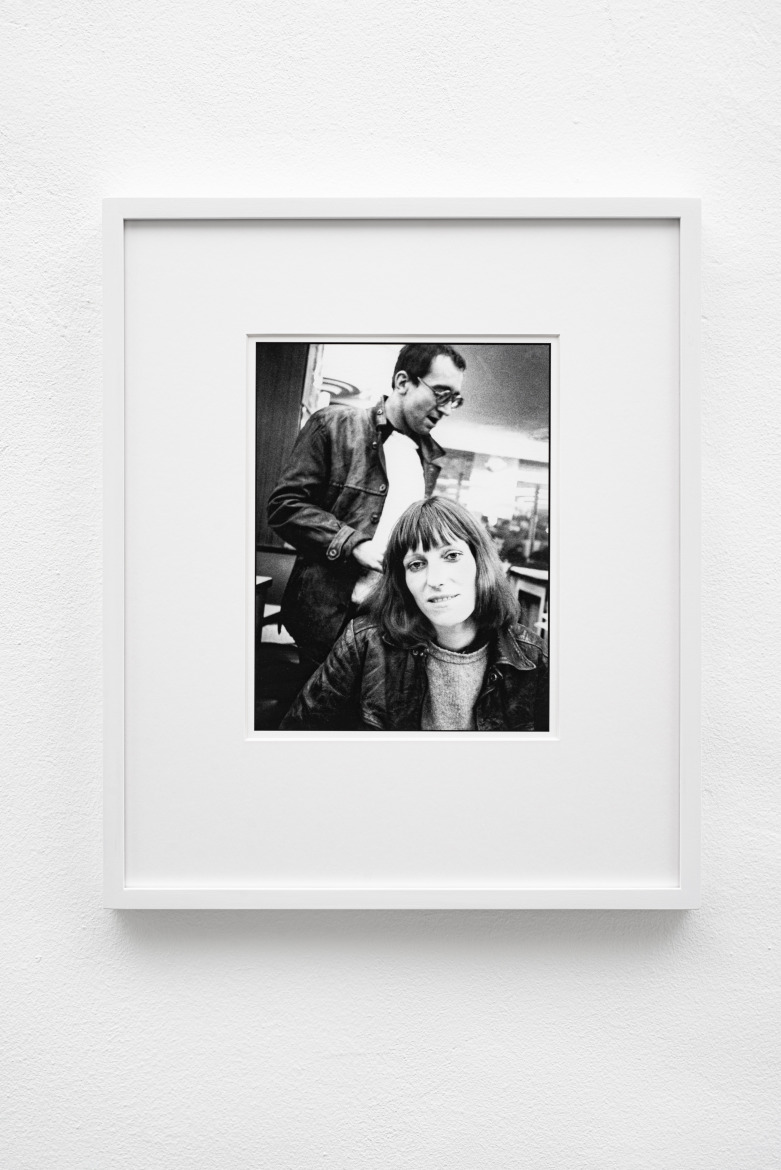

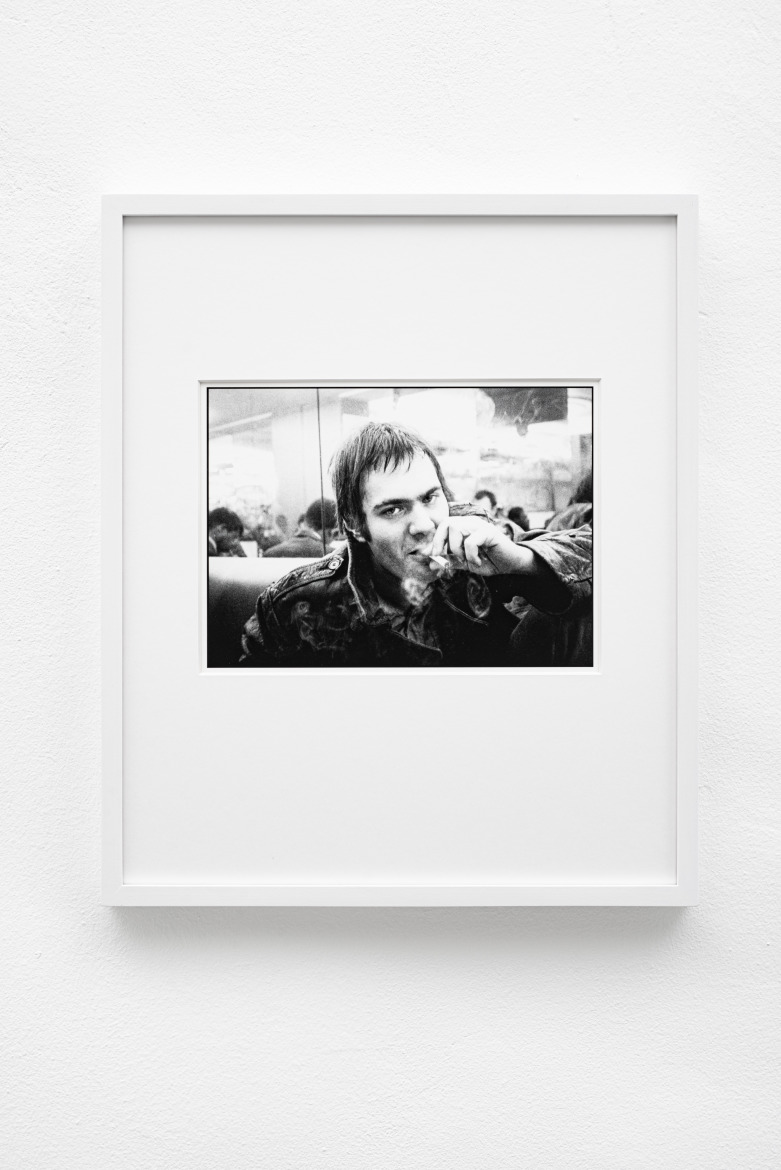

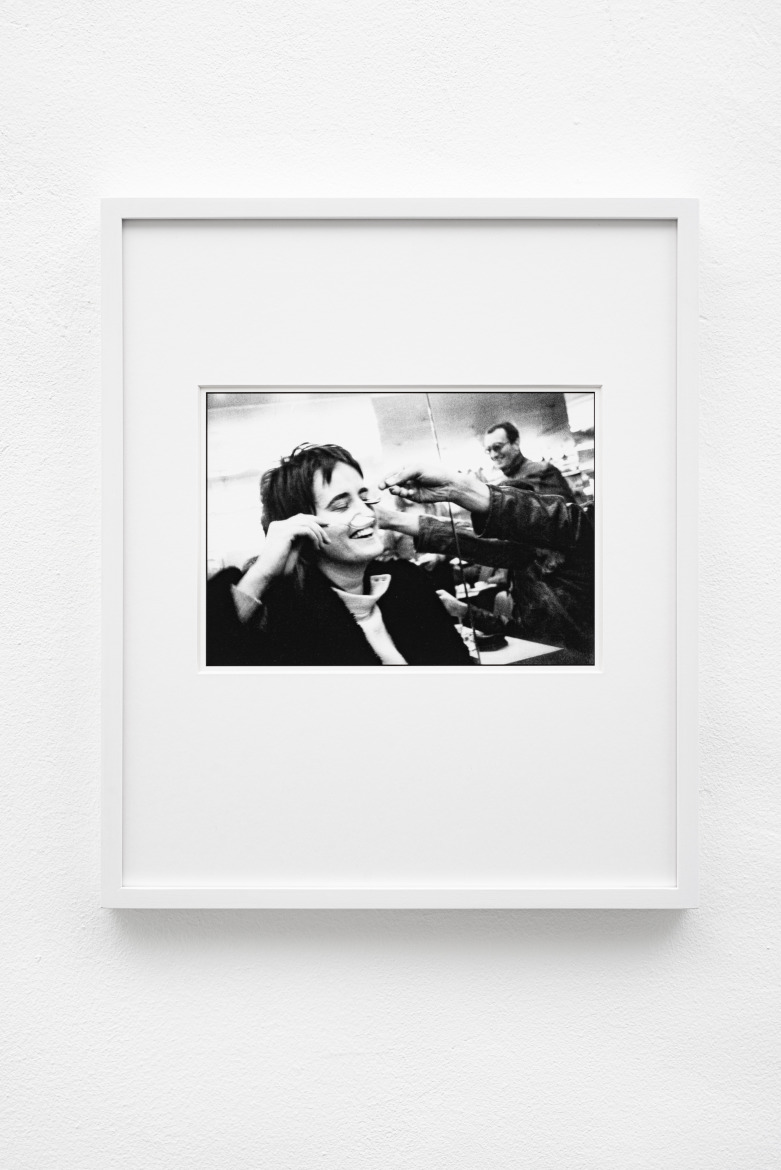

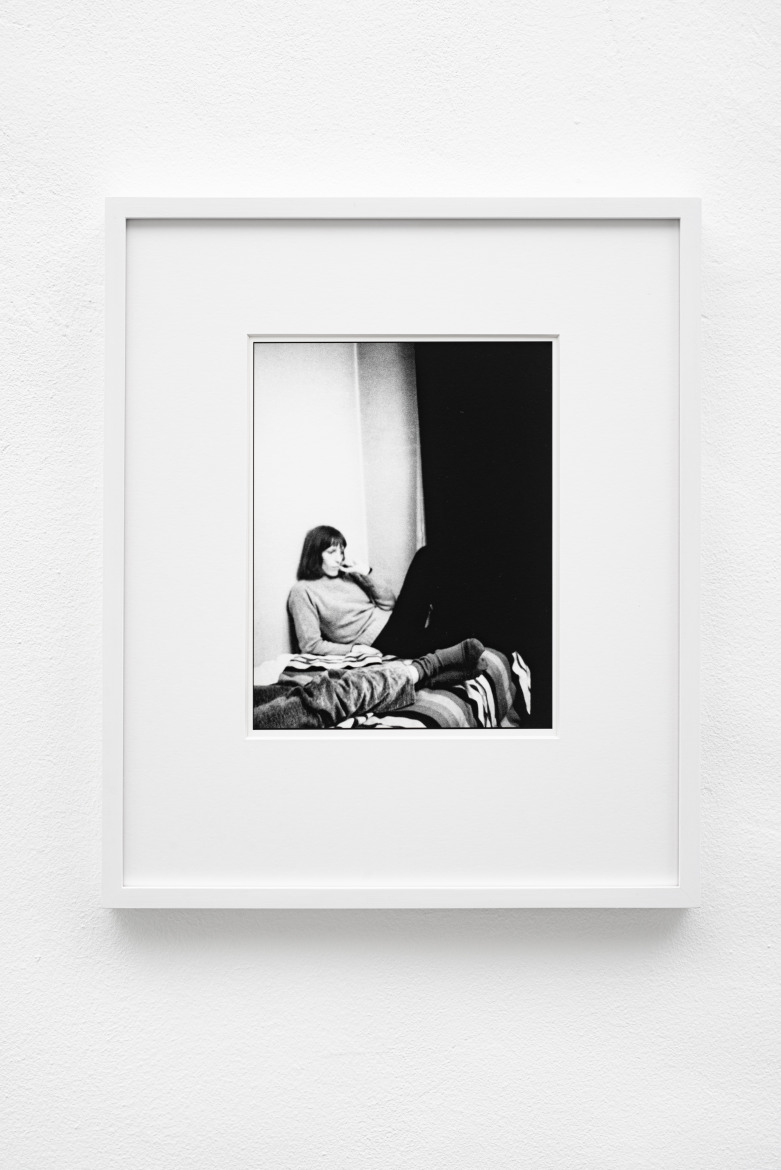

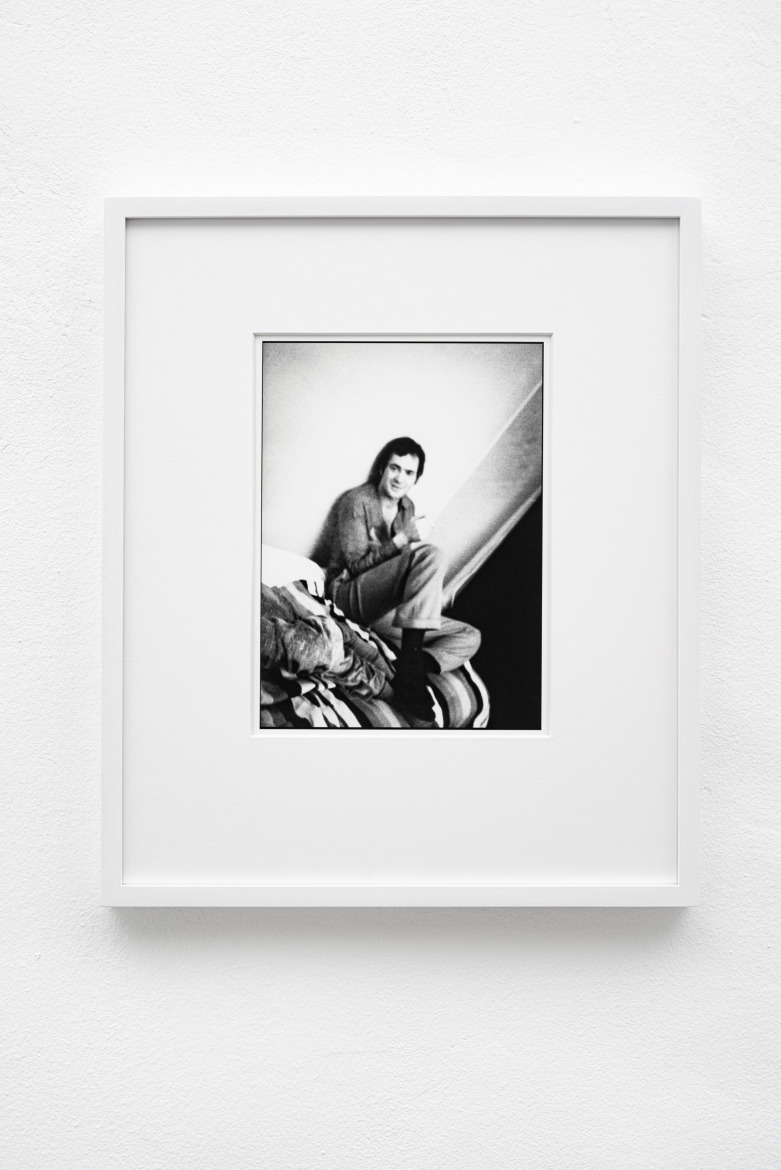

Photographed in black and white, mouth open, Astrid Proll laughs. Two hands appear from the edge of the frame pressing teaspoons to her closed eyes, feeding them, or threatening to scoop them out. Taken in a Paris Café in November 1969, the snapshot teeters on the edge of absurdity and violence. The boundary of pleasure and horror that in The Story of the Eye Georges Bataille defined as seductiveness. In this photograph and others taken of and by Proll in Paris, she and her companions including Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin are shown lying languidly or in animated conversation, they’re young and beautiful. These are not photos of the Red Army Faction; they are images of people who went on to form the RAF. Here, they still just about belong to the world of radical counterculture, and are not yet the property of the Federal Republic of Germany’s carceral system or the political imaginary of would-be revolutionaries.

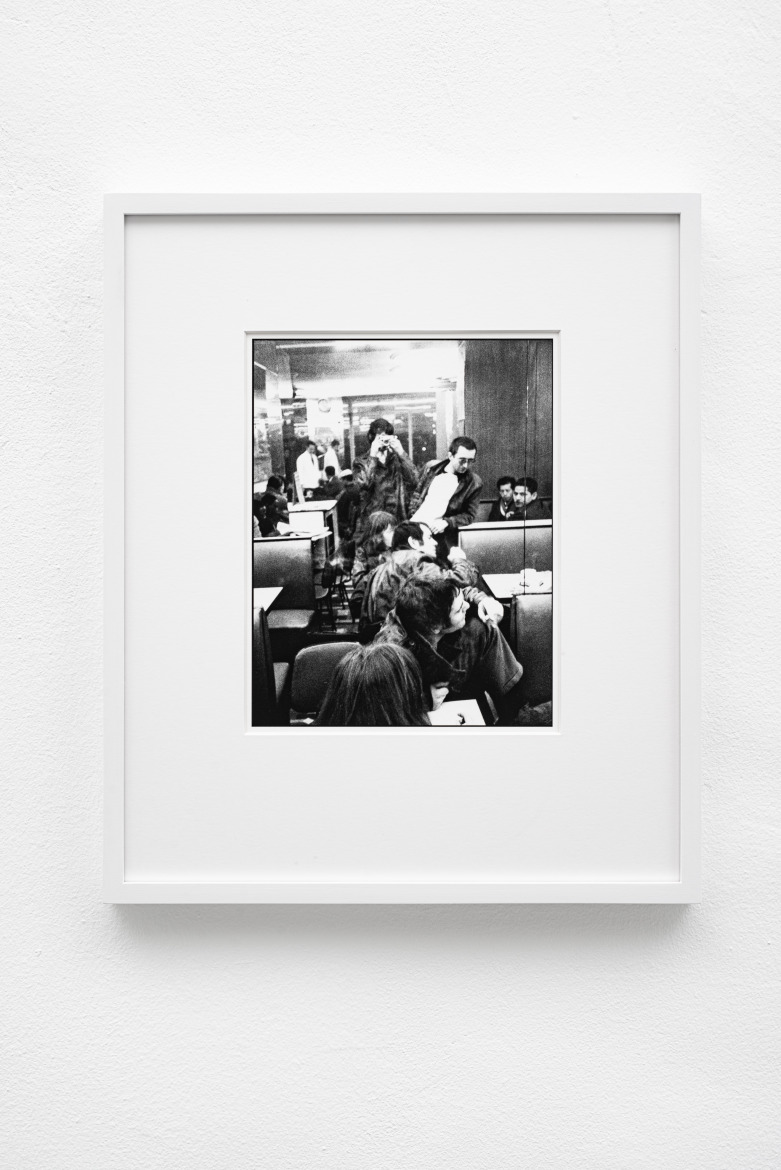

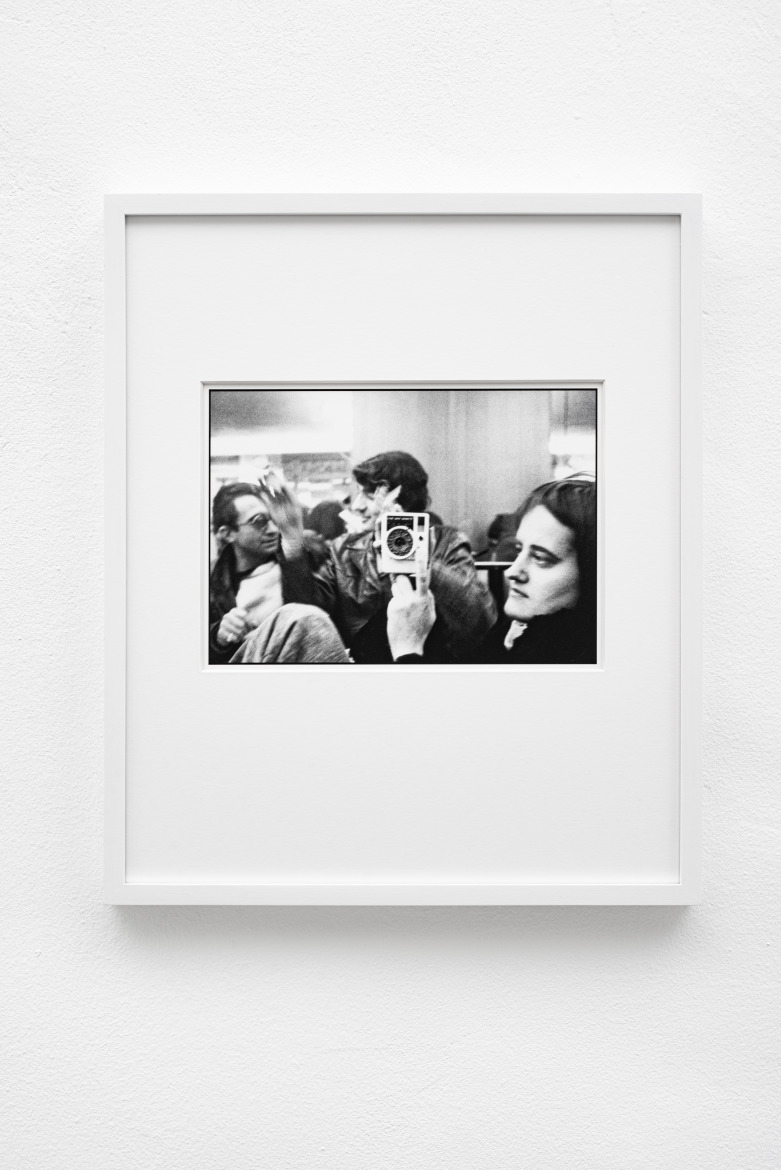

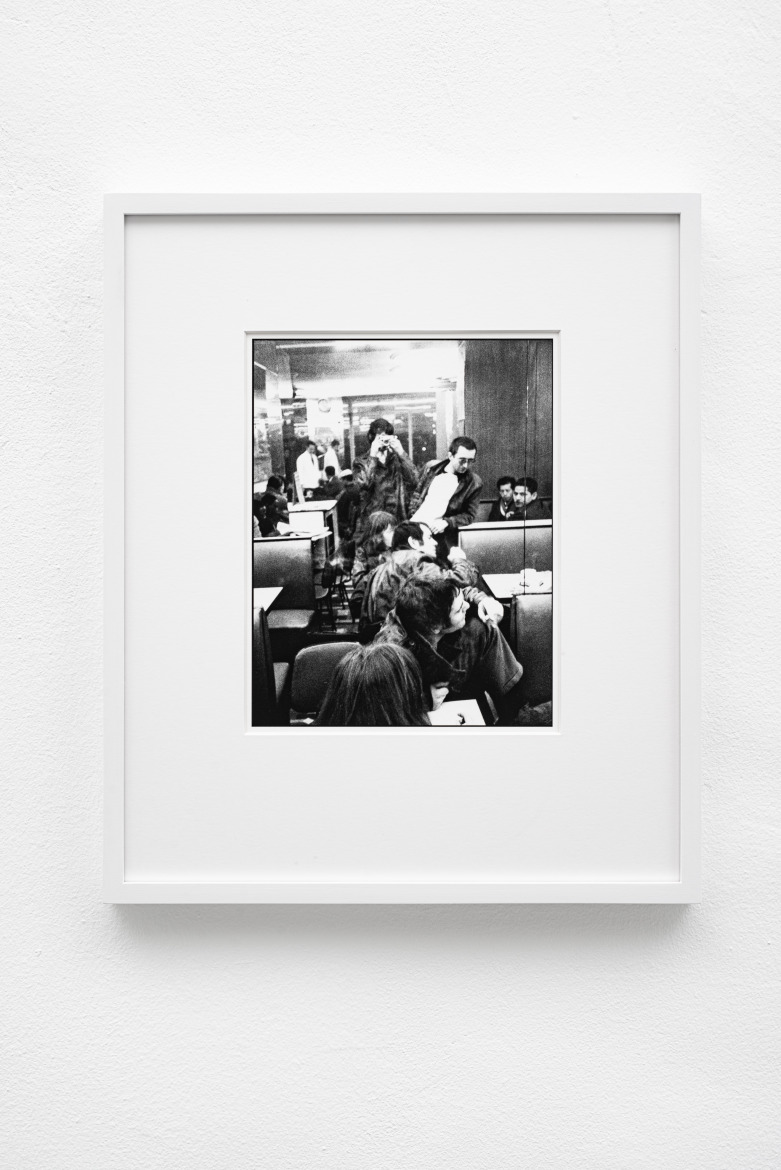

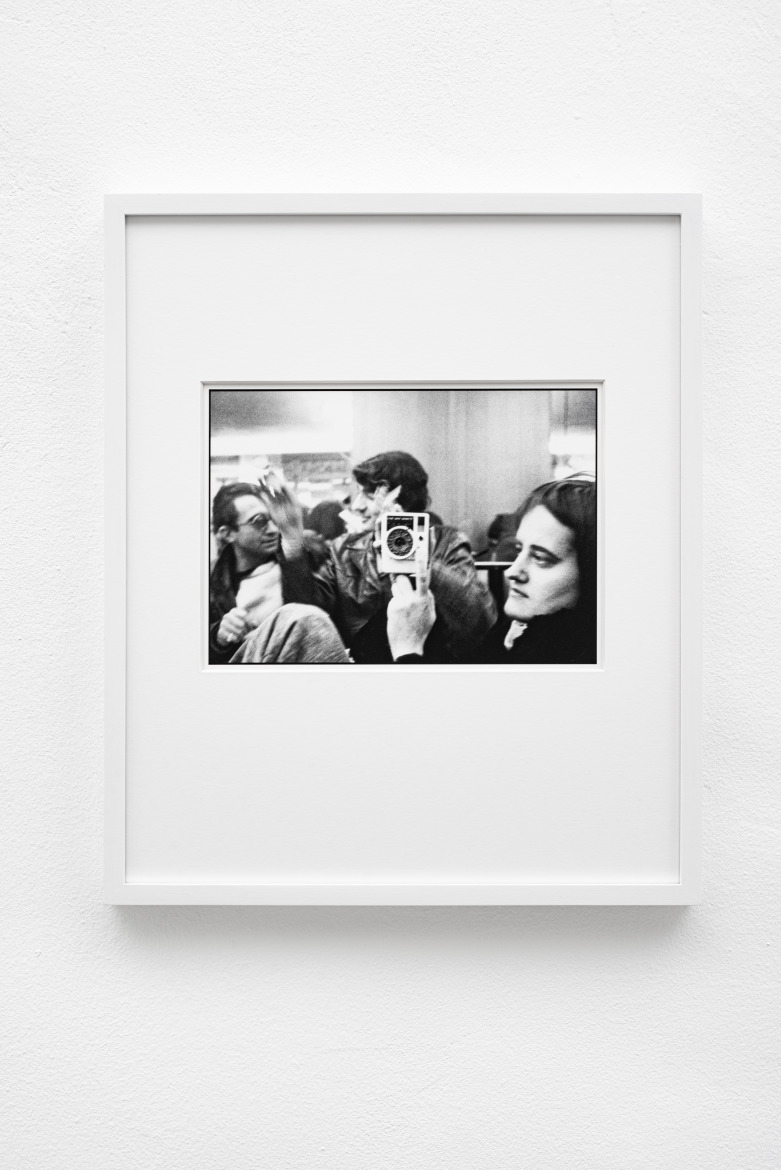

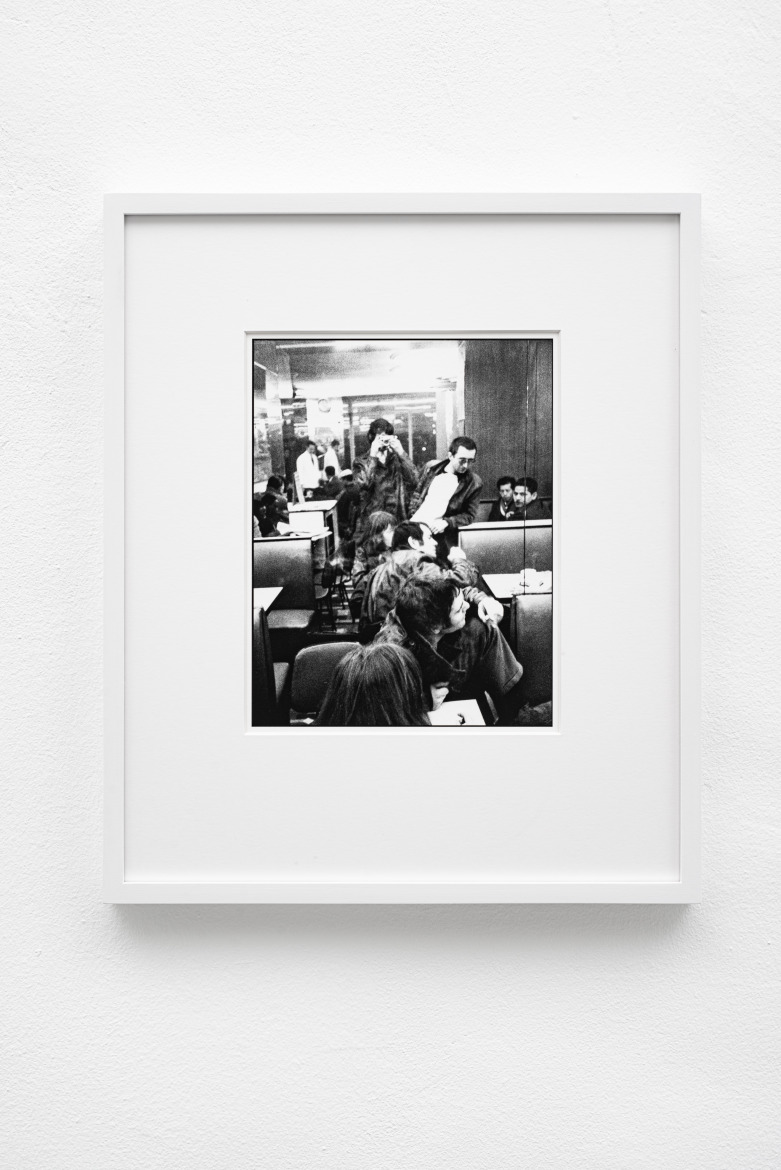

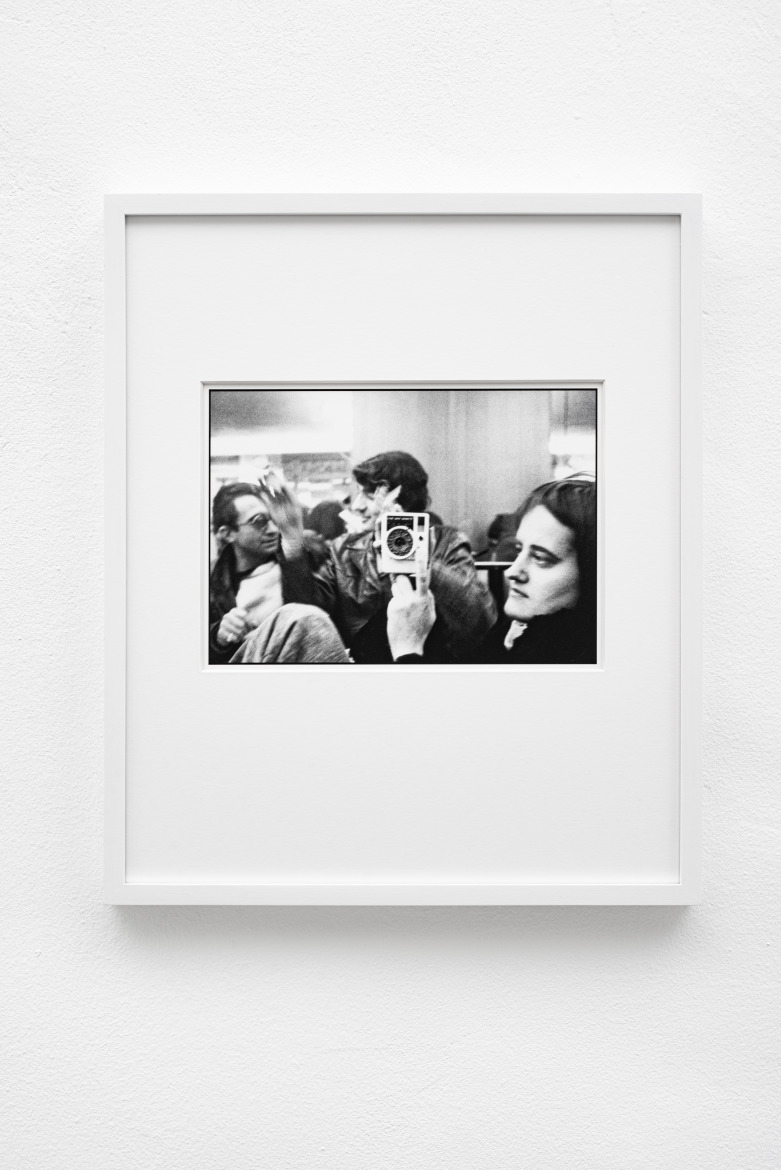

The photographs have the appearance of casually snapped pictures, taken by Proll, who had studied photography at Lette-Verein in Berlin, using a Canon Dial 35-2 – an unusual camera which shoots 18mm x 24mm half-frame images on regular 35mm film, producing a total of 72 images from a full-frame 36 negative film. However, the negatives that show the dynamic of these images are no longer in Proll’s possession. In the exhibition, the singular images are stilled, cut out from the dialectic motion of the two exposures, making each image, in its singularity, falsely iconic. But even when framed and behind glass on a gallery wall, looking at Proll in this photograph, you can almost hear the chatter of the café, the laughter of her peers, or the plop of an eye gouged from its socket.

Despite the claims made for photography’s immediate and indexical nature it is not a punctual medium. The photograph is always attached to other institutions which frame, define, and mediate the image. In a picture album or on a mantel piece photographs belong to the domestic and the personal sphere, in a magazine to mass culture, in a gallery to the art market, or on a wanted poster to the police. Publication schedules, archive access, generalised interest or disinterest, drag and retract images from visibility. The genealogy of the distribution and reproduction of Proll’s Paris photographs is characterised by a stuttering latency, and at some point in the early 1970s the story of the Paris photo splits from Proll’s own.

Following Proll’s participation in the freeing of Baader from police custody in 1971, and a time spent on the run, her own relationship to photography became even more fraught. The camera could betray, a photograph could lead to identification and arrest. In the early 1970s Stern magazine bought the negatives. In the following years, these images were widely publicised by the magazine and other publications. The most frequently reproduced photographs were of Baader and Ensslin, often these images were cropped to show them individually and not as a couple.

After a a period of incarceration which included sensorial depravation in solitary confinement, Proll escaped Germany and lived underground in London from 1974-1978. Re-arrested in 1978 and awaiting extradition, friends she had made in the left-wing counter-cultural circles in London organised an independent media campaign to protest her deportation. In the same year Stern interviewed Proll, portraying her case in a sympathetic light. Released from German prison in 1981, Proll studied film in Hamburg and eventually went on to work as a picture editor for the cultural and lifestyle magazine Tempo.

Eventually, in 1998 Proll published Baader Meinhof: Pictures on the Run ’67-77 with both Steidl and Scalo Press. This publication included the Paris photos alongside other images taken by arresting police officers, and newspaper journalists. Printed as a coffee table style publication, with a red-for-revolution cover and design scheme, these photographs run across various registers and categories of documentary photography. The book features photographs of kidnap victims, crime scenes, dead bodies, and graves. A portrait of Ulrike Meinhof in sunglasses reads as fashion editorial, while side-by-side police portraits of Horst Mahler – in one his bald head covered by a wig, in the other with it removed– are documents of juridical realism. Following the publication of Pictures on the Run, Dazed and Confused magazine ran an editorial review and organised an exhibition presenting the book and a selection of the photographs in their gallery. Since 1998 Pictures on the Run has been republished twice.

Thirty years on from Proll’s trip to Paris, what did the protests and the crimes of the RAF mean to the readers of Dazed and Confused? Twenty-five years on from that exhibition what does the RAF mean today? When Stern interviewed Proll in 1978, after the violence of German Autumn of 1977, Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, Holger Meins and Jan-Carl Raspe were dead. The Stern feature, along with the volume of grass-roots protest literature published in London, including ‘The Friends of Astrid Proll’ pamphlets, and a cover-story on Peace News, decried the state apparatus of the German Federal Republic. An op-ed in Peace News states “The West German government have accepted that she is not a “terrorist” yet they seem determined to destroy her life here at least, if not destroy her completely.”2 The Dazed and Confused article opens by contextualising the historical images within modern terrorism “A few months ago, the Labour government passed the most draconian anti-terrorist legislation ever seen in this country. Bombs explode in Nairobi, Dar-es-Salaam and Cape Town, and Astrid Proll published a collection of photographs titled Baader Meinhof: Pictures on the Run.” It’s difficult to perceive terrorists of today- Islamic fundamentalists or aged Irish republicans- as being in touch with youth culture, yet for a short period in the 1960s and 1970s a number of self-mythologised urban guerrillas spoke directly to an unfocused, nascent rebellion, bubbling within the children of the western world.”3 Despite her friends’ fears Proll survived her prison sentence in Germany, and unlike her former comrades she lived long enough to work in re-unified Germany, return to Britain, and be featured in a fashion magazine.

Dazed and Confused is one of the most successful British cultural magazines from the 1990s. Preceded by ID and The Face, Dazed’s founders Jefferson Hack and the photographer Rankin were slightly younger than the punk generation who grew up through DIY culture. Famously ID founder Terry Jones started the magazine as a photocopied zine, that collated “straight-up” images of young Londoners’ street-fashion in the style of August Sander’s typological portraits. Slick and professionalised from its conception Dazed’s aesthetic and remit encapsulates a certain spirit of British cultural production that combined a punk-ish irreverence with Thatcherite entrepreneurialism. The New Labour government cited in the Baader-Meinhof piece had come to power, primarily due to the collapse in confidence in the Conservative party, but under the fanfare of “Cool Britannia” which claimed a resurgence of Britain as a cultural and economic force. This political marketing strategy was so popular that in 1997 the American publication Vanity Fair ran a cover feature declaring that London “swings again”. Featuring photoshoots with singers, actresses and models including Liam Gallagher, Patsy Kensit and Damon Albarn in bright 1960s, Kings Road-esque clothes. Future prime minister Tony Blair was also interviewed for the piece, in more sombre but still relaxed attire, appropriate for one third of the triumvirate of the neoliberal Third Way, represented by Blair, Bill Clinton and Gerhard Schröder. Karl Marx famously corrected Hegel’s view that history repeats itself, with the addendum that the second coming of a world event is as farce not tragedy. In Britain in the 1990s, Generation X proved that history can also be made to return as pastiche.

Proll has noted the influence of the earlier generation of British alternative music and lifestyle magazines on German publications, including Tempo4. However, unlike the British upstarts Tempo was backed by the large publishing house Jahreszeiten-Verlag, and so was less reliant on advertising and had bigger budgets for journalists and commissions. Suitably Tempo’s editorial tone was less frenetic than their British counterparts. Proll was focused on reportage documentary but did work with a young photographer named Wolfgang Tillmans who went on to make his name in London through the club scene and fashion world, eventually becoming the first photographer to win the prestigious Turner Prize. The September 1993 issue of Tempo includes a spread of photos by Tillmans from gay club nights in Hamburg, and features an interview with Felix Ensslin, Gudrun Ensslin’s son. Photographed by the Magnum represented photographer Thomas Höpker, smoking in a New York café talking about his experience as a child of the RAF, interviewed by Astrid Proll. How to trace German history from the fractured violence of the RAF to the economic and cultural confidence of re-unified Germany of the 1990s? It’s via Proll.

In the second half of the twentieth century magazine publishing played a significant role in connecting and producing both mass and counterculture. It was a media designed for widespread distribution, affordable but not as disposable as a newspaper. Neither day-by-day nor long-term in their scheduling, magazines formed communities of interests and contained multiple temporalities within their perfect binds. The era in which Proll was at Tempo, and then latterly with The Independent daily newspaper, saw the arrival of digital printing technology and the internet, changing the way media was produced and ultimately the way it was consumed. At Tempo in the early 1990s the publication was still overseen by an office manager; the bodies of the employees were required in the office to physically pull together the issue. Proll says that digitisation came quicker to the British publications, staff were trained to use the new technologies, physical labour slimlined.5 Today, the ubiquity of digital and social media foregrounds user-generated content, making it possible, even recommended, for every individual to be their own publisher and subject. This collapse of labour into representation, and the foreshortening of processes of distribution, has fundamentally changed our relationships to image-production. Without the mediating structure of the mass press events are either made immediate and unbearably close or instantly forgotten. The famous statement by Walker Evans, that “America is really the natural home of photography if photography is thought of without its operators.”6 is now more generally and universally applicable.

One photograph from Paris shows Proll shooting from the Canon Dial into a mirror, the camera itself is central to the image, she is in profile, concentrated, and behind her brother Thorwald Proll and Peter Brosch are out of focus and in conversation. Here Proll is both photographer and photographic subject. Her life and work straddles and synthesises this division, from photography student, to surveilled criminal, the focus of intense media attention, filmmaker, picture-editor, curator and exhibiting artist. Today, we meet her possessing all those identities, and as a representative of all of those categories. In these photos in Paris, she was only just becoming some of those things. These are not photographs of some of the most notorious European terrorists of the twentieth century, they are photos of people who became these historic figures. No future CEO is a captain of industry in their high school yearbook photo, only Kings and Queens are born into complete representational bodies and there was no royalty in 1960s Germany. Outside of the frames of these images is a fifty-year history of distribution and the formation of meaning and value.

The protests on the streets of Paris in 1968 hold a mythic position in the history of left-wing activism but as an event it was time limited. Infamously, May ’68 was over by June. Proll, Baader, Ensslin and their friends weren’t there. They arrived in the autumn, there had been enough to do in Germany that spring. The German Autumn occupies an equivalent space in the leftist imaginary, but Proll, Baader and Ensslin weren’t present there either. Baader and Ensslin were already dead and Proll was in London. The killings of Siegfried Buback, Jürgen Ponto and Hanns Martin Schleyer were carried out by a later “generation” of the RAF, contingent on the politics and decisions on the first group but separated by time and geography. The history of the RAF is often written as a cultural theory. Regarding Terror: The RAF Exhibition at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin (2005) specifically over-inscribed the story of the RAF as a media sensation, producing two exhibition catalogues one with artist pages and critical responses, and one that was a facsimile of the all the German reportage on the RAF the researchers could gather. In this dense chronological document, there is no alternative path from the Spring of ’68 to the Autumn of ’77, but the story of Proll— who did not feature in the KW exhibition or publication— tells us something different.

In his 1972 essay The Metaphor of the Eye, Roland Barthes described Bataille’s metaphorical erotic vocabulary as such: “…the cycle of the avatars it passes through, far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it.”7 Returning to the ambivalent and ambiguous image of Proll and the spoons, the spoons becomes an avatar which stand in place for – even anticipates – two forms of violence. The symbolic or allegorical violence of the potential scoop of the eye, but also the political violence that the photographs precede; the crimes of the RAF and the disciplinary force applied to the perpetrators of these crimes. The Paris photos are amputations or biopsies; cut from the roll of film, slices of a moment of history that occurred just after and just before significant world events, from which violence would unfurl. The task of the historian is to mark out the patterns left by everything that escapes and everything that returns to these images. Which are themselves separated by the missing half-frame negatives, irrevocably split, and cleaved open.

1Darwish, Mahmoud, Eleven Stars over Andalusia in Grand Street, Oblivion, No. 48, Winter, 1994, pp. 100-111

2 Jefferies, Phil, Friends of Astrid, in Peace News, For Nonviolent Revolution, No.2088, January 26, 1979, p.6

3 Grove, Izzy, Baader-Meinhof Gang’ Revolutionary Fiction &/Or Friction Romance in Dazed and Confused, Issue 48, November 1998, p.84

4 Proll, Astrid in conversation with the author, July 30, 2023

5 Proll, Astrid in conversation with the author, May 2, 2023

6 Evans, Walker https://photohelios-team.blogspot.com/2009/02/essay-walker-evans.html

7 Barthes, Roland, The Metaphor of the Eye, in Georges Bataille, The Story of the Eye, Penguin: London: 1967, p.119

Alexandra Symons-Sutcliffe is an art historian, writer and curator. Her work focuses on histories of documentary, film, dance, and performance. Currently, she is completing a PhD at Birkbeck University London on British portrait photography from the 1970s and 1980s.

The exhibition in Erfurt will present a set of 13 photographs printed in 2008 for the exhibition MAN SON at Hamburger Kunsthalle together with various research material. The unique, one of a kind silver-gelatin vintage press prints from the archive of Der Stern Magazine will be on view at this year’s Art Cologne, Sector Collaborations, together with works of the same period by artists Sine Hansen (1942 – 2009) and Jobst Meyer (1940-2017).

→MAN SON, Hamburger Kunsthalle, 2009

Astrid Proll has previously screened her film Der Zug aus Leipzig, 1988 at EXILE Berlin in 2009.