Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, Installation view, EXILE

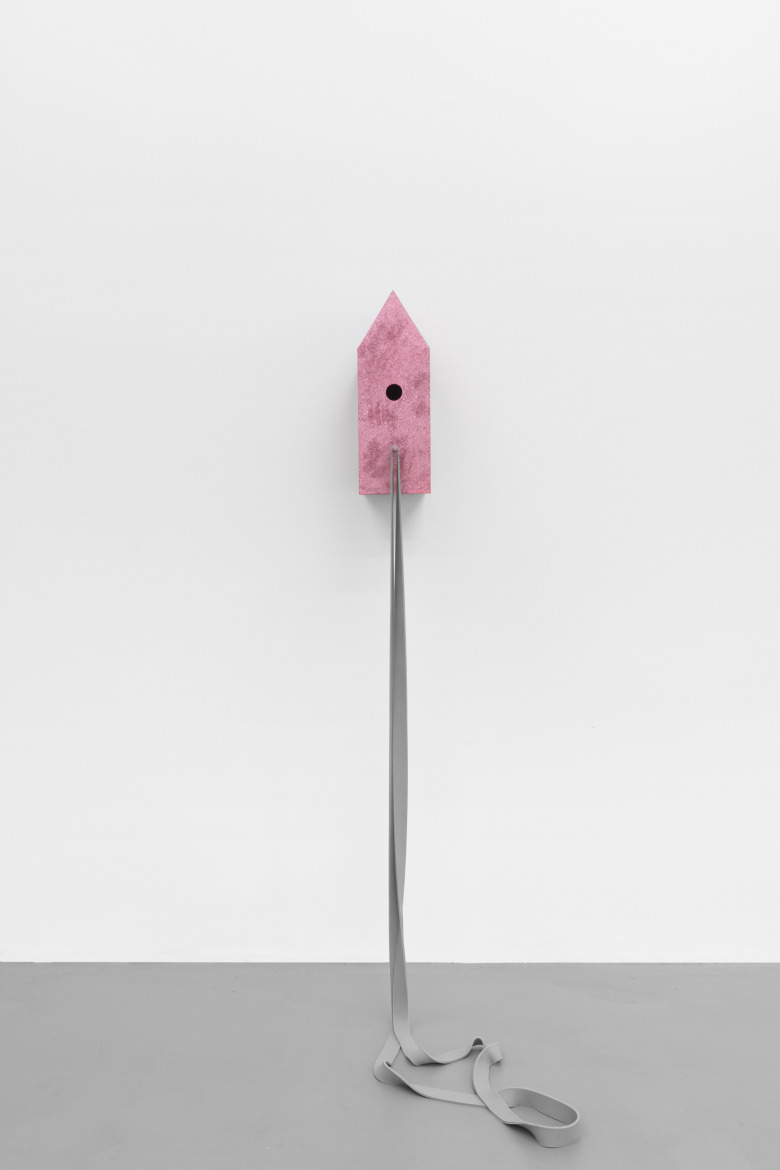

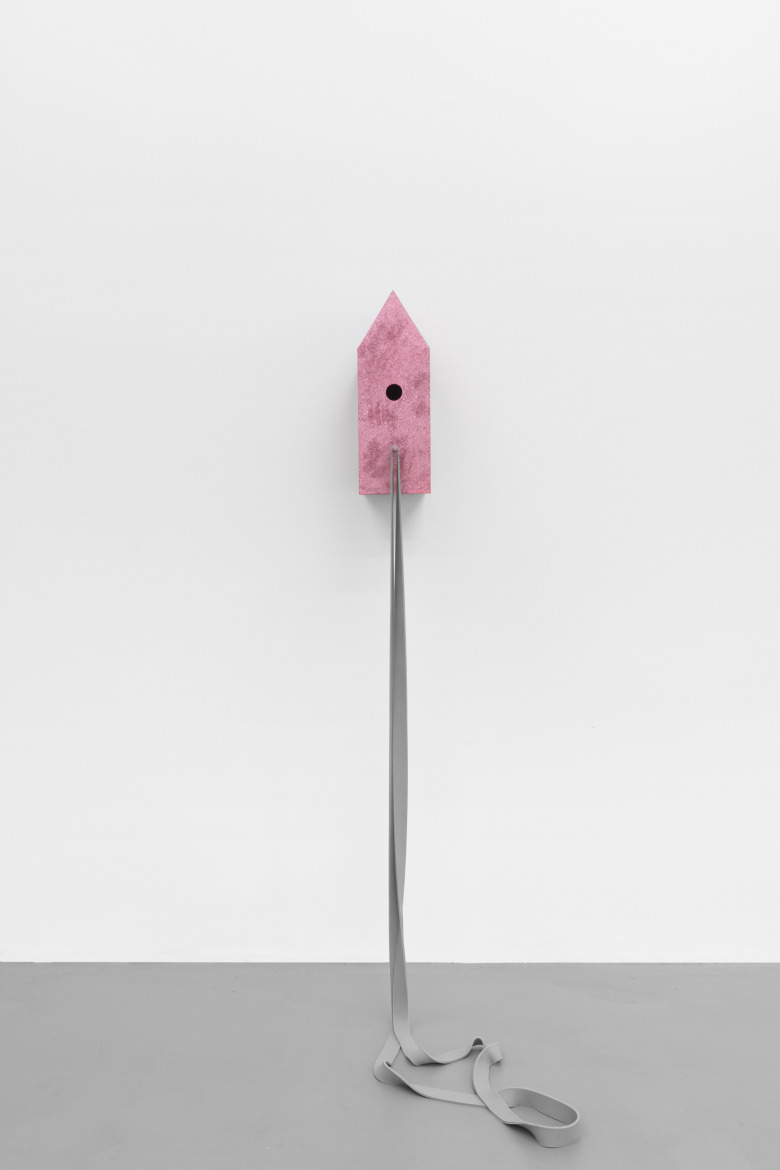

Kerstin von Gabain, Shelter for beasts (noire), 2021. Wood, oil paint, latex, 265 x 30 x 60 cm

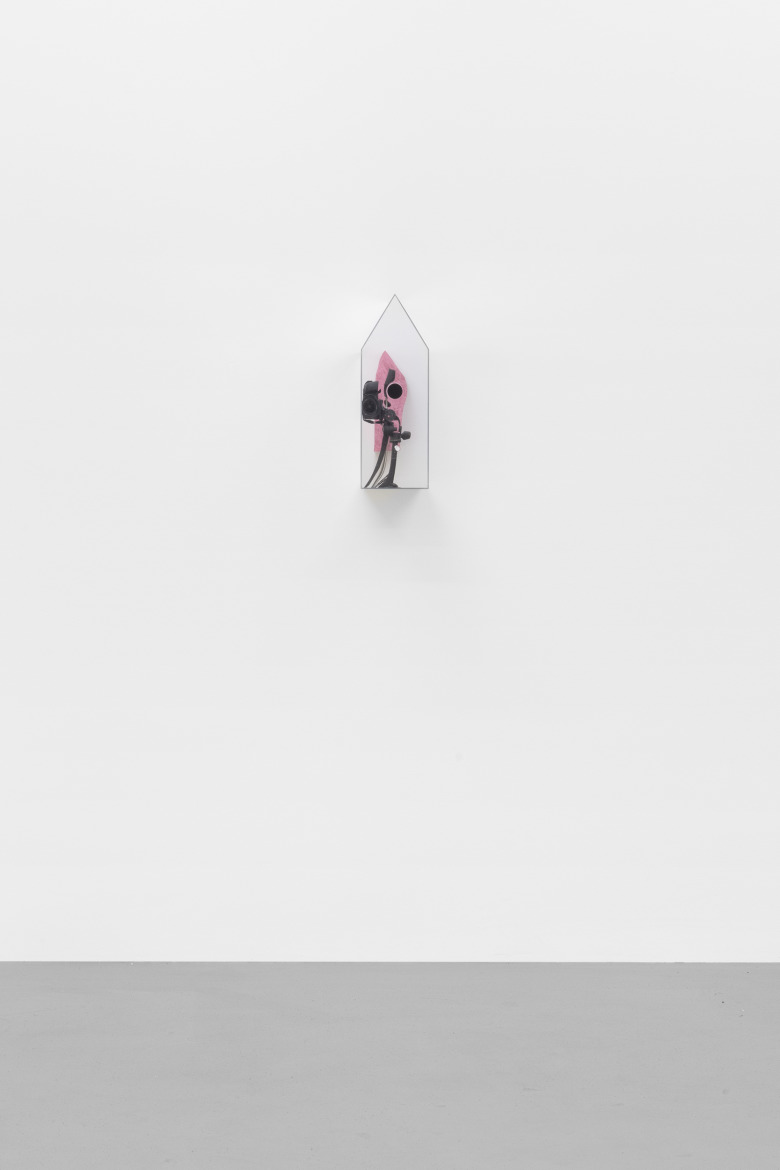

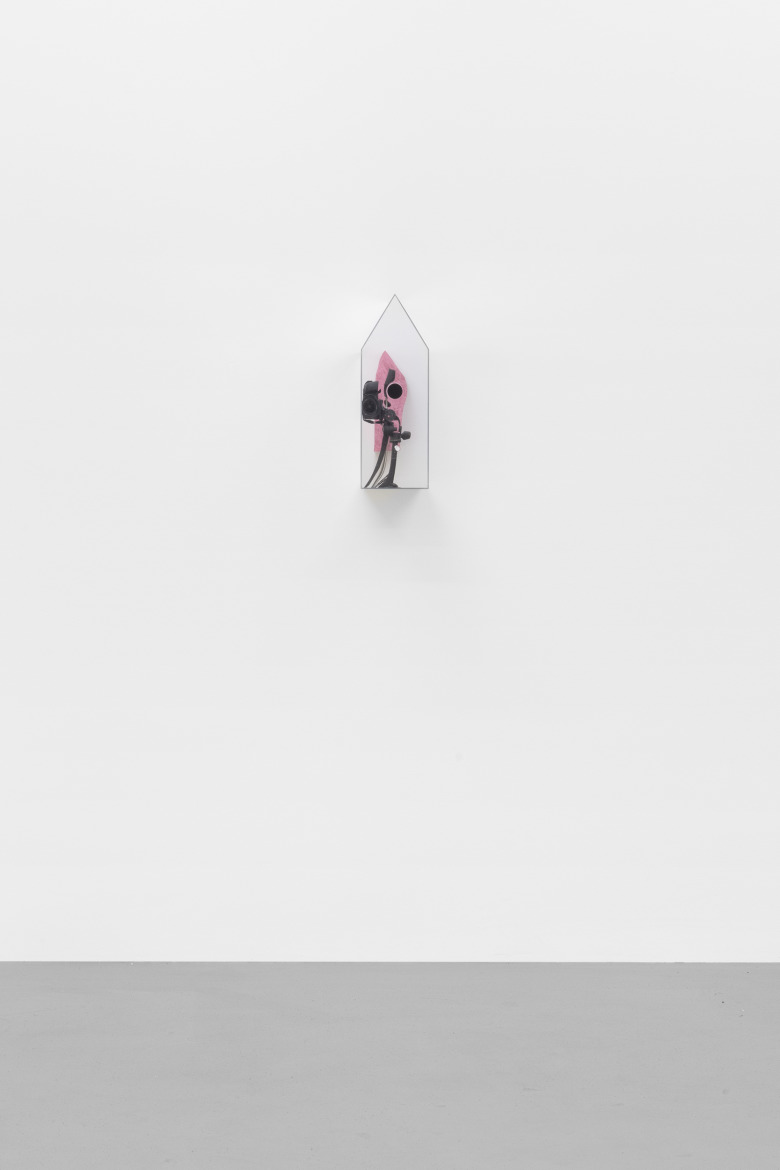

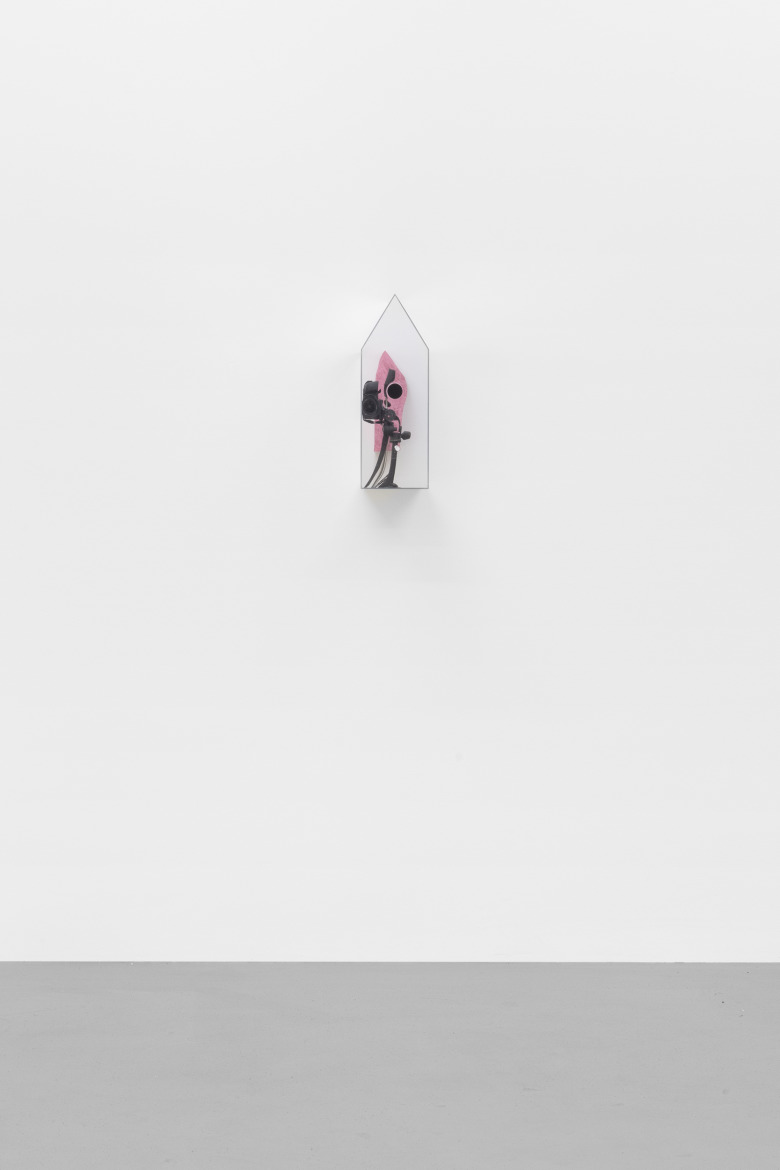

Kerstin von Gabain, Shelter for beasts (Spiegel), 2021, acrylic glass, 42 x 15 x 30 cm

Kerstin von Gabain: Stump (Glitzer), 2018, wax, glitter, guache, wood, 23 x 33 x 12 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, Installation view, EXILE

Kerstin von Gabain, EXILE, 2021, wood, cardboard and silicone, 8 x 13 x 25 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, Branches, 2021, wax, silicone, 7 x 11 x 18 cm

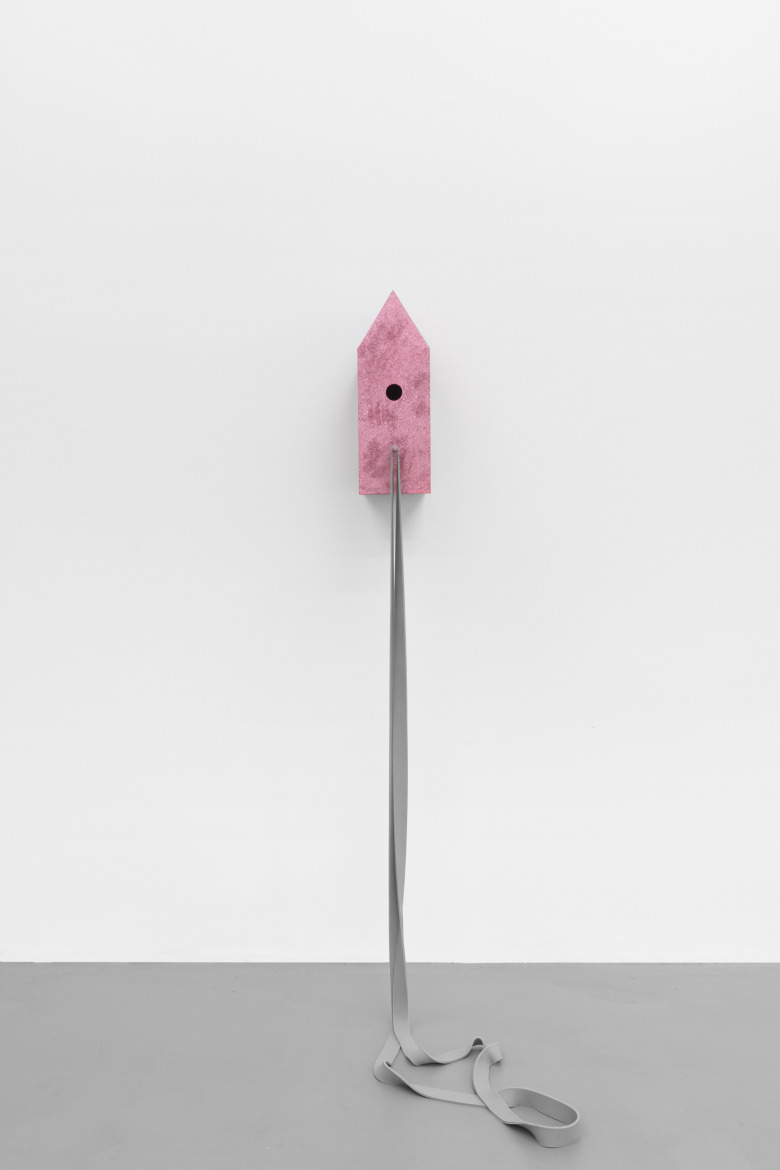

Kerstin von Gabain, Shelter for beasts (Urhaus), 2020/21, Cardboard, oil paint, glitter, silicone, 233 x 31 x 12 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, Shelter for beasts (Spiegel), 2021, acrylic glass, 42 x 15 x 30 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, Installation view, EXILE

Kerstin von Gabain, Feldbett, 2021, textile, wood, oil paint, 34 x 13 x 13 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, Installation view, EXILE

Kerstin von Gabain, Shell, 2021, aluminum, 8 x 14 x 21 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, Installation view, EXILE

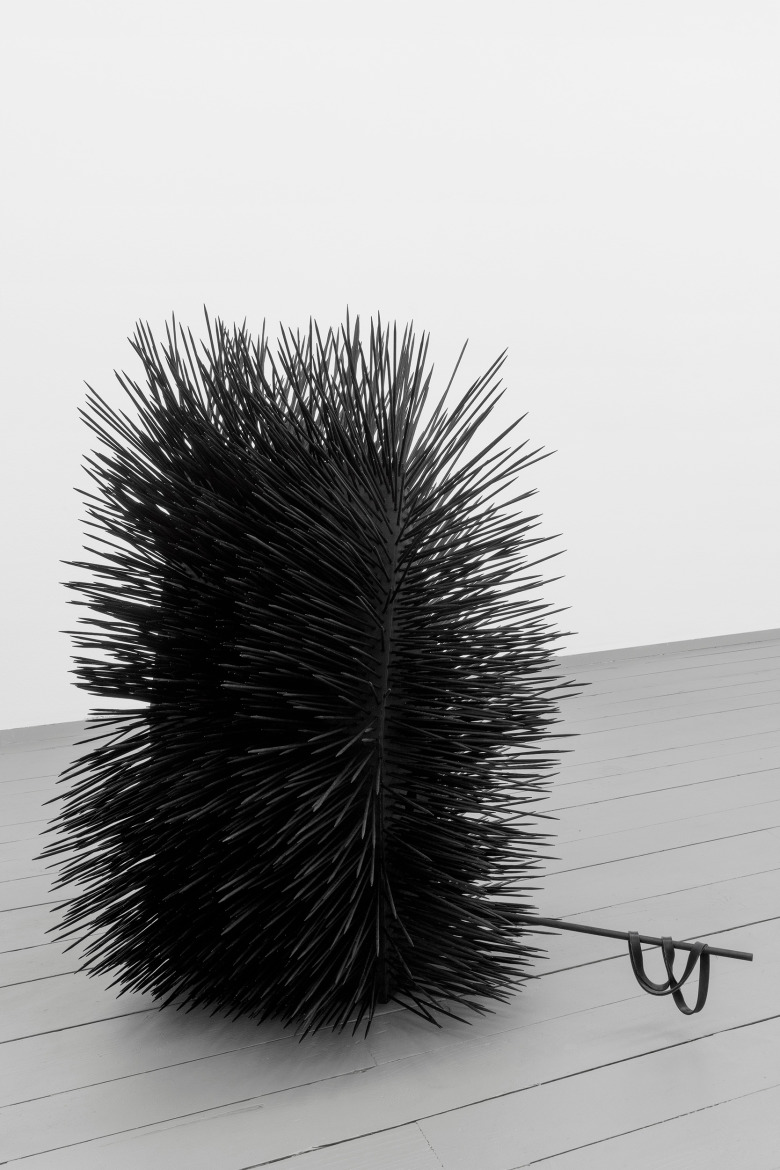

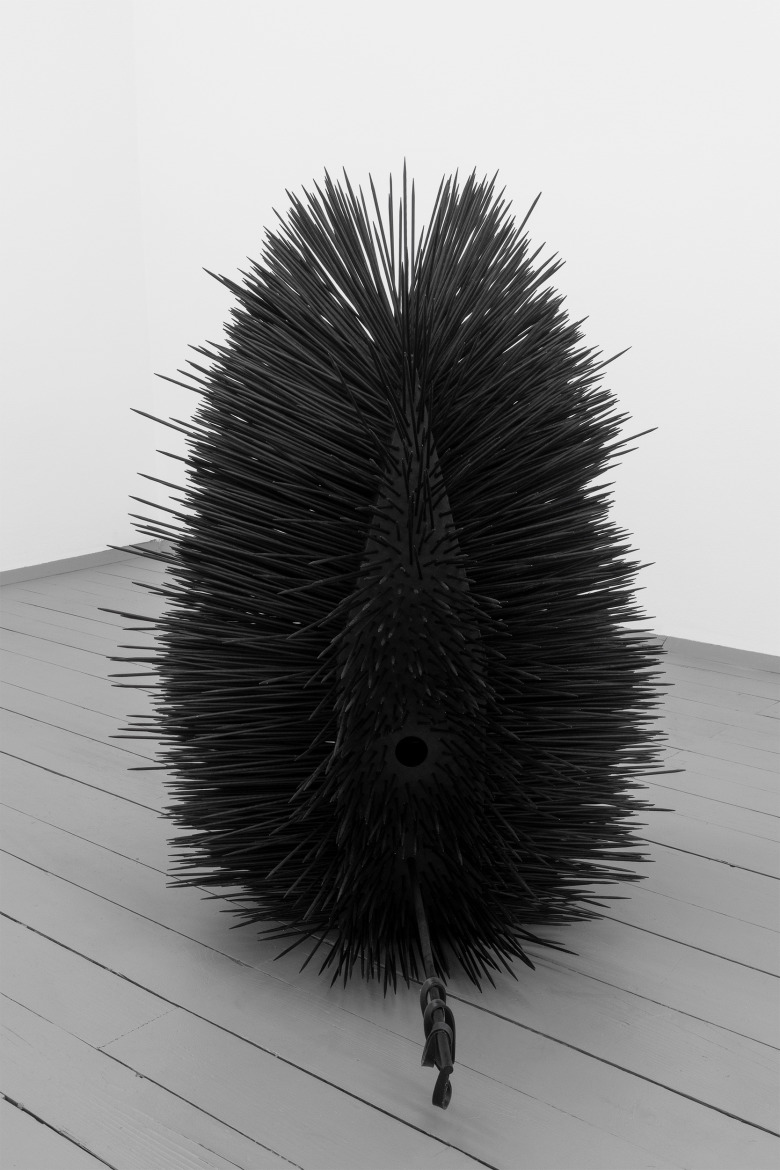

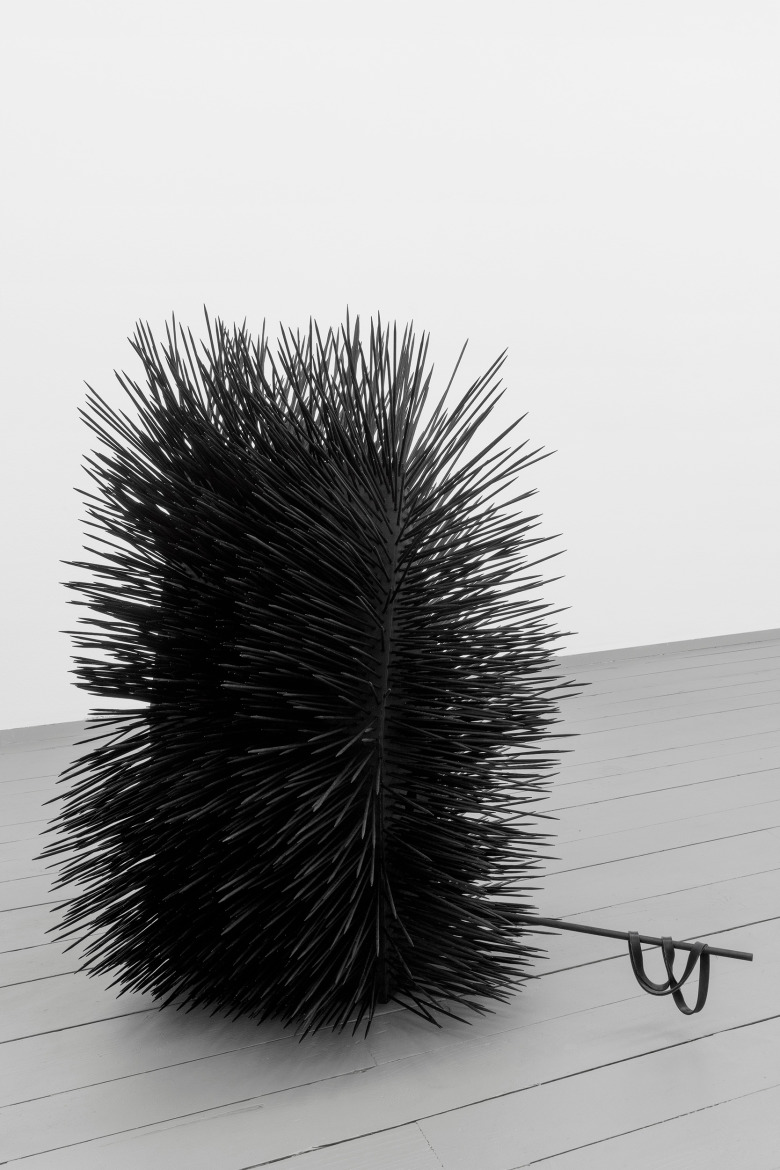

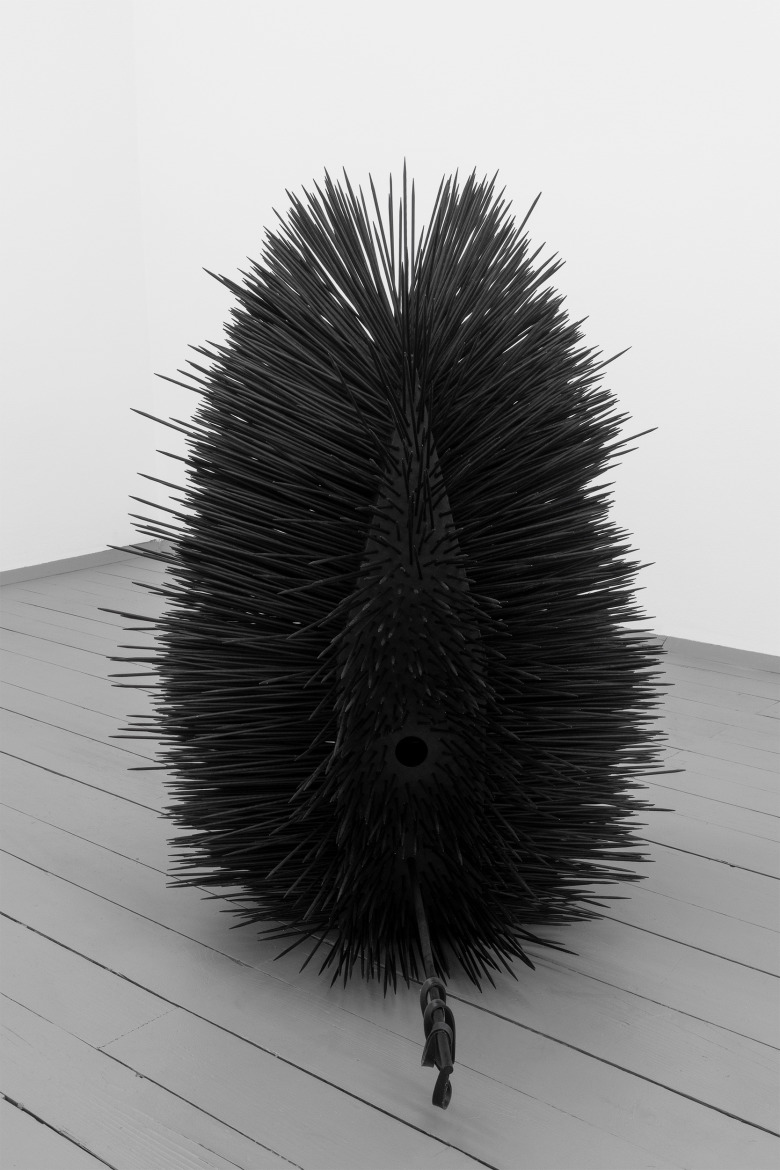

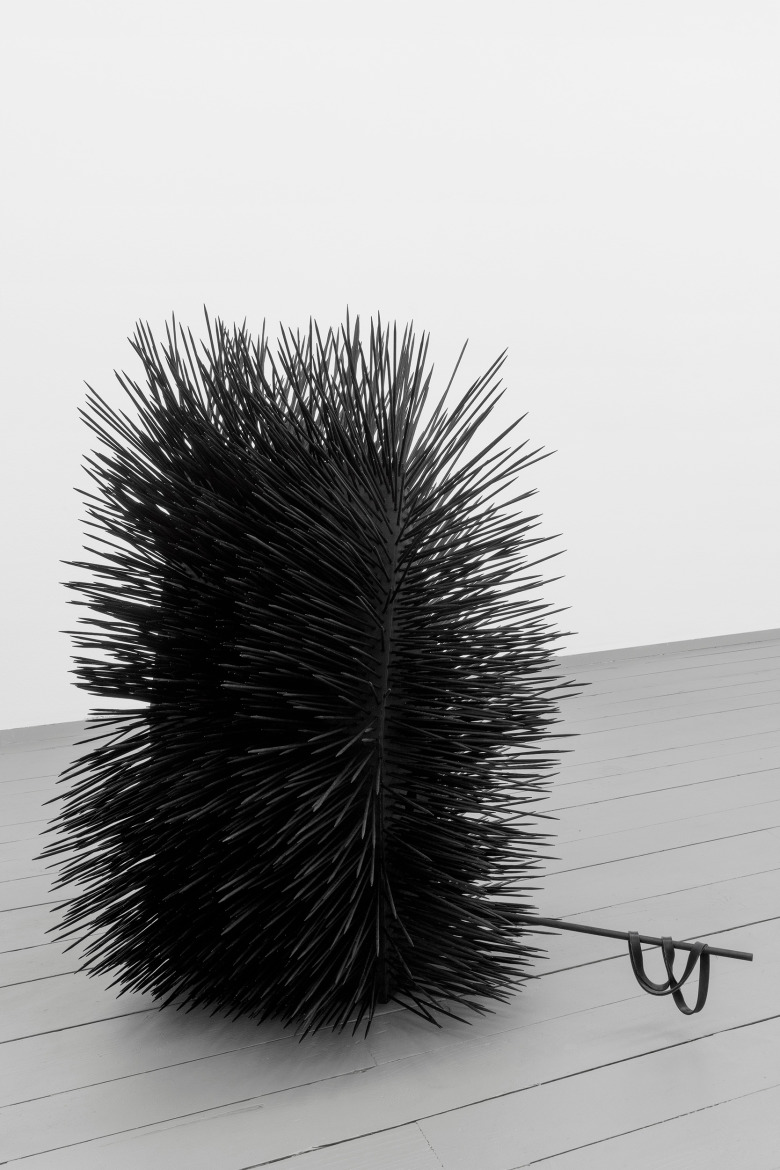

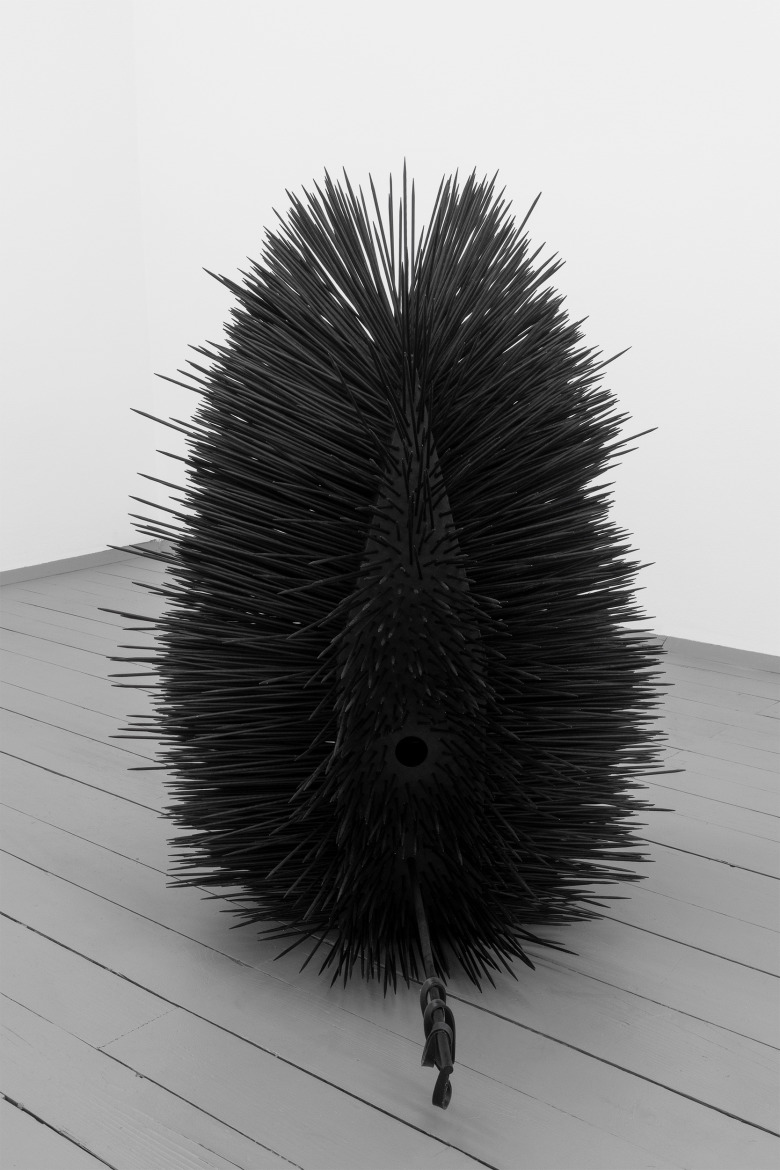

Kerstin von Gabain, Shelter for beasts, 2021, wood, oil paint, silicone, 80 x 60 x 77 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, Shelter for beasts, 2021, wood, oil paint, silicone, 80 x 60 x 77 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, digital print on acrylic, 104 x 104 cm

Kerstin von Gabain, I’ll see you when I see you, 2021, digital print on acrylic, 104 x 104 cm

In lieu of an exhibition text, the mating call of the last male Kaua’i ‘ō’ō, recorded in 1987 for Cornell Lab of Ornithology played at random within the exhibition. To listen to his sound while browsing through the exhibition images click →here.

The Kaua’i ‘ō’ō or ‘ō’ō’ā’ā (Moho braccatus) was a member of the extinct genus of the ‘ō’ōs (Moho) within the extinct family Mohoidae from the islands of Hawai’i. The last male Kaua’i ‘ō’ō was recorded singing a mating call to his female life-partner presumed to have died in a previous Hurricane. The last of his species, he died in 1987. Subsequently, the species was declared extinct.

Exhibition text published on the final days of the exhibition:

Final Call – Kerstin von Gabain’s first solo exhibition at EXILE is about to come to a close. Without the opportunity to experience the exhibition spatially we will rely on memory and story-telling. This text aims to put the exhibition, which deliberately offered neither text nor explanation during the run of the exhibition, into perspective, as not to allow for the experience to full fade.

I’ll see you when I see you, the poignant title of the exhibition is a quote by professional tennis player Naomi Osaka, taken from the press conference following her enforced withdrawal at this year’s French Open tournament. Citing mental health issues, Osaka withdrew not from the sport, but from the press communication that comes as part of the obligations of her chosen profession. In the context of the exhibition, von Gabain pays homage to Osaka speaking out about mental health issues and extends Osaka’s quote to general questions of professional expectancy.

By comparing art to professional sports, von Gabain hints at the expectancy of the artist to show her work to a visiting public which in response forms opinions that are supposed to ignite constructive discourse. Though this cyclical process all too often defines rank and status over contend. The differences between professional sport and art become marginal and few options remain except to perform the in professional mantra to advance, to dance you jester, for the never-ending desires of a voyeuristic entertainment industry or to be sashayed away.

On the outside of the gallery the artist replaced the gallery’s corporate identity display signage with a tumblr image of a sickle on a pretty in pink background. Dragged, dropped and rendered from it’s 35 KB ephemerality to a larger than life 500 GB file, the sickle itself, undefined if harvesting or killing tool, evokes neither harm nor help but describes a mood on which to enter the exhibition. Someone is watching and judging you, always.

Inside, at first glance, a safe haven: white walls, clean looks, few repetitive works: predominantly birdhouses: first birdhouse, then another, yet another, a stump in-between. Covered in reflective mirror, in pink glitter or matte black, the birdhouses’ shape and scale are identical and so are their titles: Shelter for beasts. A birdhouse surely is a shelter by one species given to another. Yet does one species consider sheltering what is described as a beast? Do beasts deserve shelter? Who defines who and what is a beast? Isn’t the definition of beast left in the eye of the beholder?

The bird’s landing strip to its shelter, a rounded stick just below the round entrance to each birdhouse, holds in some instances a long rubbery band. Formally almost mundane and more likely industrial, these soft, anti-form, yet precious and incredibly tactile objects hold a somewhat mysterious relationship to the respective shelter. Undefined, if not on a merely formal level, are these (the remains of) the beast reduced to a piece of soft, non-spinal silicone barely held up by the safety and solid geometric construction of the birdhouse alone? Are they the pun in the joke that truly isn’t funny anymore?

At random intervals, a bird song appears. In lieu of an exhibition text, the bird’s captivating call is the exhibition’s metaphor if not explanation. The bird singing is a Kauaʻi ʻōʻō, recorded in 1983 by Cornell University. The bird’s song and story is as beautiful as it is heart-breaking. The recording is of the last know Kauaʻi ʻōʻō, he is the inevitable last of his species and kind, he sings for his already deceased partner, his dramatic call predicts extinction. A disturbing aria about loss and violence.

Left exposed to all elements, two works in the first of the two upstairs spaces, decry forms of violence. An aluminum cast of the artist’s collarbone lays on the floor opposite a miniature of a first world war plank bed. Appearing fragile and unfinished, the miniature thrones on a pedestal elevated above the armor placed on the floor. A real-life cast of the artist’s collarbone and the miniatured war utensil. War but no peace? Shelter but broken?

The exhibition’s final act is another, though floor-based, sheltered beasts. A cute hedgehog of a birdhouse or an aggressive medieval fortress impossible to conquer despite for its tiny entrance. Another rubbery band, reduced to miniature, lays aimlessly, yet casually in front of its shelter.

The exhibition ends as it began. Questions of scale, of shelter, of armor, of loss and relation, of dark phantasy and light glitter. Shelters for beasts. The lonely bird found none. I’ll see you when I see you.

Further information

→Wikipedia: Kaua’i_’ō’ō

→John Green: Anthropocene reviewed. Sept 2019

→Songbird: a virtual moment of extinction in Hawaii

→Cornell Lab of Ornithology

→Kaua’i ‘ō’ō birdsong

FEATURES

→Artmirror

→OFLUXO

→Art Viewer

→Daily Lazy

→Contemporary Art Daily