EXILE is pleased to participate for the fourth time in Artissima, Turin presenting, in collaboration with Karsten Schubert Gallery, London, a solo presentation of works from Tess Jaray’s 1988 seminal solo exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

Tess Jaray’s Expressiveness

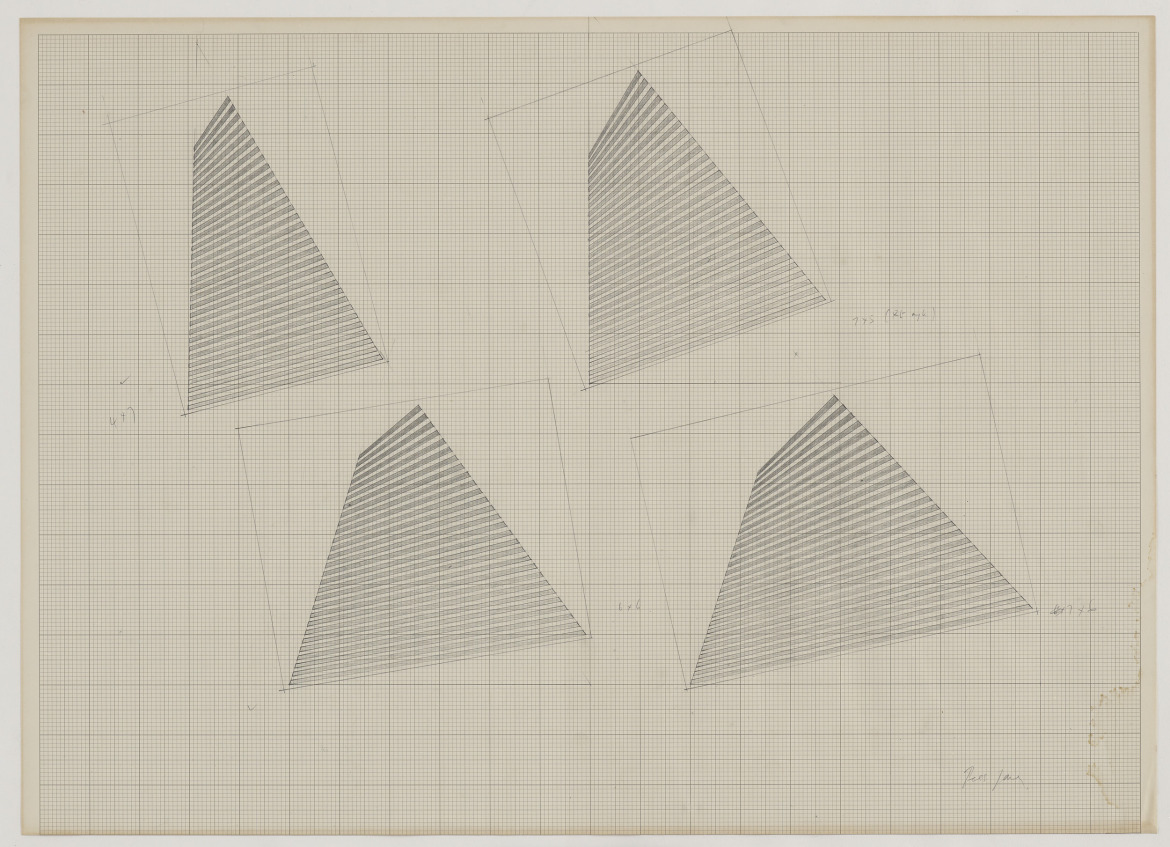

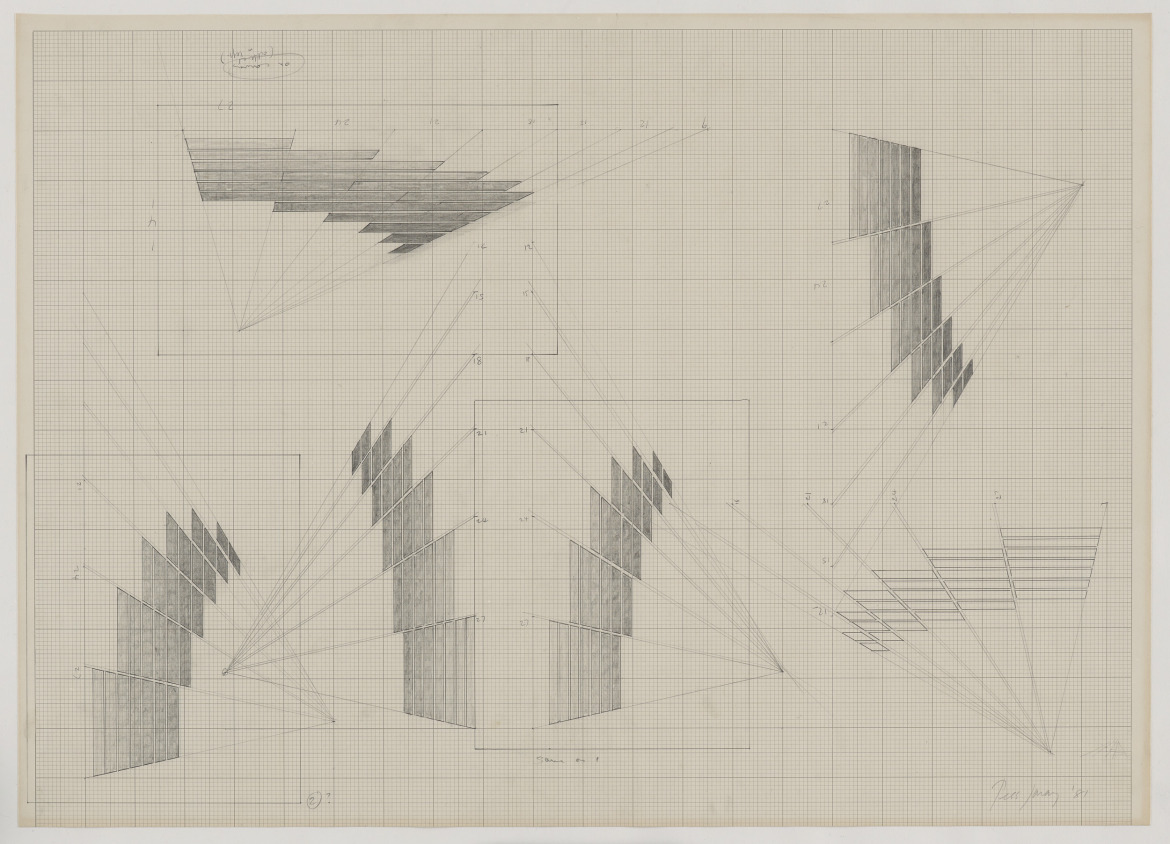

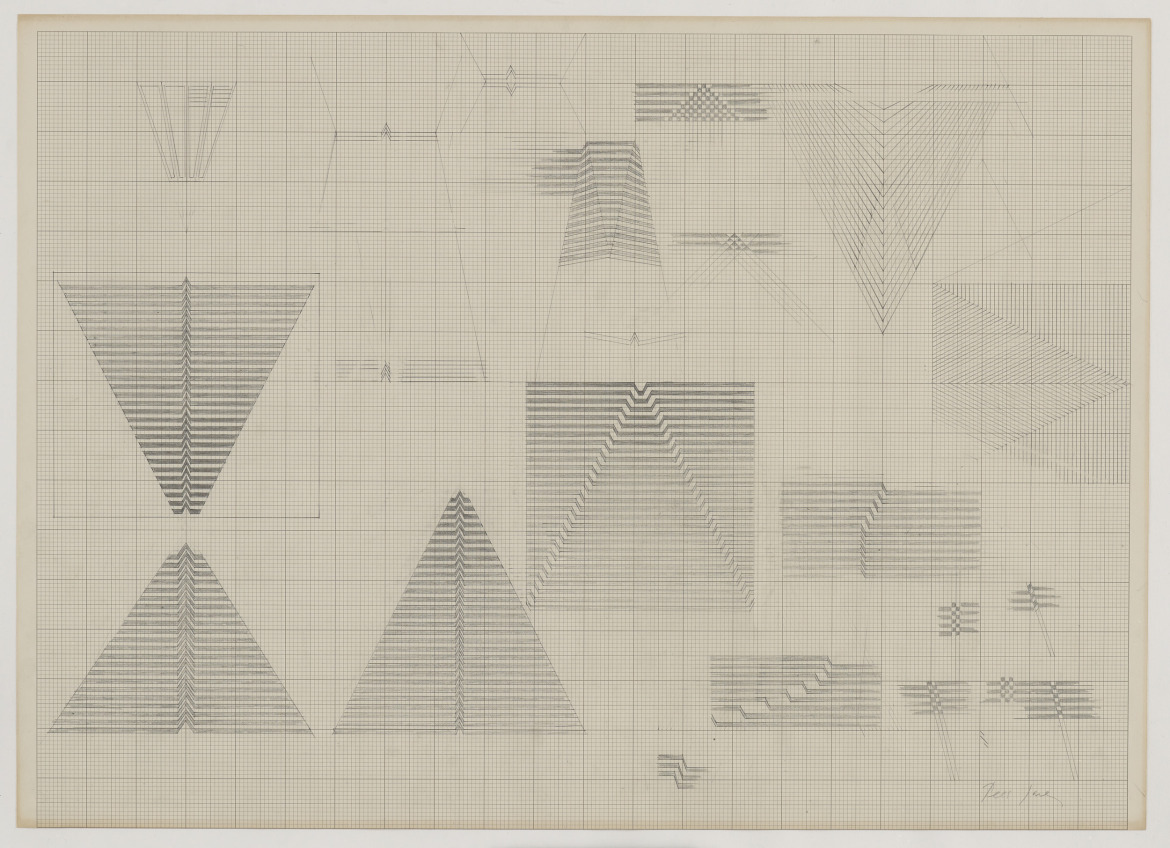

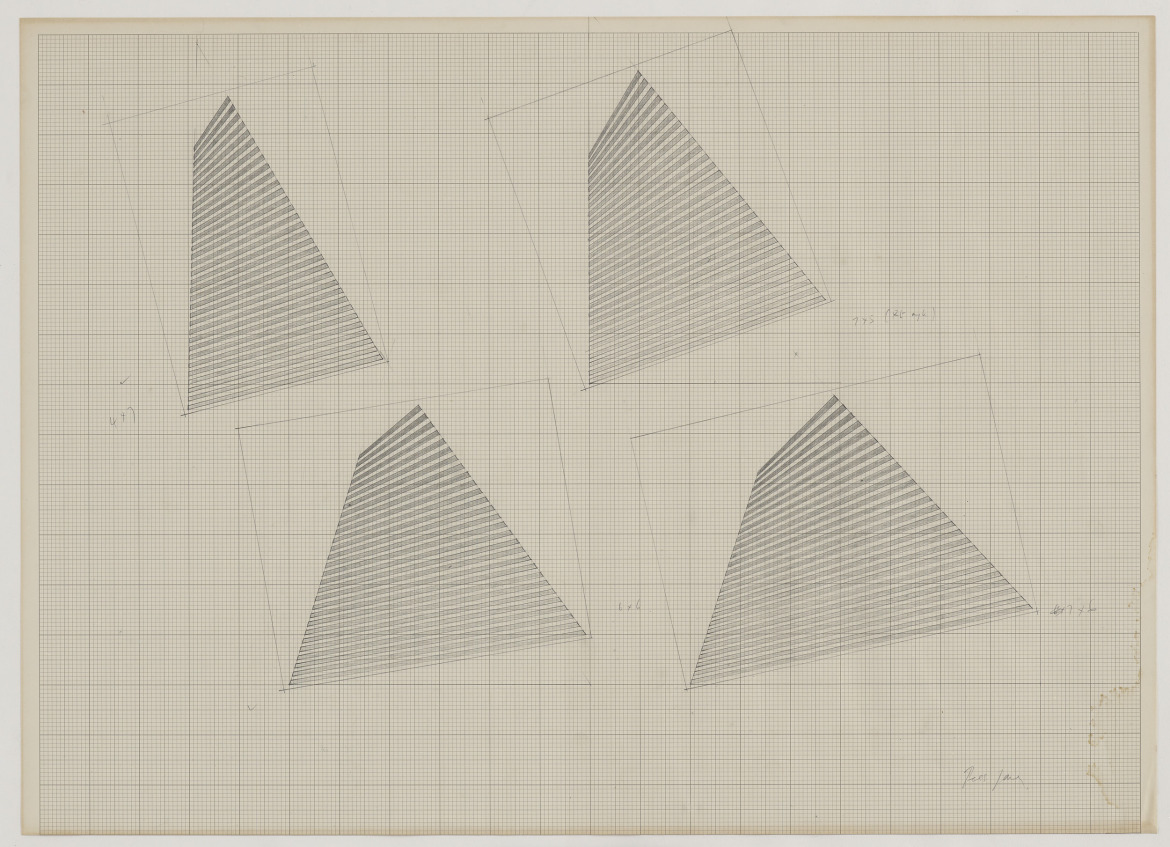

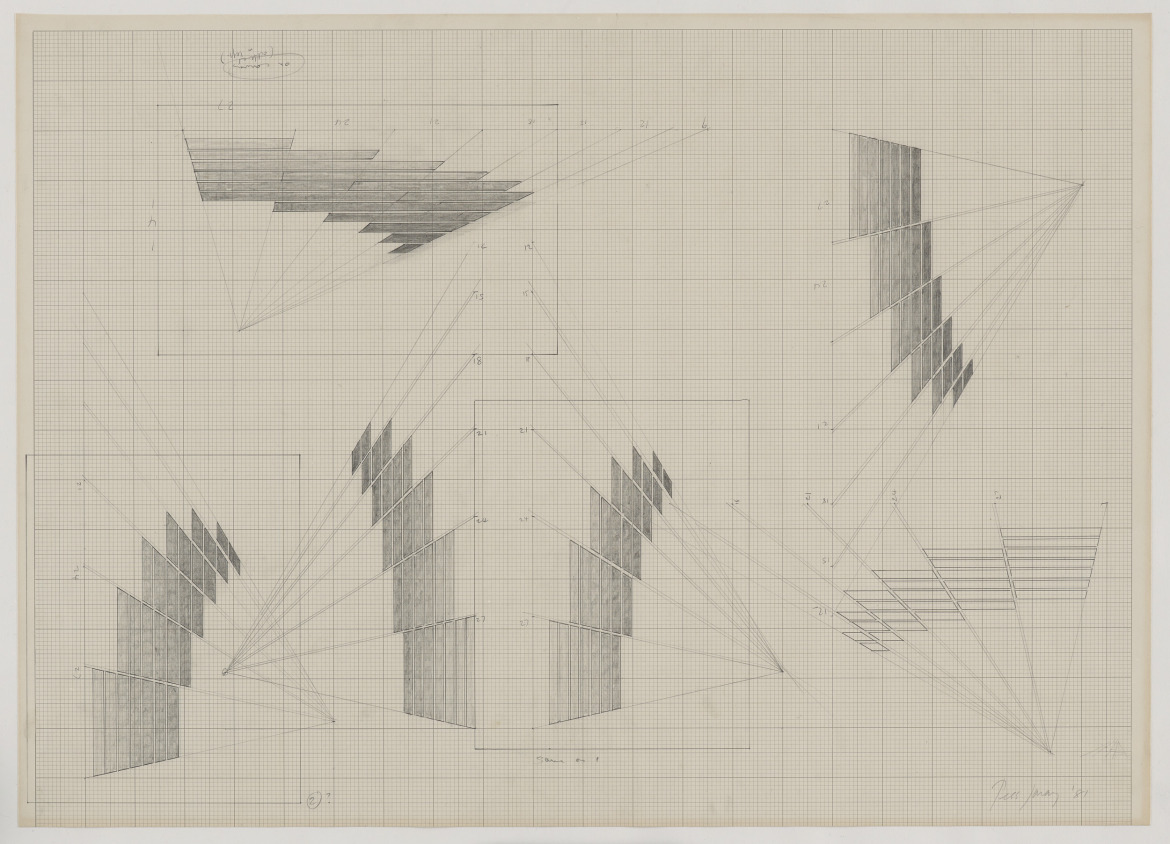

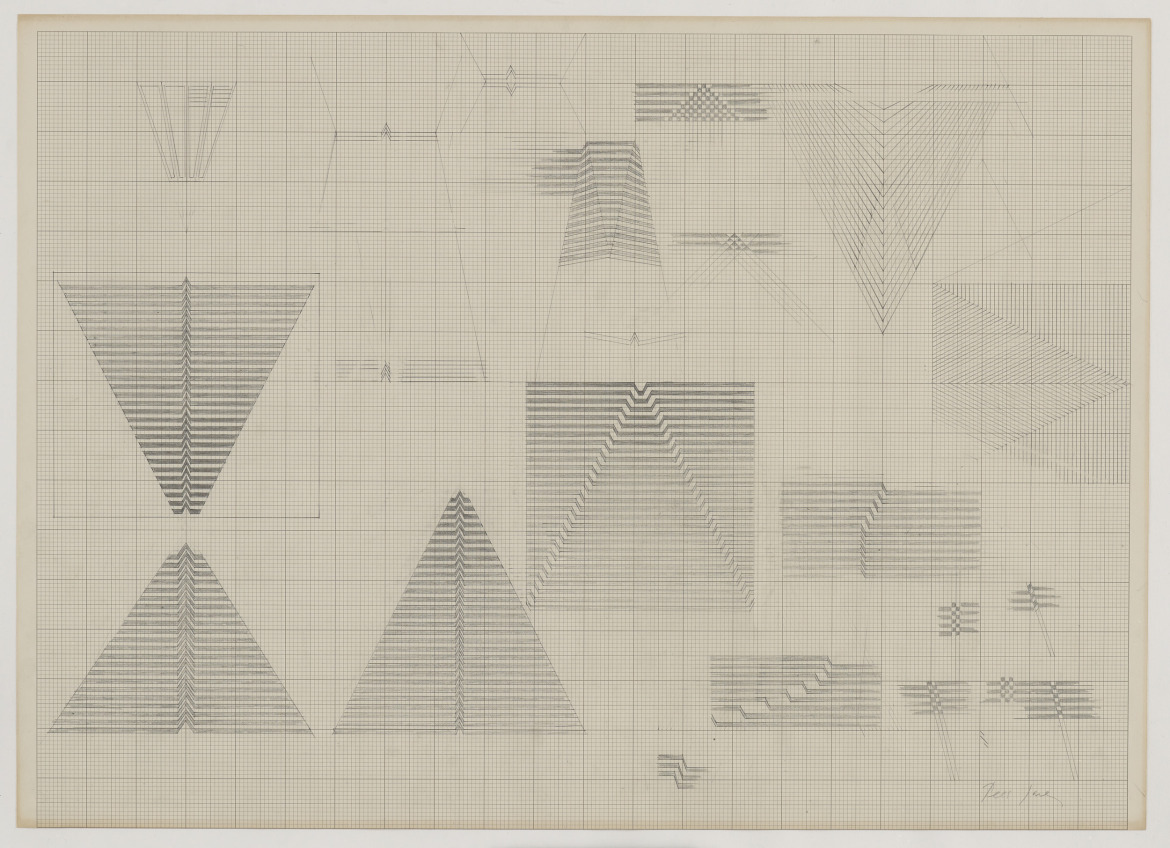

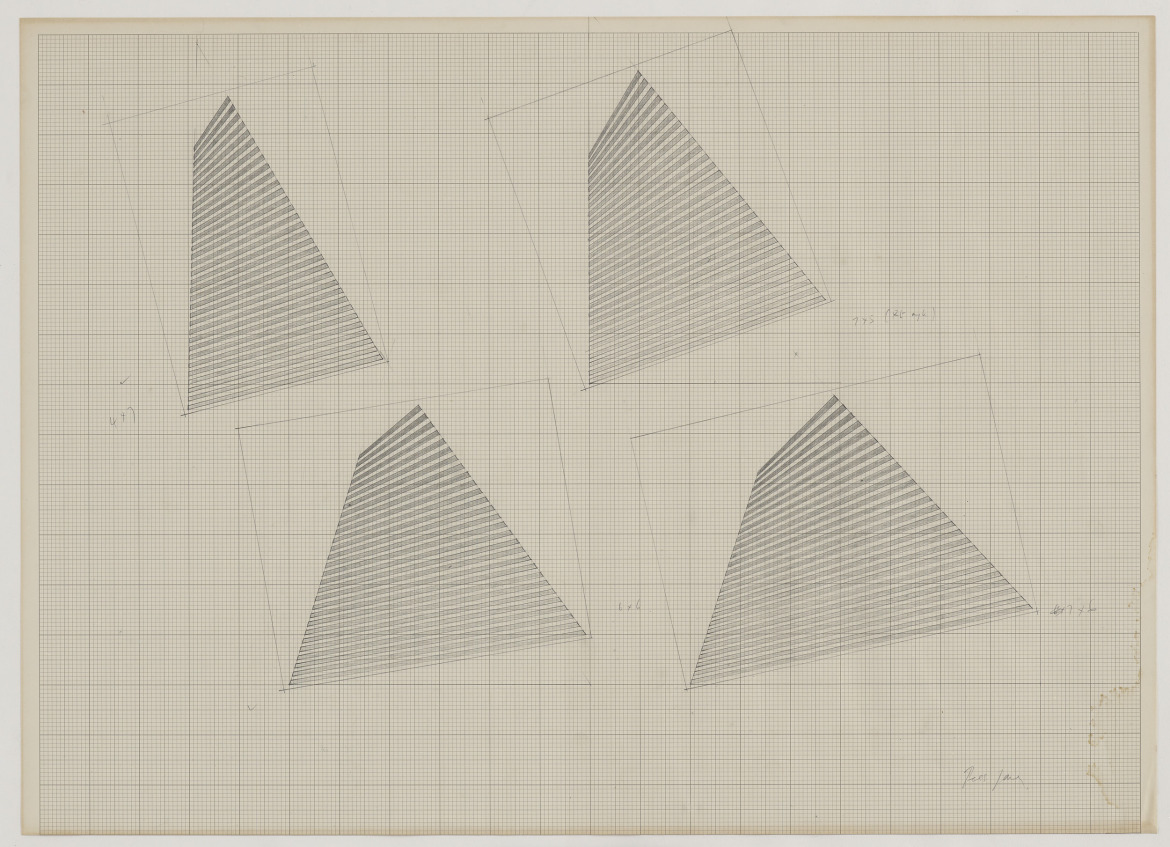

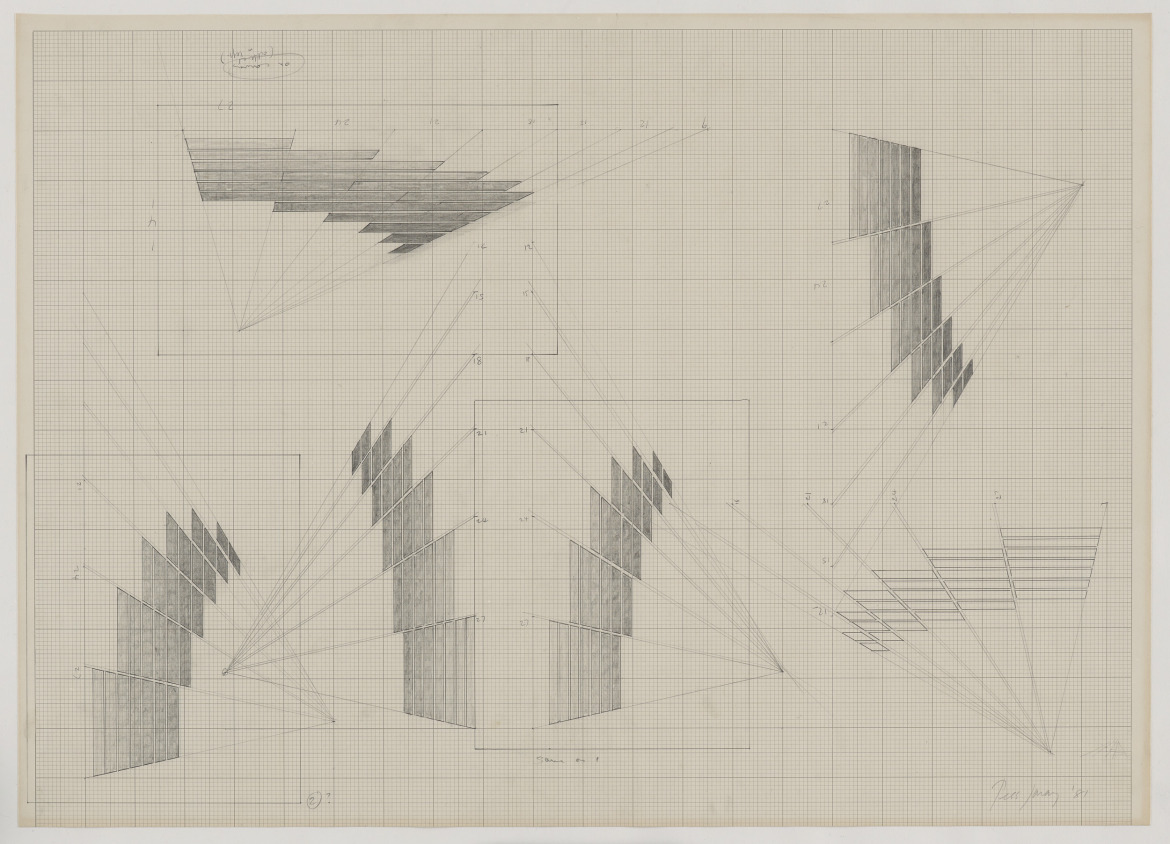

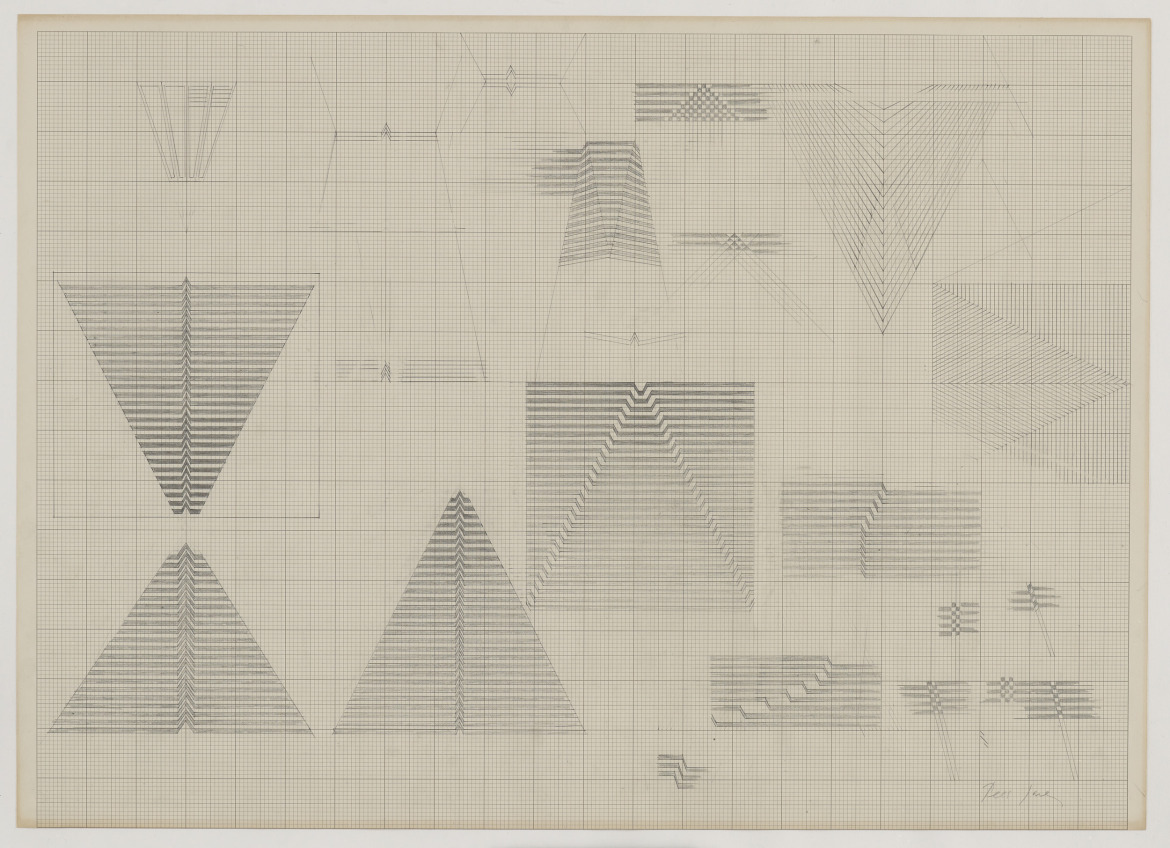

The paintings and drawings brought together in this presentation mark a retrospect to Tess Jaray’s exhibition “Tess Jaray: Paintings and Drawings from the Eighties” at Serpentine Gallery in late spring of 1988. Within the painter’s six decades long career of sustained artistic achievement, the works from the Serpentine exhibition offer a remarkable insight into the significance of Jaray’s painting, not simply with regard to her personal development, but in relation to the momentous answer the artist put forward to the challenges of modern painting in the 1980s.

In March 1968, twenty years before the Serpentine exhibition, a critic writing for the recently founded Artforum reported to his American audience on the prevalence of “measured formal arrangements of basic lines and shapes in two dimensions” in British contemporary painting. Rather than being read as “achieved,” he provocatively observed, these paintings conveyed the impression of being what he called “determined.”1 By this he meant a somewhat Cavellian opposition, namely that in contrast with their obtrusively expressionist American counterparts, British paintings appeared mechanical, more like the implementation of a deduced and predetermined design, then the result of an expressive process.2

Against this backdrop, it may be less surprising that the charge against British abstract painting was picked up twenty years later by another critic reviewing Tess Jaray’s Serpentine show. “At first [they] seem outmoded, harking back to the hard-edged patterns that were in high fashion twenty years earlier,” he remarked about her works, adding plainly: “The brisk visitor will not see them.”3 This may be Tess Jaray’s plight put straight: All too hastily, she can be sorted with a school of painting that she is undeniably indebted to, but likewise she certainly cannot be reduced to. The critic must have felt that. “At first” is the phrase crucial to his judgment, and if her proximity to a “determined” aesthetic may be regarded as her plight, painting at the limits of preconception may be regarded as Tess Jaray’s historical artistic achievement: To push the notion of “achieved” expression, borne by her process of persistent drawing distillation, to the very inflection point of preconceived geometrical pattern without collapsing the paintings into it.

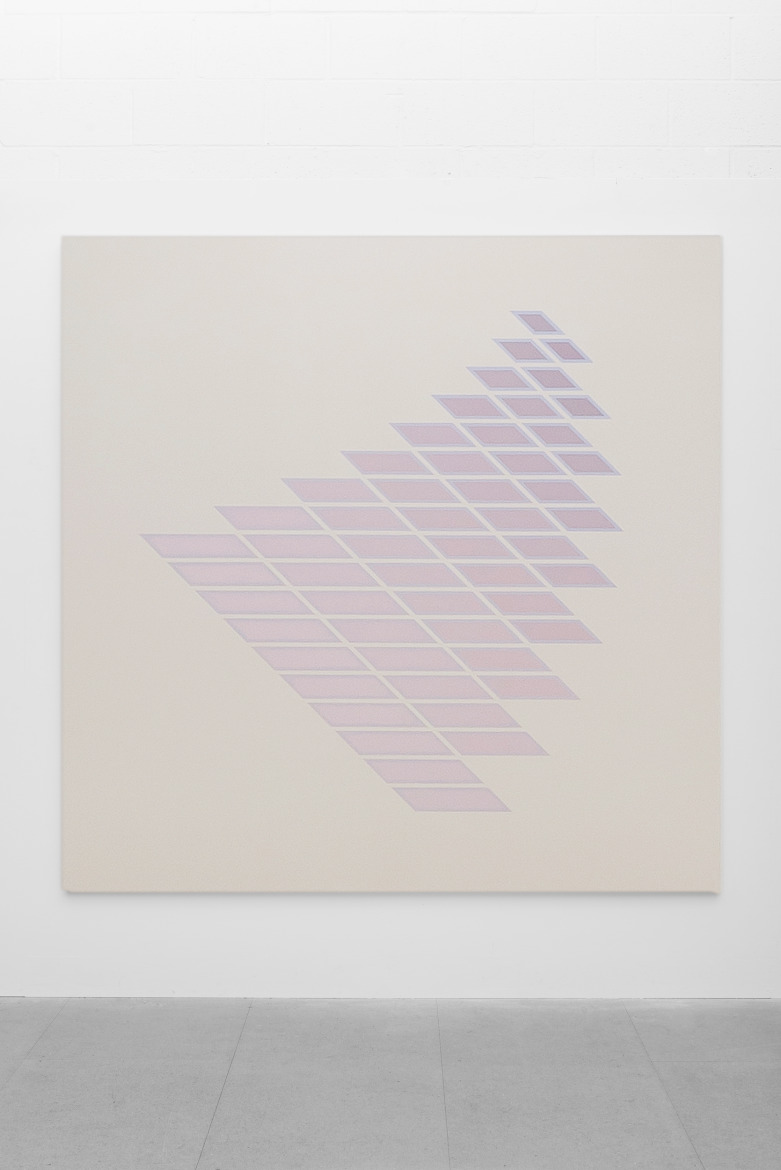

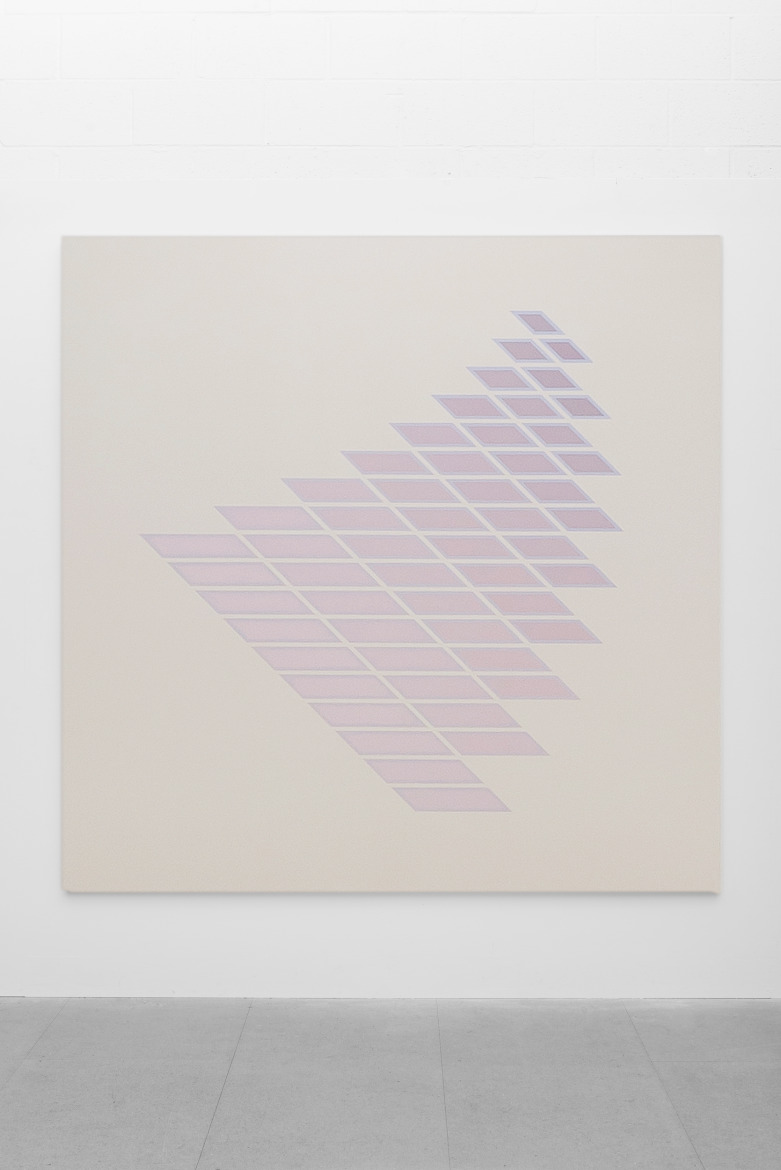

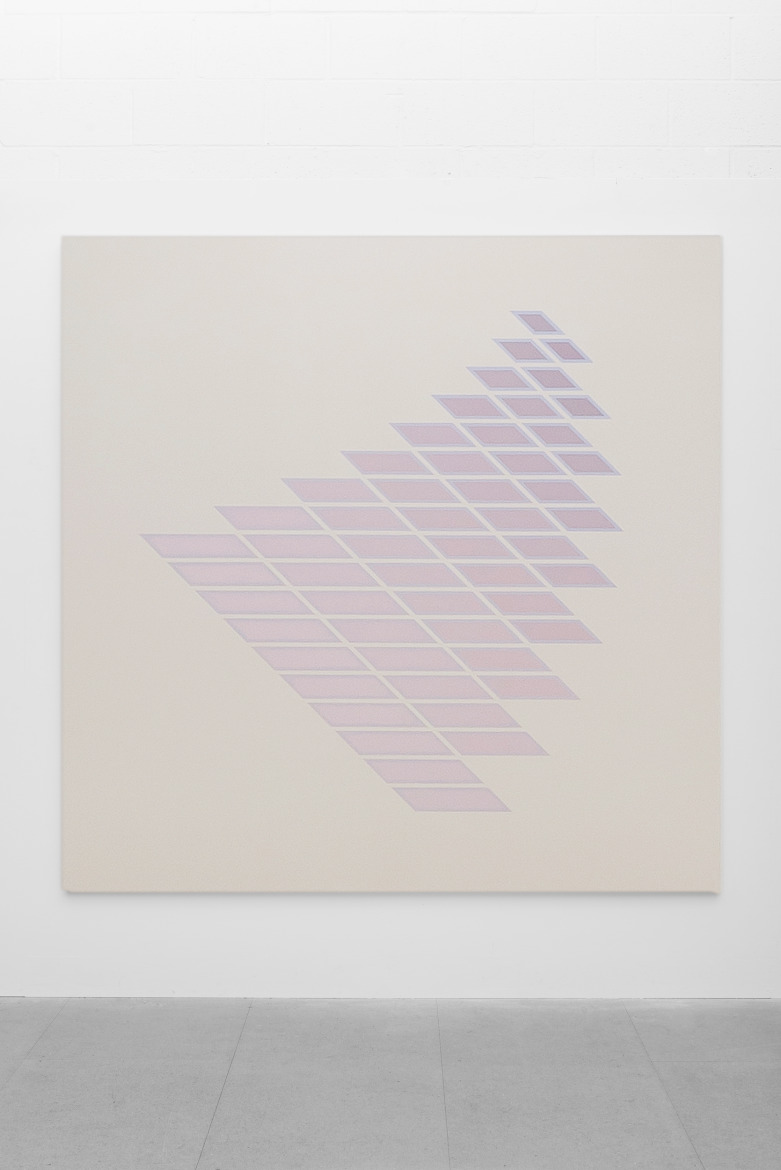

At the core of Tess Jaray’s expressiveness lies a remarkable dedication to tare the thin line between pictorial frontality and depth. Kima, Always now (small), Cast, and Still Point, the four paintings in the presentation, distinguish themselves by an intriguing convergence of pictorial aspects that mark a transition from frontality to depth, and vice versa, to an extent that it becomes virtually impossible to ascribe the overall pictorial effect to either. Take, for instance, Cast, where pairs of parallel bars appear quite frontally at the lower right, but rather staggered and foreshortened in the midsection of the painting, as if we were looking upon it from a higher, oblique angle. Or the pattern of Kima, whose tile-like configuration to the left might entice viewers to imagine a horizontal extension into space, whereas the rhombi to the right appear progressively oriented towards the verticality of the canvas edge, hence accentuating a more frontal perception.

Color has a part in this, too. Markedly in Still Point and Always now (small) where the saturation of the hues seems inversely proportional to the spatial indication of the paintings’ compositions. The frontal rectangles have been furnished with less saturated hues, facilitating a “veiled” impression of depth, while the opacity – and with it frontality – increases the further the composition recedes into spatial depth.

Ultimately, since the geometrical compositions don’t form patterns that extend to the edges of the canvases (and potentially beyond), they simultaneously attenuate the possibility of relating them all too readily to the pictures’ margins which would draw attention to the paintings as frontally oriented objects in space. The uniform grounds, however, in which or “on” which Jaray painted the compositions in turn hamper their coordination with a pictorially immanent coherent spatial context. In a brilliant feat of balancing effects of frontality and depth this means, paradoxically, that the “depth floating” compositions nonetheless utilize the paintings’ material edges for creating spatial coherence, hence creating an uneasy, yet intriguing rapport between compositional depth and the frontality of the pictures’ surfaces.

Through this complex engagement with pictorial form Tess Jaray achieves an expressiveness in painting that even though it doesn’t look immediately subjective in style, ultimately directs us back to the painter in front of the canvas, to her intentions, convictions and preferences.

Back in 1968, Kermit Champa, the critic that had introduced the schematic distinction between “achieved” and “determined” art, also named Tess Jaray, thirty-one at the time, as one of the British artists capable “to break out of the strictures of ‘design.’”4 Clearly, instead of appropriating expressivist tropes of gestural trace, impasto, and the indexical registration of artistic process – poignantly denounced by Hal Foster in his admonitory 1983 essay “The Expressive Fallacy”5 – for Jaray in the eighties this meant to work towards a contemplative expressiveness that breaks out of the strictures of “hard-edged patterns” without succumbing to the self-indulgence of neo-expressionism. If there is something to be learned from her painting it should be that sincere expression needn’t be loud and impetuous, and that good art cannot be measured by the persuasion of a “brisk visitor.”

1 Kermit Champa, “Recent British Painting at the Tate,” in: Artforum, vol. 6, no. 7 (March 1968), pp. 33-37, 34.

2 Cf. Stanley Cavell, “Music Discomposed,” in: id., Must we mean what we say? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000 [1969], 180-212.

3 Brian Sewell, “A talent to confuse,” in: Evening Standard, 19 May 1988.

4 Champa 1968, 35.

5 Cf. Hal Foster, “The Expressive Fallacy,” in: Art in America, vol. 71 (January 1983), 80-83, 137.

Text by David Misteli, 2021

Further Information

→Kermit Champa, “Recent British Painting at the Tate,” in: Artforum, vol. 6, no. 7 (March 1968), pp. 33-37

→Brian Sewell, “A talent to confuse,” in: Evening Standard, 19 May 1988. (PDF, 700 kb)

→Serpentine Gallery exhibition

→Silvie Aigner: Starker Auftritt der österreichischen Galerien, Parnass, Nov 9, 2021